At no point preceding my viewing of Blade Runner 2049 did I understand the reason anybody would make a Blade Runner sequel. My perspective, after viewing, remains unchanged.

Blade Runner does not have a good story. It barely has a story. It’s a cinematic poem, a mood piece, an aesthetic. Poetry can have a story, of course; poems can have extensive plots. But many many don’t, especially the ones that are popular today. Popular poetry is for sensual moments, emotional transference, for gesture of moment. Enjoy the delicious and unrepentant guilt of having eaten the plums from the icebox. Relate to Rupi Kaur’s gist. Admire Warsaw Shire’s scope. Or appreciate the attention to detail and unflinching warmth of Pam Ayres and that one often tea-toweled poem about being old and wearing purple because you no longer give a shit. Blade Runner is rich with texture and design, layer upon layer of it, because Ridley Scott is an aesthetician who hired aestheticians and they, along with the cast of actors, provided the flesh to top the exceptionally bare bones of “what happens.”

What is a replicant? In Blade Runner, it’s not made clear. Some people in 2017 still talk about them as if they’re robots. They seemed to me to be some sort of basic clone-form venture. But it didn’t matter. A replicant is nothing; it doesn’t exist. It’s a made up sci-fi concept that has no relevant meaning. The designation “replicant” is there to allow the audience to understand desperation. If you are a replicant, you are under suspicion. If you find a replicant, it’s imperative that you destroy “it.” Replicants are effectively treated by their text as spies, people who are undercover “amongst us” and must be caught out with extensive questioning. It was, after all, the Cold War.

In Blade Runner, a man who doesn’t want to do his job is made to do his job. His job is to catch spies. He catches some spies, but falls in love with a deep cover agent who’s become naturalised. They abscond together even though she is dying. Calling them spies actually makes the film’s story seem more exciting and interesting than it is, because a “spy” is a real thing, a contextual word which implies plenty to a viewer. “Replicant” strips that context away, allowing Blade Runner to be dreamy and gestural, but causing its synopsis to be even less suited to subsequent storytelling! There’s nothing left to happen because nothing began to happen in the first place. We all just had a cool dream.

Blade Runner 2049 begins with red and white text on a plain black background. It begins by defining the word “replicant.” They’re clones with fiddled genes. They’re bioroids. (Or bioroids are them. Which really came first? It doesn’t matter any more.)

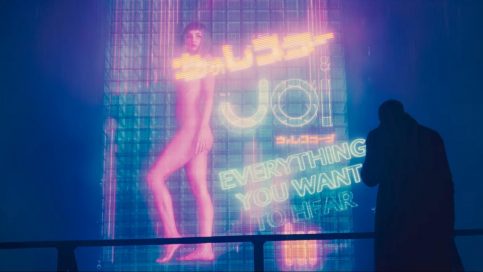

If this film were a miniseries, it would be aesthetically charming. There is certainly craft evident in the making of its backgrounds, it’s costumes. There are frequent allusions to the original’s startling design and wider motifs; there’s a door with tiled patterns that recall the tiles in Deckard’s apartment, here’s your Pris, there’s a holographic advertisement (and another and another and damn, a lot of these are women wearing not so much). We keep getting taken back to Ryan Gosling’ apartment block, as if it was deeply important that Deckard lived in one, which somehow makes it important that this guy does too. There’s your glamorous hotel in tragic disrepair, and here’s that same guy who made all the origami making another piece of origami. Keep it just off screen, I whispered. But they didn’t. He put it right in the centre of the table.

If 2049 were a miniseries that embraced or at least respected its cash-in nature, the strong, earnest work done by the art department would have been far better served, because it would feel like an accomplishment for them to have delicately created a world based on the Blade Runner aesthetic. Television is regarded with less artistic generosity than cinema still. “Art house television” is not really a phrase that sees use. In trying to be “as artistic” as the original Blade Runner, 2049 fails, because Blade Runner created a visual language and 2049 only claims fluency with that language.

As a cinematic sequel, a story that claims by medium–artistically challenging cinema (there is artistic purpose in the editing, the length of all scenes, I think)–to be a legitimate heir, Blade Runner 2049 is peeving and trying because it is far too concerned with “canon” to be atmospherically transcendent and too bonelessly structured for you (or at least me) to feel like sitting there and watching it all at once is a worthwhile venture. Carved up into pieces so its mini-arcs were episodes or at least recognisable as “A” and “B” plots this would feel like a story that needed the viewer to see past its humble nature, rendering all the annoying bits expectable and all of the interesting pieces of the story gemlike and precious.

This is story that inexplicably “continues” Rachel and Deckard’s narrative, killing her before her time (!) and rendering the bulk of the runtime irrelevant to that very story. All of the visual nods and textual callbacks place it firmly and petulantly in the shadow of the original, which by 2017 makes it an absolutely semiotically normal piece of science fiction. The one major motif that wasn’t used was the last one, the vital one, the only one that would have had any real meaning: “time to die.” Roy Batty would weep, if he knew. Roy Batty, the villainous replicant of the original film, who fought to live and fought to own his reality, who faced death with purpose and acuity–he is the replicant who was the miracle! And his self-possession should have been a gift that was passed down to the next cancelled-early, soulless, fake person who did their best to break free of social conditioning and reckon with his responsibility to himself.

It’s very hard to discuss the events of Blade Runner 2049, because it is so itemised that one becomes a relay service rather a reviewer. In gist, a man trained to be passive wanders around doing what he’s told until at the very, very end he awakens to his self-determination. His wanderings are used to allow the audience to see various facts about the world he lives in, such as “you can buy a holographic wife,” “replicants are expected to dehumanise themselves at all times,” “this is a bad world full of misery,” and so forth. “Rich people can do what they like.” The film doesn’t really push any special principle onto the audience, but it does vaguely–purposefully vaguely I think–because I think enforced passivity is the intentional tone of this film. It suggests that in the future the environment is broken and humanity relies on product-services, such as a) holographic wives and b) replicant workers. Oh, and c) child labour. It is allowed to be assumed that this is bad, for the holographic, replicant, and straight-human people who comprise life in LA.

It couldn’t be said that 2049 tries to impose an obvious agenda on its viewers, but it certainly brings many familiar post-human philosophical posers to the table. I don’t feel inclined to pick many of them up, because, frankly, how old do you have to be to have never believed in the emotional personhood of AI in fiction before? I was born the same year as Data from Star Trek, three years after Neuromancer. Watching this film felt like waiting for someone to finish telling me something I already know, and slowly realising the misogyny they’re embedding in the info is corrupting the message I already started nodding to.

Blade Runner 2049 doesn’t effectively grapple with the ethics of slavery or eugenics, or the personhood of created lifeforms. It absolutely doesn’t grapple well with the politics of birth or the ownership cisgender men feel towards either productive wombs or sexually attractive women. It seems particularly cruel, to me, to establish so thoroughly and so pointlessly the motif of slicing a woman across her pelvic flesh, and then to continue to slice other things slowly. To put maiming violence on the screen, and women’s naked bodies, and women’s used bodies, but to pretend that men have bareable shoulders and the rest of their bodies just come cased in fabric. To establish a terribly vulnerable companionship between two women for the pleasure of a man who doesn’t have a need for pleasure, and to immediately set them against each other with extreme prejudice after he’s come and gone. To create sets that are just giant broken naked women in high heels with gaping mouths and the colour orange. To write such a poor script for Robin Wright. To write a script that has a demographic claim that childbirth can prove they are not innately slaves, and cast one of two black adult bit parts as a child salesman. To designate a womb that cannot gestate a fetus as such a failure that it makes Jared Leto murder a baby.

Ryan Gosling did a good-faith job that I found fairly interesting, and Harrison Ford really tried to sadly cry (fascinating). Several actresses did great work with what they were given. Sylvia Hoeks, in particular, gave a terrific performance before she suddenly became an evil kickboxing dominatrix. And there are scenes and sequences that would work in a solid future-punk story. But it is interminably long, for a plot that is no more than “a guy catches some spies. Then he finds out his parents were communists, and has a change of heart.” And it keeps going “BWAUUUUUUUMMMMMMM.” It gave me a headache, and it made me indignant for the women in the story. It ends with Deckard coming in from the cold, except…the guy who put out a hit on him is the king of the world, and the protagonists do not at any point beat him. They’re all gonna be dissected and die, reader. And it will be painful, just like Rachel’s death was. Apparently.

Sequels! What are they for?

By Claire Napier ON

You must be logged in to post a comment Login