The women who screamed and swooned for the 19th Century piano virtuoso Franz Liszt set the pattern for fans in our own time – from The Beatles to Justin Bieber.

The spectacle of young women shrieking, sobbing, and swooning at the sight of their musical idols might seem like a peculiarly modern phenomenon. You might think it first emerged in the 1950s and ‘60s with Elvis and Beatlemania, and was given a new lease of life in our own age where One Directioners and Beliebers battle it out to prove they are the most loyal pop fans on the planet. But the phenomenon is nothing new. And surprisingly, it has its roots not in post-war popular recorded music, but in the classical concert halls of 19th -Century Europe, where an outrageously talented young Hungarian named Franz Liszt overcame a very poor background to become a bona fide ‘celebrity’. (According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word was first used in the way we use it now in the 1830s, as Liszt rose to fame.) The ultimate classical superstar – even more so than his musical hero, the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini – this legendary composer, pianist and pedagogue unleashed what his biographer Dr Oliver Hilmes describes as “a highly infectious strain of Lisztomania that gripped Europe for years at a time”.

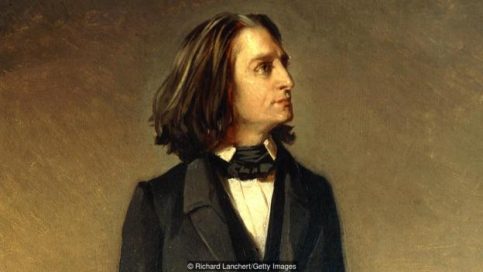

Franz Liszt (1811-1886) was a child prodigy who began casting his spell on audiences in Vienna, Paris and London at a young age, not just for his preternaturally gifted technique and fine musical imagination but also for the distinctive air he cultivated at the piano, tossing his shoulder-length locks and swaying hypnotically over the keyboard as he played. During a period of eight years, he gave around a thousand recitals – “an incredible total,” Hilmes stresses. “In the process, he effectively invented the profession of the international concert pianist. Crowned heads of state paid court to him, women threw themselves at his feet and others lost their reason. The popular press of the time reported at length on Liszt’s concerts and at even greater length on the numerous escapades that fuelled their feverish interest in him.”

Classical music audiences have a reputation for being decorous if not downright prim, but such was Liszt’s broad appeal, says Hilmes, that “there were times when the enthusiasm triggered by his public appearances bordered on delirium, and he became a figure on whom contemporaries projected all manner of erotic fantasies and secret desires. There were women who forgot everything, including their family’s good name and their refined upbringing, to be close to their god. One eyewitness recalled that ‘on one occasion a woman snatched up a half-smoked cigar that Liszt had cast aside and in spite of repeatedly retching she continued to smoke it with feigned delight’. Baronesses and countesses tore at each other’s hair in trying to lay hands on a glass or handkerchief that Liszt had used.”

Screaming, cheering, swooning

‘Lisztomania’ was a term first coined by the 19th Century German poet and Liszt’s contemporary, Heinrich Heine. But such behaviour – or its equivalents – wouldn’t exactly feel out of place in the 21st Century. Dr Ruth Deller, Principal Lecturer in Media and Communication at Sheffield Hallam University and an expert in fan behaviour, points out that “some of the activities that fans engage in today, we can recognise in the fans of Franz Liszt. Those that were reported at the time include his fans’ emotional and physical responses – screaming, cheering, swooning – and their devotion to following him as he performed in different venues. These kinds of activities have long typified fandom and still do.” Deller suggests that the stereotype of the “screaming, swooning female fan” may even have a basis in the contemporary press coverage of Liszt’s concerts.

There is, however, a critical difference between Liszt’s time and the era of Beatlemania and beyond, and that is the ever more sophisticated ‘PR machine’ behind the artists (although Liszt was clearly no slouch when it came to self-publicity.) Deller points out that, these days, when it comes to creating a superstar, talent may be just a small part of the equation. “There are so many factors at play,” she says. “Talent, yes, but also looks, charisma, branding, catchy tunes, marketing: these all play a part. It’s not necessarily predictable: you can throw a lot of money and publicity at an artist and not receive a great return on your investment if there isn’t something there to catch the public imagination. You might call that charisma, presence, the ‘X-factor’, or you might be a little more cynical and call it a well-crafted image with fantastic PR and marketing.”

But Liszt, living and working over a century before mass communication, was indubitably the real deal. “He was the first to perform the whole of the known keyboard repertory from Bach to his contemporary Chopin,” explains Hilmes, “and he did so, moreover, from memory. As a composer and orchestrator, too, he was a revolutionary, writing pioneering works that opened up whole new worlds of expression.” The leading contemporary pianist Kirill Gerstein, who has recently recorded Liszt’s fiendishly difficult Transcendental Etudes, points out that between 1830 and 1850, he invented “pretty much every possible pianistic device that appears in modern piano writing. Composers ever since have used these, or elaborated on the seeds of keyboard ideas that he planted in his works.”

Hungarian rhapsody

Was Liszt unique, then? “The word could have been invented to describe Franz Liszt,” maintains Hilmes. “He was possibly the greatest pianist that has ever lived,” Gerstein agrees: “a composer of revolutionary works that exerted pivotal influence on those that followed – also a great teacher, humanist and possibly the nicest of the great musicians.” Is he conscious of the spirit of Liszt when he plays the music? “It’s a bit like viewing the peak of Everest – out of reach, yet inspiring,” Gerstein admits. “When you play Liszt’s notes on the keyboard, your hands get to trace the outlines of the shapes his hands created. Similarly, the greatness of his spirit permeates his compositions.”

Classical music may have been sufficiently marginalised in the public realm to make it impossible to imagine a classical artist breaking through to mainstream audiences in the manner that Liszt did, but nevertheless, Gerstein is in no doubt that his mastery, talent and charisma would still make for an exceptional combination today. “I think his enduring popularity, and the widespread admiration of his works leaves no doubt that he continues to be a ‘superstar’,” he notes. For his part, Dr Hilmes is even more emphatic. “Today’s superstars would look like little school-boys compared to Franz Liszt.”

By Clemency Burton-Hill

You must be logged in to post a comment Login