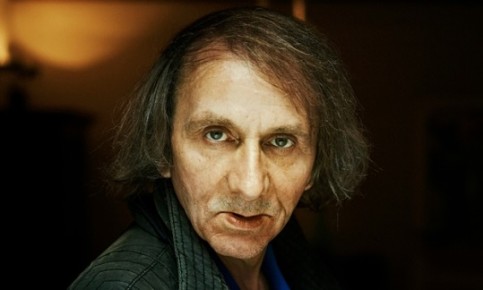

Shadowed by the plain-clothes police protection officer that now follows him round the clock, Michel Houellebecq, France’s most successful living writer, shuffles into his Paris publisher’s office. His quiet, otherworldly aura is enhanced by the anti-fashion statement of this ageing literary enfant terrible: too-short cord trousers that swing round his ankles, a C&A parka he is rarely without, comfortable shoes and the black backpack he takes everywhere containing his stash of Philip Morris cigarettes, which he smokes between his middle and ring fingers, smoothing his frizzy combover with a nicotine-stained finger.

“It fosters seclusion,” he says of life under constant police guard since January’s terrorist attacks on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. “You concentrate and get on with what you have to do. It reduces your social life.”

It is set in France in 2022, where the Socialist president François Hollande’s second term has led to such turmoil that extreme-right “nativists” and Muslim youths stoke violence in the streets. The final round of the presidential election sees the far-right Marine Le Pen facing the talented and ambitious Muhammed Ben Abbes of France’s new party, the Muslim Fraternity, who sweeps to power backed by all the mainstream parties keen to keep Le Pen out. Under Ben Abbes, order is restored, Islamic law comes into force, polygamy is encouraged, women are veiled and the troublesome unemployment rate finally drops after women are removed from the workplace and sent back into the home. All is told through François, a middle-aged, spiritually barren academic, who between paying for sex and eyeing up his students, mulls over whether to convert to Islam to get ahead.

But on 7 January this year, the day the controversial novel was published, horror struck France. At 8.20am, Houellebecq was on breakfast radio giving his first long interview about the book, which even before publication had stoked charges that it was Islamophobic provocation. Asked about his 2002 acquittal over inciting racial hatred after saying Islam was “the stupidest religion”, he said he had changed his mind upon reading the Qur’an and that he now felt Islam could be negotiated with. A few hours later, two French brothers walked into the offices of the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, which had published caricatures of the prophet Mohammed, and shot dead 12 people, including some of France’s best-known cartoonists, later killing a Muslim policeman who confronted them in the street. Houellebecq had been on Charlie Hebdo’s front cover that morning, depicted as a haggard Nostradamus preparing to celebrate Ramadan. It was a coincidence that the attacks happened on the day Houellebecq’s book was published but it dragged him inescapably into events. The next day, the Socialist prime minister, Manuel Valls, seeking to unite the nation against what he deemed the hateful fingerpointing at ordinary Muslims, said: “France is not Michel Houellebecq … it is not intolerence, hatred and fear.” The novelist cut short his promotional tour and fled to the mountains. A day later, the gunmen’s accomplice, Amedy Coulibaly, shot dead four people at a Kosher supermarket in Paris.

We meet in May and plan to speak again in August, just before the book is published in Britain. But by then, after a summer in which he has fallen out with Le Monde, he doesn’t want to talk about it any more. In Paris in the late spring, Houellebecq lights a cigarette and takes a drag. “I was at home. It was my publisher who called to tell me – she was scared,” he says of the attacks. After living in Ireland for 10 years, mainly in order to pay less tax, he returned to France in 2012, having decided he “wanted to speak French”, and now lives in a flat in a non-descript towerblock in a quiet, working-class Chinese district of Paris’s 13th arrondissement. It’s a modest place, a picture of his famous Welsh corgi, Clément, now deceased, sharing a bookshelf with his childhood stuffed toys. He says that when news of the Charlie Hebdo attack came, he at first wasn’t worried about his friend, the economist Bernard Maris, who wrote a column for the weekly.

“He wasn’t a cartoonist and I don’t think he’d ever written the word Islam in any of his opinion columns about economics … But everyone who was there at the editorial meeting was targeted …” When Maris’s death in the attacks was announced, Houellebecq said: “It was the first time in my life that someone I loved was murdered.” He broke down in tears in a TV interview before stopping all media promotion of his book. “I was just depressed,” he says now.

In the wake of the attacks, a number of high-profile people considered to be at risk from jihadist terrorists got police protection. Houellebecq said he didn’t ask for it; his publisher consulted police, who thought it would be a good idea.

Submission appeared at the height of a long build-up of tension in France in which books, media and magazines had for months been relentlessly focusing on Islam as if the religion itself was a threat to France. The essayist Eric Zemmour had topped the non-fiction bestseller list with Le Suicide Français, in which he argued that millions of Muslims might be colonising and transforming the country and should be “repatriated”. Houellebecq, who says he hasn’t read Zemmour, was accused of stoking this further by coming up with a highly implausible scenario in which an Islamist party takes over France, when Muslims in reality make up only a small percentage of the population.

Some intellectuals said Houellebecq had been “irresponsible”. The media pressed him to apologise. Where once he was a bolshy rebel outsider, he now has a godlike status as France’s biggest literary export and, some say, greatest living writer – so what he says counts. But he denies any “responsibility”.

“It’s not my role to be responsible. I don’t feel responsible,” he says. “The role of a novel is to entertain readers, and fear is one of the most entertaining things there is.”

To him, the fear in Submission comes in the dark violence at the novel’s start, before the moderate Islamist party comes to power. Was he deliberately playing on a mood of fear in France? “Yes, I plead guilty,” he says. For Houellebecq, the job of a novelist is foremost to hold a mirror up to contemporary society.

He says the stream of books and magazine covers playing on fear of Islam “has effectively become obsessional”. Is his book part of that? “Certainly, certainly,” he says.

“But I don’t particularly feel like apologising. It’s impossible to increase the proportion already given to Islam in the news. We’re already nearly at 100%.”

Houellebecq insists that Submission is absolutely not an Islamophobic novel. “Everything returns to order … the moderate faction manages to control its extremists, which is far from a given at the moment.” But after the Charlie Hebdo attack, in terms of freedom of expression, he has argued that anyone should have the right to write an Islamophobic novel if they choose.

I ask him if, as he has been accused, he hates Islam. “I think about it very little,” he says. “Well, I suppose I thought about it a little more this time …” he adds, trailing off.

After he was acquitted in court for saying Islam was “the stupidest religion”, has he changed his mind?

“I don’t know if I’ve really changed my mind,” he says. “It’s true that reading the Qur’an is rather reassuring. So I said [when Submission came out in France] that I was reassured after having read the Qur’an. That said, maybe I hadn’t thought it through enough before saying that, because objectively, there’s just as little chance of Muslims reading the Qur’an as Christians reading the Bible. So what really counts in both cases is who is the clergy, or middleman, or interpreter. And in the case of Islam, that’s very open.”

He takes a drag on his cigarette. Talking to him sometimes feels like winkling a cockle out of a shell: the long silences, the folded arms to protect himself. Unlike almost every writer promoting a book, there is no prepared spiel.

Is he Islamophobic?

“Yes, probably. One can be afraid,” he replies. I ask him again: you’re probably Islamophobic? “Probably, yes, but the word phobia means fear rather than hatred,” he says. What is he afraid of? “That it all goes wrong in the west; you could say that it’s already going wrong.” Does he mean terrorism? He nods. Some might say that’s a tiny percentage of people, I begin … “Yes, but maybe very few people can have a strong effect. It’s often the most resolute minorities that make history.”

He has argued in interviews that Islamophobia, or fear of Islam, is definitely not a kind of racism and that the judges’ decision to acquit him in 2002 proved that.

Houellebecq flatly denies he is a provocateur. “No, no. A provocateur is someone who goes too far just to get on people’s nerves … A good provocateur knows who he’s going to shock. I’m absolutely incapable of predicting that … It’s always a surprise every time.”

He feels that, although he has speeded up events to 2022, the premise of an Islamist party coming to power in France and facing Marine Le Pen is entirely plausible. Le Pen herself called the book “a fiction that could become reality”. To those who accuse Houellebecq of handing Le Pen a “Christmas present” with the novel, he says:

“I don’t think I’ll bring her votes. And anyway, she doesn’t need it.”

Houellebecq’s main target in Submission is what he believes is France’s limp and cowardly intellectual and political class. In Paris, the most visible change when he returned from self-exile three years ago was the number of homeless “that had really exploded in the 10 years I’d been away”, but in the nation as a whole he noticed the media obession with Islam (“it really wasn’t talked about before I left”) and, most importantly, he says: “the people’s great contempt for its elite: politicians, bosses, journalists … it was really very big.”

I first met Houellebecq seven years ago on one of France’s live TV literary chatshows that run late into the night. Wrapped in his parka under the sweltering lights, he was promoting his book of letters with the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, in which they complained of being “public enemies”, unfairly hounded. That night Houellebecq said he liked to live on the edge, that he liked driving “very, very fast” and making dangerous movements with the steering wheel, although he had stopped doing it.

It was around that time that his mother, who abandoned him to his grandparents as a baby, had written a book furiously slating her son, something Houellebecq has always refused to comment on. He has long maintained that he will “always be an abandoned child” but he said media intrusion into his private life “brings me out in eczema”. Born on the French island of La Réunion, he was raised by his grandmother in northern France, and worked debugging computers for the French agriculture ministry before the success of his celebrated first novel, Whatever, about the empty life of a 30-year-old software engineer. This summer he got into a furious spat with Le Monde over a series of descriptive pieces about him that he hadn’t authorised.

“He poses as a victim, as a sad and suffering person whom literature has allowed to rise above his destiny, but in reality he has become a tyrant,” one writer, who “Houellebecq admires”, told Le Monde, adding that he had surrounded himself with “the court of a Chinese emperor”.

The issue of Houellebecq’s parents – his mother appeared thinly veiled as a selfish, sex-obsessed hippy in Atomised – returns in Submission, in which the central character’s parents have died. Houellebecq’s mother died five years ago. He says the parents in Submission are nothing like his own. But the issue of religious conversion – another central theme of the book – is linked to parental death and loss.

“I think atheism becomes harder to bear after the problem of the death of someone close,” he says.

Some French media have asked if the novel’s title really refers to the position of women, marked by sexual performance, paid sex, polygamy, withdrawal from the workplace. Houellebecq had originally thought feminists would take issue with it.

“In fact, they haven’t taken it that badly,” he says. “That’s why people are unpredictable.”

Why does he think the issue of women in the novel hasn’t sparked a bigger response?

“I don’t know. It’s possible that in truth there aren’t really that many feminists.” Is he a feminist? “No, no.” A misogynist, as has been levelled against him? “No, no, not that either,” he says. “But it’s possible that feminism has slightly disappeared from women too … It’s been a long time since I’ve seen anyone expressing a feminist opinion. I can’t remember the last time. In France, anyway.” He feels his books have always been well received by women in France. Does he hate women? “No, not at all.”

Houellebecq says he’s given up on political parties and only votes in referendums. He is anti-Europe and says of the UK’s EU referendum: “I’m really counting on the UK to vote no, which could have a domino effect of the collapse of Europe.”

As in all of Houellebecq’s novels, Submission has an atmsophere of anguished ambiguity.

“One very important condition of writing a novel is not to try to understand everything,” he says. “It’s best to observe the facts without necessarily having a theory.”

With the characters in Submission all giving their competing views, encased in what has been called Houellebecq’s famous overarching clinical neutrality, some critics have said it’s hard to know what he really thinks.

“It’s deliberate,” he concludes. “No doubt because actually I think nothing at all.”

Should we believe that he thinks nothing at all? Is he a twisted provocateur? That is the riddle that Houellebecq deliberately likes to leave unsolved.

Interview by Angelique Chrisafis

You must be logged in to post a comment Login