These days, many people, particularly cinephiles, or simply just people with a special and more than fleeting and/or passing interest in cinema, may wonder, “Where should I begin in regards to watching great movies? Which are the key works of this medium and why? Why is it important that I watch movies that are mostly not even popular anymore and even sometimes hard to find? Why should I watch this forgotten piece of celluloid? Where do my favorite movies come from?”

Well, we’ve humbly compiled a (partially subjective and arbitrary, of course, these things are always at least partially subjective and arbitrary, as there can be no absolutes in art) list of 30 films any person with a real, actual interest in cinema should watch at least once (although many times repeated viewings are practically required) in their lifetimes, and why.

Please note the films on this list are ranked in alphabetical order.

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick. (1968, USA).

What can possibly be said about “2001: A Space Odyssey”? It changed and renovated cinema, audiovisual communication, popular culture, science fiction and contemporary narrative forever, and predicted the iPad and many of the advances in technology we now take for granted, among many other things.

Kubrick painted a supremely beautiful and astonishing fresco of the History of the Universe and the History of the Human Species, where the groundbreaking narrative encompasses man’s preternatural hubris, destructive and self-destructive impulses, his continuous strive for advance and discovery but also tendency towards violence and preoccupations with death, and the indifference and unspeakable vastness of our universe along with its infinite mysteries.

It illuminated and inspired an incredible amount of fellow filmmakers, practically every single one that came after him, among them Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Sydney Pollack, Ridley Scott, Andrei Tarkovsky, Federico Fellini and Woody Allen. It paved the way for films like “Solaris”, the “Star Wars” saga(s), “Alien”, “Blade Runner” and “Close Encounters Of The Third Kind”.

Never before had so-called “mainstream” cinema gone nearly this far, and never before had a film been so brazenly bold. cinema is what it is today because of “2001: A Space Odyssey”, and we have Stanley Kubrick and his infinite genius to thank for this.

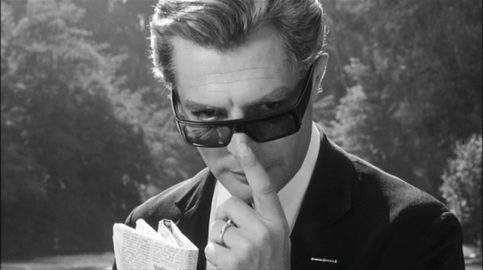

2. 8 ½, by Federico Fellini. (Otto E Mezzo, 1963, Italy, France).

Fellini’s masterpiece. After the enormous and international success of “La Dolce Vita” three years previous, the Italian genius set out to make a film about what it is to make films.

What resulted is a bittersweet ode to cinema, but also an examination of the creative mind and process and how the creative man deals with them.

Over the course of the film, we get to follow our protagonist, the successful and desired filmmaker Guido Anselmi (played to perfection by Marcello Mastroianni, of course), as he tries to manage his own complicated life, come to terms with his mistakes, losses and own selfishness, and face the responsibilities that come with being a successful artistic genius.

All of this is wrapped in a deep, serious, but also funny look at the life of dreams and the dreams of life.

3. Andrei Rublev, by Andrei Tarkovsky. (Andrey Rublyov, 1966, Soviet Union).

Behold a key piece in the world of cinematic art, and Tarkovsky’s definitive masterpiece. An impressive epic based on the life of the 15th century Russian icon painter of the title.

Tarkovsky’s intention was to portray the importance and prominence of the artists in the world that surround him, and the influence of the Christian religion in shaping Russian history.

During the time the film takes place, Russia was torn by the Tatar invasions and constant struggles to the throne.

“Andrei Rublev” is divided into a prologue, eight chapters and an epilogue. The prologue is only metaphorically linked to the rest of the film, while the epilogue is a montage of some of the titular character’s actual filmed masterpieces.

An essential as it is complex and rich masterpiece.

4. L’Avventura, by Michelangelo Antonioni. (1960, Italy).

Following and severely expending in what other filmmakers like Ford, Rossellini and Dreyer had hinted at before, Antonioni’s sixth film completely subverted, revolutionized and altered what had become narrative in cinema.

Eschewing completely the usual and conventional ways to make narrative cinema, Antonioni instead chose to make a film driven solely by its characters and their (very) hidden internal, emotional turmoils and the very gradual changes that come upon them, and the way they look at and regard life, themselves and love.

Portraying perfectly the lives of a privileged group of elite Roman people immersed in selfishness, ennui, boredom, non-communication, and above all meaninglessness, Antonioni chills his audience showing the immense fragility of life, existence, love, and any hint of meaning.

The sudden and obviously mysterious disappearance of a wealthy heiress is just an excuse for Antonioni to astonish us with his indelible and gorgeous art that will make you question many things that you take for granted.

5. Battleship Potemkin, by Sergei Eisenstein. (Bronenosets Patyomkin, 1925, Soviet Union).

Based on a true story about a group of crewmen and sailors who worked in a Russian battleship named, obviously, Potemkin, who rioted and rebelled against their superiors in 1905.

The film is divided into five acts: Men And Maggots, Drama On The Deck, A Dead Man Calls For Justice, The Odessa Steps and finally One Against All.

“Battleship Potemkin” is mostly famous and celebrated for its innovations in editing, employing an incredibly and extremely rapid and dynamic (for the time) style, which Eisenstein hoped would help make the audience sympathize with the sailors, and also, for the The Odessa Steps act, which depicts a fictional massacre of civilians enacted by the Czarist Empire of that time.

6. The Birth Of A Nation, by D. W. Griffith. (1915, USA).

This is the film that turned cinema from an occasional diversion for some people into what it is today.

To call it groundbreaking is an understatement. It showed that cinema could be a an exciting new medium for narrative, entertainment and art. All of them. All at the same time.

Griffith introduced narrative and technical innovations that helped shaped the medium like no other film.

7. Breathless, by Jean-Luc Godard. (À Bout De Souffle, 1960, France).

The official third entry of the French New Wave, after Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” and Resnais’ “Hiroshima, Mon Amour”.

Based on a screenplay first written by Truffaut based on a real story from 1952 to be directed by him, it was ultimately discarded by the director.

Godard read the screenplay, loved it, and asked his then best friend Truffaut if he would let him use it. Truffaut did, absolutely free of charge.

One of the first truly modern films, “Breathless” was a total success, influencing hundreds of films since then, with its focus on youth, beauty, so-called “coolness”, rebellion, total irreverence, dynamism, humor, fast-pacing, endless references to previous films, and, most importantly, pop culture; the disregard of conventions and rules, and the charisma of its protagonists, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg.

It is notable is its use of the famous jump-cuts, an original idea of the master and genius filmmaker revered by Godard, Jean-Pierre Melville.

8. Un Chien Andalou, by Luis Buñuel. (1929, France).

One of the first Surrealist films ever and without a doubt the most notorious and popular Surrealist film of its era, and the most influential one of all time.

Based on a screenplay by the director himself and Salvador Dalí, the film is more a collection of images and shots than an actual plot and has been called the first music video ever, as it uses, decades and decades before that medium came to existence, all the conventions and stylistic devices it has always utilized,

It also introduced violence to cinema like no other film before. Its most famous fragment, by far, is when the character played by Buñuel takes a razor, holds a young woman’s (played by Simone Mareuil who decades later would commit suicide by self-immolation) head steady, opens her left eye wide open and, after the film cuts to an extreme close-up of the eyeball, slits it completely with the razor (in reality, an eyeball of a dead calf was used).

9. Citizen Kane, by Orson Welles. (1941, USA).

The summit, the Everest of the cinematographic medium. There’s literally nothing that can be said about “Citizen Kane” that hasn’t been already said, either in words or by images.

To even invoke “Citizen Kane” and discuss its importance requires already previous and well-founded knowledge from the audience.

We’re in the presence of a work so essential, so innovative, so gigantic, that perhaps the best and most adequate thing that can be said is: “If possible, drop everything right now and run to see it, if you haven’t. If you have, run to see it one more time.”

Co-written by Herman J. Mankiewicz and produced, starred, co-written and directed by Welles, it was Welles’ first ever foray into anything remotely cinematographic, when he was only 25. How was he able to make “Citizen Kane” at all in that case? By watching Ford’s “Stagecoach” dozens of times, and asking technicians and/or people from the studio how one thing or another was made.

10. Days Of Heaven, by Terrence Malick. (1978, USA).

Five years after his unforgettable debut feature film “Badlands” took the world by surprise, Malick astonished the world with this film, his second feature, set in Texas just before the Great War but shot in Canada. Two orphans living in poverty, Linda and Bill, along with Bill’s girlfriend, Abby, flee Chicago where Bill accidentally killed his former employer, and set out to find work and a place to live as far away as possible, settling on a Texas plantation.

But that’s just the beginning, and, in any case, Malick uses this narrative and its twists you could say almost as an excuse to literally make visual poetry, expanding on what filmmakers like Ford, Antonioni, Visconti and Tarkovsky had already done and taking his cues from Kubrick and “2001: A Space Odyssey”. That is, the images, the sound, and the score by Ennio Morricone tell the story.

The images being amongst the most mesmerizing, arresting, gorgeous, unbelievable, breathtaking and jaw-dropping in the history of cinema, captured by Malick’s DP, Néstor Almendros, who had worked with people like Truffaut before and was actually going blind while the film was being shot. It is an out of this world, moving and poignant meditation on life and its fragility, love, greed and jealousy, set inside some of the most wondrous landscapes you’ll ever see.

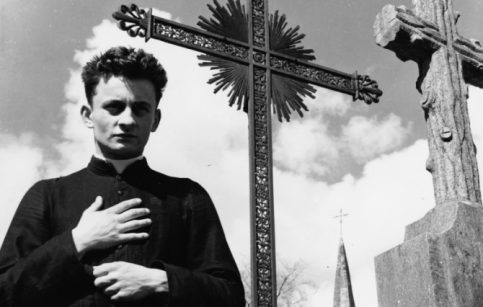

11. Diary Of A Country Priest, by Robert Bresson. (Journal D’Un Cure De Campagne, 1951, France).

This is the film that inspired Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver”, and the first masterpiece by the gigantic Bresson. The film where he started his revolution of the cinematographic medium.

At the time, the film was praised in part for the performance by its protagonist, Claude Laydu (who passed away in 2011), the country priest of the title, of course.

However, what Bresson always searched, looked for, yearned for, were, for lack of a much better word, anti-performances.

Laydu wasn’t an actor before the film and in the whole cast, there was only one professional actress.

Years later Bresson would put all his cinematographic thesis in his essential and seminal book “Notes On The Cinematographer”.

What we have here is an unforgettable and scarring look at pain, isolation, loneliness, despair, misery and doubt, and an extremely profound and poignant examination of what human beings must do to conquer pain and achieve redemption and grace.

12. Fireworks, by Kenneth Anger. (1947, USA).

The earliest surviving film by His Excellency Anger, it was made when the author was 20 years old at his parents’ house while they were away during a weekend.

One of the forefathers of experimental cinema, this 14-minute surrealist work explores sexuality, (homosexual) desire, fetishism and violence in a way that was utterly and absolutely revolutionary for its time.

Anger, a former child actor, was arrested after the film was released and the film itself was banned on the grounds of obscenity charges.

The California Supreme Court categorized the film as art, nevertheless.

In the words of Anger: “A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking a ‘light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to bed less empty than before. […] This flick is all I have to say about being seventeen, the United States Navy, American Christmas, and the Fourth of July.”

13. The Godfather, Part II; by Francis Ford Coppola. (1974, USA).

The first ever “respectable” sequel. The film that popularized sequels themselves. The first film to use the phrase “Part II” in its title.

Released the same year as another of Coppola’s essential masterpieces, “The Conversation”, “The Godfather, Part II” greatly expands on the story of the Corleones.

A film comparable to “Citizen Kane”, it shows in great detail Michael Corleone’s “moral” downfall as a human being and the absolute hypocrisy of his very existence, simultaneously with his triumph over all his enemies and obstacles, and his father’s rise as both a family man and the leader of the Sicilian Mafia in New York.

Simply put, it’s the greatest and most essential gangster movie ever made, even though to say that is terribly reductionist, as this film is so much more. Those who’ve seen it endless times will know what that means.

14. Goodfellas, by Martin Scorsese. (1990, USA).

The prime example of postmodernism in film. Scorsese takes the audience on a 146-minute ride that makes them feel like they’re going to crash any second.

Using a dynamic, fast-as-hell and intelligent style, Scorsese immerses the viewer in the lives and deeds of the film’s characters, never allowing the viewer to take a breath, and almost forcing them to understand why the characters do what they do and why the events that occur do and why they occur the way they do.

It’s impossible to imagine 90s cinema (especially the films from that era that are now considered “classics”) and what followed it without “Goodfellas”.

So, what was Scorsese’s aim with this magnificent film?

“To begin [the film] like a gunshot and have it get faster from there, almost like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer. I think it’s the only way you can really sense the exhilaration of the lifestyle, and to get a sense of why a lot of people are attracted to it”.

15. Journey To Italy, by Roberto Rossellini. (Viaggio In Italia, 1954, Italy).

Partially based on the novel “Duo” by Colette, and starring Ingrid Bergman (Rossellini’s true-life wife at the time) as Katherine and George Sanders as Alex.

Leaving behind his earlier Neorealist work, but still holding on to some of its features, Rossellini shot this modest film, perhaps his masterpiece.

The film follows Katherine and Alex Joyce, a married couple from the United Kingdom, as they travel to Italy to get rid of a property a recently deceased uncle of Alex left him in his will.

The couple’s relationship is in its last stages, and where was perhaps love at one time, there is now only contempt and resentment.

The premise is just an excuse for Rossellini to explore two empty, selfish personalities who struggle not only to accept each other but themselves, and cannot decide if they still love each other or if they ever did in the first place.

A gorgeous and unique film that precedes what other filmmakers like Antonioni would later do in their most celebrated works.

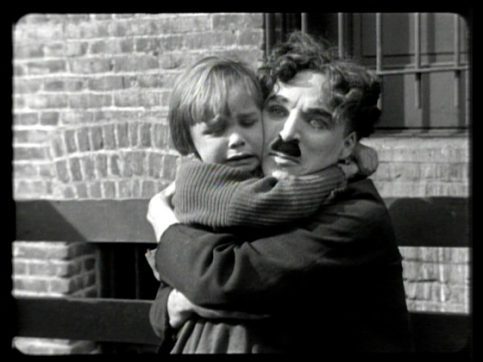

16. The Kid, by Charlie Chaplin. (1921, USA).

The greatest success for Chaplin up until that point, “The Kid” is a supremely powerful ode to love between a father and a son.

A single mother is discharged from a charity hospital with a newborn boy. She decides to abandon the child and writes a note begging whoever finds him to love and care for him.

Our beloved Little Tramp is the one who reluctantly ends up with the responsibility in his hands.

Five years later, they’re a loving, lovable pair of partners in petty crime, until a series of unexpected, suspenseful, action-filled, sad and hopeful events changes everybody’s lives forever.

As the introduction itself declares: “A picture with a smile, and perhaps, a tear”…

17. Nosferatu, by F. W. Murnau. (Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie Des Grauens, 1922, Weimar Republic).

One of the first vampire films and the first “Dracula” cinematographic adaptation ever.

Perhaps the greatest horror film ever, it showcases Expressionism in all its gorgeous glory through cinema.

Lacking the rights to the Bram Stoker novel, Murnau changed the title (Nosferatu meaning “undead”) and the characters’ names (Count Dracula became then Count Orlock and Jonathan Harker Thomas Hutter, for example).

Nevertheless, Stoker’s estate sued and won. All copies of the film were to be destroyed; however, fortunately one copy survived and was then copied and bootlegged all over the world.

18. Olympia, by Leni Riefenstahl. (1938, Germany).

One of the most influential and ground-breaking films ever made.

Dancer, actress, photographer, screenwriter, producer and director Leni Riefenstahl became National-Socialist Germany’s official filmmaker and documenter, by mandate of Adolf Hitler himself. She’s been called “the most powerful woman in Nazi Germany”.

It was 1936 and Berlin was going to be the host of the International Summer Olympics. Adolf Hitler wanted what he saw as the glory of National-Socialist Germany to be portrayed forever in an astonishing and unforgettable fashion in order for it to be shown to the whole world.

The one responsible for this task would of course be Riefenstahl herself.

Riefenstahl innovated with the use of dollies, extreme-close-ups, Dutch angles, and never-before seen montage styles.

“Olympia” is the ultimate celebration of and ode to the human physique and prowess, as well as the human species’, talent, struggles, athleticism and duress.

Released originally in two different parts due to its length, “Olympia” is rightfully still celebrated and admired for what it is.

19. Paisan, by Roberto Rossellini. (Paisà, 1946, Italy).

A Neorealist masterpiece by Rossellini, where the world would see his style come to full fruition. The second in his trilogy about World War II and its aftermath, after “Rome Open City” and followed by “Germany, Year Zero”.

Just like both films that preceded and followed it, “Paisan” was shot in a guerrilla documentary style with non-actors playing the characters in real locations, something never seen before in a fictional narrative film.

Divided into six chapters, it better portrays, than almost any other film, how nobody really wins in war and the consequences that Italy, especially its poor, suffered after losing to the Allies.

A real, unmissable treasure.

20. The Passion Of Joan Of Arc, by Carl Theodor Dreyer. (La Passion De Jeanne D’Arc, 1928, France).

The supreme masterpiece of the supreme Carl Theodor Dreyer.

The Danish filmmaker was invited to make a film in France. He decided on Joan Of Arc and her trial and subsequent execution at the stake by the English as his subject.

He hired stage actress Renée Jeanne Falconetti to play Joan in her only work for cinema.

In the making of the film, Dreyer employed a myriad of unique techniques to bring his vision to life.

He had holes dug in the ground to make extreme low angle shots, and he had an entire concrete soundstage of medieval style built to resemble the prison at Rouen where Joan Of Arc spent the last months of her life. He forbade all actors to use any makeup. In the case of Falconetti, this was done so her facial expressions of suffering, pain, martyrdom, despair and doubt in extreme close-up would be astonishingly translated to celluloid.

The result is one of the most important works of art of the 20th Century and there for all to silently witness.

21. Persona, by Ingmar Bergman. (1966, Sweden).

Persona (Latin): person, individual, persona, character, role, part, mask, personality.

What is a person? What shapes a person? What differentiates one person from another? Why do we wear masks and pretend they are indeed ourselves? Why do we choose the masks we choose? What do we hide behind our masks, behind our faces? How do we react to the world that surrounds us? Why do we react in that way? What mask do we choose to represent those reactions? Why do we choose it?

Like never before in the history of cinema, Ingmar Bergman asks this question and many more directly to the audience, and challenges it to answer, or to even have an answer.

Like Camille Paglia said about the film:

“When I saw Bergman’s “Persona” at its first release in New York in 1967, I felt that it was the electrifying summation of everything I had ever pondered about Western gender and identity. The title of my doctoral dissertation and first book, “Sexual Personae,” was an explicit homage to Bergman. On a British lecture tour for the National Film Theatre in 1999, I asked to sleep with “Persona” — whose five reels, like holy icons, rested in two silver cans next to my bed.”

The young, naïve, inexperienced, overly-trusting, solitary nurse Alma (“Soul” in Latin and Latin-derived languages), played by Bibi Andersson, is tasked to care for the near-catatonic but “healthy” actress Elisabet, played by Liv Ullmann in one of the greatest performances in history.

(It is a marvel to behold Ullmann saying infinitely more with a look and a subtle expression of her face without opening her mouth at all, than with pages and pages of [expository] dialogues or monologues, screams, shrieks, tears or dozens and dozens of close ups of her gorgeous face).

What follows will never, ever leave the viewer’s mind.

Since its very premiere, “Persona” has lent itself to truly massive and endless amounts of analysis, interpretations, references, homages and criticisms. All of them range from pure cinematic to philosophical, cultural, counter-cultural, sexual, popular culture, political, psychological, psychiatric, psychoanalytic/Freudian, sociological, biological and even economic ones.

One thing is absolutely certain: It has become impossible to imagine and understand cinema and contemporary culture without “Persona”.

22. Psycho, by Alfred Hitchcock. (1960, USA).

It is perhaps the first American modern film. It certainly helped begin the end of the classicism in American cinema.

Just like Michael Powell’s “Peeping Tom” from the United Kingdom just a couple of months previous, “Psycho” was enormously groundbreaking in its depiction of violence, sexuality and the points where they meet and intersect in “mainstream” entertainment.

Marion Crane steals money in cash from one of her boss’ associates, and as she’s running away, ends up in the Bates Motel, where there are 12 rooms and 12 vacancies. She is tended to by Norman Bates, the son of the owner, Mrs. Bates. She takes a shower and then… we all know what happens and that is what changed cinema forever. Among other things, Bernard Hermann’s string composition during the scene might as well be the first time atonal music was used in an important, “mainstream” film.

It’s now considered the first slasher film, though that “title” should perhaps fit the aforementioned “Peeping Tom” better, being, that, you know, it was actually released before.

Nevertheless, it is “Psycho” that forever changed and reshaped cinema, especially horror cinema.

23. Rashomon, by Akira Kurosawa. (1950, Japan).

Literally the film that put Japanese cinema on the map and brought it to Western audiences, “Rashomon” is one of Kurosawa’s most cherished masterpieces.

Making use of narrative and subverting it like it was never before seen in history, “Rashomon” concerns the repercussions of a terrible, unfathomable crime.

Such a crime is recounted through the accounts/stories of four different characters and all of such accounts differ in key points. Who’s telling the truth out of the four, if anyone? Why would any of them lie?

An enigma as mysterious as the human condition itself.

24. Sátántangó, by Béla Tarr. (1994, Hungary).

Based on the László Krasznahorkai novel of the same name and adapted by both the director and the novelist, “Sátántangó” tells, over the course of seven hours, the story of a desolate and remote rural community somewhere in Hungary that’s immersed in misery, and where most of the inhabitants favor alcohol over almost anything else almost the entire time.

The entire community is shaken when rumors arise that the legendary Irimiás, previously presumed dead, is coming back to the town with great business.

Irimiás indeed returns, but his arrival coincides with a most horrendous, tragic and gruesome event, and the result of his return ends up being something nobody could have expected.

The film is told in a non-chronological order, divided into 12 chapters, and several scenes and events are revised and shown more than once from different points of view, playing with and changing the viewer’s perspectives and judgments on the occurrences and characters. Gus Van Sant reveres the film to such a degree that he openly took the narrative structure of it and applied it to his own great “Elephant” (a movie that also borrowed several elements from Alan Clarke’s own “Elephant” as well).

“Sátántangó” is the pinnacle of what many call now “slow cinema”, being, well, quite deliberately paced and being assembled only from very long cuts. In “Sátántangó”, each take lasts an average of 150 seconds; two and a half minutes.

25. Seven Samurai, by Akira Kurosawa. (Shichinin No Samurai, 1954, Japan).

One of the first action movies as we know them today, this is also an epic adventure drama about honor, loyalty, bravery, trust and teamwork.

A group of poor villagers hire the seven samurai of the title to help and protect them against a band of thieves who bully and terrorize them and steal their crops.

Astonishing from the first frame to the last one, this 3-and-a-half hour epic film will leave the viewer speechless when it all ends.

A most vital and powerful work of art as any that will be found among the rest of the 20th century.

26. Stagecoach, by John Ford. (1939, USA).

Based on a short story by Ernest Haycox and adapted by Dudley Nichols to be filmed by Ford.

The film that taught Orson Welles how to be a filmmaker after, according to the own filmmaker, having seen it over 40 times.

Another gigantic filmmaker that was greatly influenced by Ford and particularly “Stagecoach”, is Akira Kurosawa, who borrowed heavily from Ford’s style when making some of his films, particularly his samurai films, including “Seven Samurai” itself.

The quintessential Western that introduced audiences around the world to several of the staples, conventions and tropes of what is known today as the great Western genre.

To put it quite simply, practically all the Westerns you’ve seen wouldn’t be what they are if it weren’t for this film.

Impossible to disregard, as blunt as that may be.

27. Sunrise: A Song Of Two Humans, by F. W. Murnau. (1927, USA).

Based on the short story “The Excursion To Tilsit” by Hermann Sudermann and adapted by Carl Mayer.

Though silent, it’s one of the first films to include a synchronized soundtrack of musical score and sound effects, made possible by the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system.

It’s a tale filled with twists about love, betrayal, temptation, redemption and forgiveness.

The film was unusual at the time due to it being directed by Murnau, a German filmmaker, in his usual German Expressionistic style, having relatively few intertitles, featuring tracking shots and having characters that are never named.

28. Tokyo Story, by Yasujiro Ozu. (Tokyo Monogatari, 1953, Japan)

An aging couple with five children, one of them deceased, decide to travel to Tokyo to visit three of his surviving children. Their youngest daughter, Kyoko, lives with them and stays in order not to miss school.

This is the film that cemented both Ozu as a master and leading filmmaker along with his style.

Shot as it would later become usual to Ozu by a camera that doesn’t move and stays fixed at a very low angle, that also allows us to see all the action unfold without missing a single movement, expression or event that is absolutely essential to the particular universe of the film.

It also features an episodic narrative, where events and parts of the story are abbreviated and never actually shown.

A classic tale on aging and the importance to come to terms with one’s mistakes as well as others’ and with mortality itself.

29. A Trip To The Moon, by Georges Méliès. (Le Voyage Dans La Lune, 1902, France).

The first ever science fiction film; the film that would officially and internationally bring and introduce the genre into the cinematographic art.

To write and make this film Méliès took Inspiration from the writings of Jules Verne among many other sources, like H. G. Wells’ “The First Men In The Moon”, and the Jack Offenbach operetta “Le Voyage Dans La Lune”.

The film depicts a journey to the moon where the astronomers are attacked by some of the moon inhabitants; they fight them off and return to Earth.

With this film, Méliès literally made magic with the use of filmed celluloid, camera cuts and montage.

Among the hundreds of references and homages that could be mentioned are the Smashing Pumpkins’ video for their song “Tonight, Tonight” directed by Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris and, of course, Scorsese’s loving ode “Hugo”.

30. Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory In Lyon, by Louis Lumière. (La Sortie De L’Usine Lumière À Lyon, 1895, France).

This film is exactly what the title describes.

A one-minute documentary film depicting a natural scene in late 19th century France by one of the two first filmmakers in history, who also happened to create cinema to begin with.

Considered by many to be the first ever film, though this has been debated as some people consider the two-second “Roundhay Garden Scene”, by Louis Le Prince (1888, United Kingdom, France) made seven years, earlier to hold that title.

Author: Lee Schroeder

Source:

You must be logged in to post a comment Login