My wife, Susan, and I lost our minds. For more than two weeks at the beginning of February, we were locked in a ritual that became the center of our day, the center of our conversation—watching first the six-hour original 1979 BBC version of John le Carré’s “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” (not to be confused with the competent but muffled new movie version), and then its six-hour sequel from 1982, “Smiley’s People.” We would watch one episode each evening after dinner. Late at night, I would often creep back into the study and watch the episode again, just to be sure I had understood all of it, savored all of its intricacies, noted its omissions and implications. I needed to review what I knew and didn’t know at every stage—not just what we had seen, but what had happened off-camera, what had happened in the interim between the episodes, and also what might have been. After thinking everything over, I would discuss it with Susan—when she would let me. In obsessional situations like this, your overflowing pleasure can destroy someone else’s happiness. You want to blurt out everything.

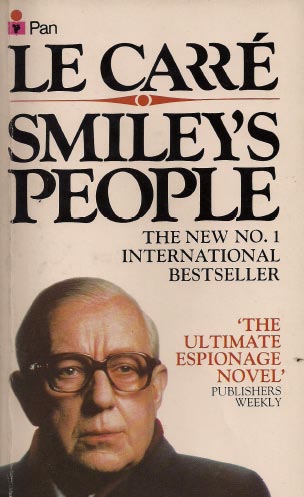

I know there are millions of people who adore mystery novels as a pleasurable brain-tease, reading one book after another with full absorption and then quickly forgetting it. I love Raymond Chandler, a great American writer who, in effect, created Los Angeles imaginatively almost as fully as Faulkner created Mississippi or Melville the sea, and I admire the contemporary fiction of Peter Blauner, who writes humanist thrillers, a seeming contradiction in terms that he pulls off. But I’ve never been addicted to mysteries or to anyone’s spy novels but John le Carré’s. Why this time? I suppose the reasons for fascination lie in the suggestive complication, the interlocking puzzles built into le Carré’s material and in George Smiley’s character, as interpreted by Alec Guinness. His performance is one of the great literary-cinematic creations of the post-war era, an actor’s masterpiece.

Most of you know the situation in “Tinker Tailor.” There’s a Soviet mole within the high command of Britain’s M.I.6.—“the Circus” in le Carré’s slangy nomenclature. The mole has been there for years, and Control (Alexander Knox), the aging, desperately ill director of the Circus, tries to root him out. When a possibly fruitful operation is blown, Control is destroyed—forcibly retired (he then dies), taking Smiley, his deputy, down with him. But new evidence turns up, and Smiley is called out of retirement and given the resources to find out who the traitor is. He interviews many agents, draws on old memories, reads old files, sifting and sorting as he tries to put together fragments and find a pattern in a series of blown operations that would suggest a single treacherous hand, a single line of intent. Most of his work in “Tinker Tailor” is intellectual; the active spying, with rescues, entrapment, intimidation, and the like, comes in “Smiley’s People.” Physically, the action is low-tech, paper-bound, and staged, generally, in rather small rooms. Britain was still shabby then, and under-equipped—a country crestfallen and ironically resentful over its diminished role in world affairs. Most of the time, we could be inhabiting the furniture of Smiley’s mind.

So here’s the reason for fascination: in Arthur Hopcraft’s adaptation of le Carré’s 1974 novel, nothing is explained to you. No one conveniently recapitulates what is known and not known. At every given stage, you know as much as Smiley—no less and no more—and you are there, along with him, trying to make sense of assorted bits of testimony, experience, documentary evidence. You feel almost as if you were a member of a secret organization, and you accept what inevitably accompanies a culture of secrecy—that everyone is lying, or at least concealing something or playing some game. As Smiley makes his way through the fog, “Tinker Tailor” becomes the ultimate procedural, and yet it’s a powerfully emotional experience from the start. Repeated betrayal is right at the heart of it, and no one has been traduced more grievously than Smiley, whose wife, Ann (Sian Phillips), has had affairs with many men and has been drawn, unwittingly, into Moscow’s plan to protect the mole. For Smiley, the situation is infinitely dangerous. Though he never speaks this way, his own honor, as well as England’s, has been damaged.

Alec Guinness was just under six feet, a moderately large man with an accumulating gut in 1979 (he was in his middle sixties when “Tinker Tailor” was shot). Guinness had been one of the great stalwarts of British film acting in the forties, fifties, and sixties—David Lean’s favorite man, a genial yet commanding presence in such easy, whimsical comedies as “Kind Hearts and Coronets,” “The Man in the White Suit,” and “The Lavender Hill Mob.” He was not the actor you would most likely think of to play a hero, though George Lucas, knowing that he had enormous gravity to draw on, had cast him as the light saber-wielding, wisdom-dispensing Obi-Wan Kenobi in “Star Wars.”

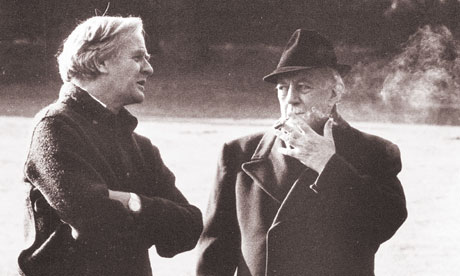

Smiley is the real-world payoff on Lucas’s insight: a genius in a bowler hat and thick glasses, not a robed swami speaking in gnomic riddles. Guinness’s Smiley is circumspect yet fearless. As Guinness plays him, shading his rounded, musical baritone into infinite tonal varieties, Smiley is bland and quizzical, except when he has to be direct and masterful; silent, except when he absolutely needs to speak; vague about what he believes, except when he’s roused by some expression of cynicism to defend patriotism and loyalty. Even though we get to know his Smiley well, Guinness can always startle us—there seems to be no end to his subtlety, his complexity, his shafts of anger, his refusal, on so many occasions, to get angry. When Rickey Tarr (Hywell Bennett), the Circus’s rogue agent, attacks him physically, he isn’t even put out. He simply goes on talking where he left off. After all, he provoked Ricky. From his point of view, there’s nothing strange about the attack, which, in any case, confirmed what he wanted to know. What a man! He seems the ultimate in equanimity, purpose, and effectiveness. As directed by John Irvin (“Tinker Tailor”) and Simon Langton (“Smiley’s People”), the performance has an almost Shakespearian richness, though with layers of stone and frost lining the outer edge of the strong emotions churning inside.

One can understand how Ann might have found him an infuriating husband. Smiley never answers a question that he doesn’t care to answer. When people tease him with enraging regularity about his straying wife, Guinness only grimaces. Smiley has been so frequently and publicly cuckolded that people underestimate him; they don’t realize that, by the end of “Tinker Tailor,” he is, after the Prime Minister, possibly the most powerful man in England. He’s so mild and polite—never getting excited, never rushing—that it takes even us, his intimates, quite a while to realize how driving and single-minded he is. That quality becomes much more obvious in “Smiley’s People,” when he works implacably, with a kind of measured relentlessness, to destroy Karla (Patrick Stewart), the genius of Moscow Center, the head of Soviet foreign intelligence, and Smiley’s nemesis for over thirty years. By the end of “Smiley’s People,” he has becomes a kind of secular god of intelligence (in all senses of the words), an arbiter of what is relevant and what isn’t, what is worth knowing and what is trivial. Isn’t that what we all want—judgment? A way of knowing what is important amid a welter of impressions and emotions?

As Smiley gets closer to his goal in “Smiley’s People,” he becomes not jubilant but more withdrawn than ever, even depressed. “Smiley’s People” was shot in 1982, but the concluding scenes—set in a rain-soaked Berlin, of course—presage the end of the Cold War, the struggle which has given Smiley’s life whatever meaning it has. There is little left for him to do, and, anyway, he’s temperamentally incapable of triumph. But we are ready to start all over again, as I certainly did when, hesitating no more than a few days, I put “Tinker Tailor” back into the DVD player. There may be more to pull out of this, I told myself. It’s hard to think of any other sustained fiction in which knowledge, so centrally, is the highest form of pleasure.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login