One morning in may, the existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom was recuperating in a sunny room on the first floor of a Palo Alto convalescent hospital. He was dressed in white pants and a green sweater, not a hospital gown, and was quick to point out that he is not normally confined to a medical facility. “I don’t want [this article] to scare my patients,” he said, laughing. Until a knee surgery the previous month, he had been seeing two or three patients a day, some at his office in San Francisco and others in Palo Alto, where he lives. Following the procedure, however, he felt dizzy and had difficulty concentrating. “They think it’s a brain issue, but they don’t know exactly what it is,” he told me in a soft, gravelly voice. He was nonetheless hopeful that he would soon head home; he would be turning 86 in June and was looking forward to the release of his memoir, Becoming Myself, in October.

“I haven’t been overwhelmed by fear,” he said of his unfolding health scare. Another of Yalom’s signature ideas, expressed in books such as Staring at the Sunand Creatures of a Day, is that we can lessen our fear of dying by living a regret-free life, meditating on our effect on subsequent generations, and confiding in loved ones about our death anxiety. When I asked whether his lifelong preoccupation with death eases the prospect that he might pass away soon, he replied, “I think it probably makes things easier.”

Many of Yalom’s fan letters are searing meditations on death. Some correspondents hope he will offer relief from deep-seated problems. Most of the time he suggests that they find a local therapist, but if one isn’t available and the issue seems solvable in a swift period—at this point in his career, he won’t work with patients for longer than a year—he may take someone on remotely. He is currently working with people in Turkey, South Africa, and Australia via the internet. Obvious cultural distinctions aside, he says his foreign patients are not that different from the patients he treats in person.

“If we live a life full of regret, full of things we haven’t done, if we’ve lived an unfulfilled life,” he says, “when death comes along, it’s a lot worse. I think it’s true for all of us.”

“For, as I draw closer and closer to the end, I travel in the circle, nearer and nearer to the beginning.”

“I’ll do the sixth revision next year,”

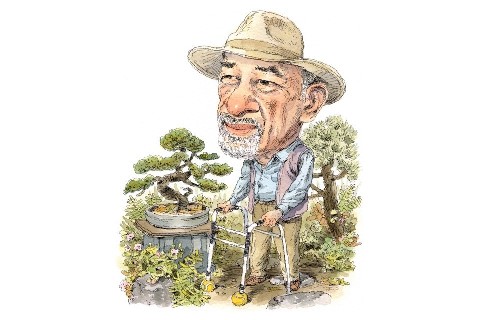

he told me, as nurses came in and out of the room. He was sitting in a chair by the window, fidgeting. Without his signature panama hat, his sideburns, which skate away from his ears, looked especially long.

Although he gave up teaching years ago, Yalom says that until he is no longer capable, he’ll continue seeing patients in the cottage in his backyard. It is a shrink’s version of a man cave, lined with books by Friedrich Nietzsche and the Stoic philosophers. The garden outside features Japanese bonsai trees; deer, rabbits, and foxes make occasional appearances nearby.

“When I feel restless, I step outside and putter over the bonsai, pruning, watering, and admiring their graceful shapes,” he writes in Becoming Myself.

“I wanted to rehumanize therapy, to show the therapist as a real person,” he told me.

Yalom is candid, both in his memoir and in person, about the difficulties of aging. When two of his close friends died recently, he realized that his cherished memory of their friendship is all that remains.

“It dawned on me that that reality doesn’t exist anymore,” he said sadly. “When I die, it will be gone.”

The thought of leaving Marilyn behind is agonizing. But he also dreads further physical deterioration. He now uses a walker with tennis balls on the bottoms of the legs, and he has recently lost weight. He coughed frequently during our meeting; when I emailed him a month later, he was feeling better, but said of his health scare,

“I consider those few weeks as among the very worst of my life.”

He can no longer play tennis or go scuba diving, and he fears he might have to stop bicycling.

“Getting old,” he writes in Becoming Myself, “is giving up one damn thing after another.”

“My wife matches me book for book,”

he told me at one point. But although Yalom’s email account has a folder titled “Ideas for Writing,” he said he may finally be out of book ideas. Meanwhile, Marilyn told me that she had recently helped a friend, a Stanford professor’s wife, write an obituary for her own husband.*

“This is the reality of where we are in life,” she said.

Early in Yalom’s existential-psychotherapy practice, he was struck by how much comfort people derived from exploring their existential fears.

“Dying,” he wrote in Staring at the Sun, “is lonely, the loneliest event of life.”

Yet empathy and connectedness can go a long way toward reducing our anxieties about mortality. When, in the 1970s, Yalom began working with patients diagnosed with untreatable cancer, he found they were sometimes heartened by the idea that, by dying with dignity, they could be an example to others.

Death terror can occur in anyone at any time, and can have life-changing effects, both negative and positive.

“Even for those with a deeply ingrained block against openness—those who have always avoided deep friendships—the idea of death may be an awakening experience, catalyzing an enormous shift in their desire for intimacy,”

Yalom has written. Those who haven’t yet lived the life they wanted to can still shift their priorities late in life.

“The same thing was true with Ebenezer Scrooge,” he told me, as a nurse brought him three pills.

For all the morbidity of existential psychotherapy, it is deeply life-affirming. Change is always possible. Intimacy can be freeing. Existence is precious.

“I hate the idea of leaving this world, this wonderful life,”

Yalom said, praising a metaphor devised by the scientist Richard Dawkins to illustrate the fleeting nature of existence. Imagine that the present moment is a spotlight moving its way across a ruler that shows the billions of years the universe has been around. Everything to the left of the area lit by the spotlight is over; to the right is the uncertain future. The chances of us being in the spotlight at this particular moment—of being alive—are minuscule. And yet here we are.

Yalom’s apprehension about death is allayed by his sense that he has lived well.

“As I look back at my life, I have been an overachiever, and I have few regrets,” he said quietly. Still, he continued, people have “an inbuilt impulse to want to survive, to live.” He paused. “I hate to see life go.”