We’ll always have Paris

Just the other day someone asked me what’s my favorite movie. It’s never an easy question to answer, my claim can change from day to day, from season to season, my mood or the colour of the sky can be a decisive aspect to how I’ll defend or deny my choice. But if there’s one film that touches me deepest, that excites me and saddens me exquisitely with its sorrowful song, that film is Paris, Texas.

To my mind there isn’t another film that speaks so many certainties, that contains so much sad poetry, that subsumes such endless longing, that seeks such fervent truth, and that actually provides answers to questions we’ve all struggled to articulate. At its core, Paris, Texas makes an open-handed attempt to redeem us all, and it solely succeeds.

In 1984 director Wim Wenders (The American Friend, Wings of Desire, Buena Vista Social Club) working with a superb screenplay by L.M. Kit Carson and Sam Shepard, set out to the Mojave desert (and later, Huston, Texas and environs) to shoot what would become one of his seminal works and be a career milepost for all concerned.

Essentially a genre picture, Wenders love for road movies provided the template for what ultimately, I feel, is best described as a fable steeped in the American imagination and the archetypal aspirations therein.

Frequent Wenders cinematographer Robby Müller (also the go-to guru to Jim Jarmusch amongst others), in all his dream-like and wringing-wet with colour splendour, made for a clandestine partnership. Building on their previously established affection for Edward Hopper-like visuals (Alice in Cities and Kings of the Road offer superb examples of this), the world they created for Paris, Texas flickers with a ghostly fire.

Neon-lit interiors dance with unearthly delight as hotels, diners, peep-shows, and car parks sparkle like jewels. In Wenders’ vision, American cities exist in and out of time, but truthfully that’s where the story completes itself, its genesis is more sun-bleached and barren.

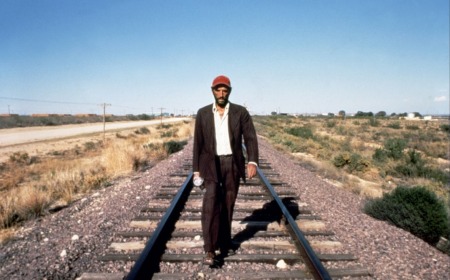

The first images we see in Paris, Texas is of a lone, mislaid figure stumbling through the desert, a red cap visible almost like a flare. An ersatz Moses, Travis wanders from the wastes, brought brazenly to life by the almost superhuman Harry Dean Stanton. So glorious is he in this role that a certain pop legacy was born (Scottish indie rock band Travis named themselves as an homage) to the accompaniment of Ry Cooder’s score.

Cooder, to his credit, provides the film with an epical nostalgic soundtrack, his slide guitar, inspired by Blind Willie Johnson, helped to punch up the yearning yen of our protagonist before he’d even uttered a word on the screen.

Nothing out there

It’s revealed rather briskly, that Travis has been gone for years, presumed dead, and nearly forgotten. His brother, Walt (Dean Stockwell, exceptional), comes to collect Travis from a rest stop where we learn more. Travis had a wife and a child. What’s become of them? And what of Travis? Where did he go for so long and why?

Rounding out the rest of the principle cast is Walt’s wife, Anne (Aurore Clément, deeply affecting), sweet as surrogate parents for Travis’ seven-year-old son, Hunter (Hunter Carson, the son of L.M. Kit Carson and Karen Black) and the radiant Nastassja Kinski as Travis’ estranged wife, Jane.

They’re all uniformly strong, not a weak link in the bunch. Carson, as Hunter, delivers one of the best performances by a child actor that I can think of. His attempts to grapple with grown-up feelings of loss and regret is shocking yet unquestionably real.

The family dynamic, and Paris, Texas gives us a few differing exemplifications of this, is very much shaped by Wender’s spiritual mentor, the versed Japanese director and screenwriter Yasujirō Ozu (Tokyo Story). One need look no further than Wenders’ 1985 documentary Tokyo-Ga to fully grasp the impact and ascendency Ozu had on him.

But as far as Paris, Texas is concerned, particularly the family politics, the spaces in between children and adults, the due order of the household dynamic, it certainly could only exist in a post-Ozu world. This is also distinct in the many low angle shots, almost as if they were coming from Hunter’s perspective, a play on Ozu’s patent “tatami shot”, where a subjective camera angle suggests the position of a person kneeling, as if in genuflection. It’s an understated but crushing move.

In a grand manner, Stanton, both father and prodigal son, dominates the film, though it’s not entirely his story, even though, as a lost soul hungry for restitution, we root for him. Kinski, who was never more graceful and at bay, also captures our affections.

That Travis would walk the desert wastes for her, grieve so greatly her fall from grace, that we can believe. Her scenes with Stanton provide the ne plus ultra of the film, enduring and endlessly profound. They are husband and wife and they are barely able to sense or even see one another. At this point in the film, it all seems too symbolic, too exact. But look deeper, if you dare.

What we talk about when we talk about love

It’s not my intention to give away any plot points, the first time I saw Paris, Texas I had no idea where each scene would lead and I wouldn’t deny such pleasures to anyone. But I will say that the film has so infatuated me that I’ve enthusiastically and with a full heart revisited it many times and will continue to do so. Not because it left me perplexed (perhaps as some of Wenders other films have), but because, like a favourite record from your favourite band, I’ve wanted to experience it all again. And, like a favourite record, it improves, it becomes more intimate, it fastens itself to you, and you to it.

Paris, Texas is about a couple, in one aspect, and the mysterious depths of a marriage. Male and female relations suggest, in Wender’s dream, a cultural disparity, and that’s an aching lyric of anguish and loss for the ages.

Shane Scott-Travis

Taste of Cinema