Roger Ebert was widely regarded as one of the most prolific and influential film critics of all time. As the first film critic to win both the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism and the first critic to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame his contribution to both the art of film criticism and the movie industry as a whole is still being recognised years after his death in 2013 after a long battle with cancer.

Not only was Ebert’s opinion highly respected and cherished by millions across the world but his endorsement of certain filmmakers could be seen as highly advantageous to their careers and extremely valuable to their status within the film industry as a whole. With so many people relying on Ebert to inform them on what artists were worth spending their money on to sample their work, when Ebert spoke highly of a certain director or screenwriter it was not to be ignored.

Ebert had numerous filmmakers that he favoured and frequently praised, either for the boldness of their filmmaking, the talent behind the camera or the passion they showed for their profession. He could single out certain director’s right at the start of their careers and spot their potential, envision the possible achievements and follow their careers until they flourished into masters of their craft.

This list will focus on those kind of examples. While there were many classic artists such as Hitchcock, Bergman and Kurosawa that Ebert regularly praised and held up as true artists, they were already established auteurs when Ebert began his career as a critic.

The list will focus on the filmmakers for whom Ebert praised before they were even a proven success, ones that Ebert used his reputation and status to endorse because he saw their potential and watched as they went on to achieve greatness.

15. Robert Zemeckis

I think it’s fair to say that Ebert could never have imagined how much he would grow to love Robert Zemeckis as a filmmaker based on his early efforts.

Despite enjoying the early directorial effort I Wanna Hold Your Hand Ebert was left disappointed by Used Cars, that he felt lakced any real comedic instinct despite being “high on kinetic structure”. Zemeckis’ next film faired better as Ebert awarded three stars to the romantic, comedy, adventure Romancing the Stone that he regarded as both “silly” and “high spirited”.

All of Ebert’s reviews highlighted the energy within Zemeckis’ direction but felt that he needed a story to match them. He found that in 1985 with Back to the Future, an instant favourite that Ebert praised both for its fantastic script that “like all great screenplays, starts with a point of common interest, in this case being what our parents were like at our age”.

But beyond just the comedy and science fiction elements that many critics have centred on, Ebert admired the humanism behind the film, comparing it to the likes of Frank Capra.

Then in 1988 Ebert awarded four stars to Zemeckis’ Who Framed Roger Rabbit. The original review is probably one of the most flamboyant expressions of praise Ebert gave to any film, with a sense of utter joy and wonder to support a technically remarkable film.

Ebert praised the film emphatically, regarding it as an “immense challenge” in being both “a good movie that also invents new technology at the same time” as well as simply an expression and “celebration of the fun you can have with a movie camera”.

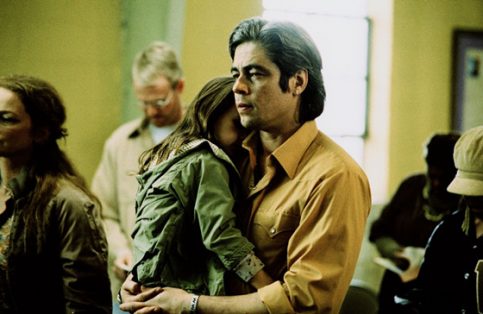

14. Alejandro Inarritu

When the Mexican director first appeared on the scene with his debut feature Amores Perros, he secured both a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and as glowing recommendation from Ebert, who awarded the film three and a half stars out of four. He compared Inarritu’s work to the likes of Arturo Ripstein and Alejandro Jodorowsky and labelled the newcomer as “a born filmmaker”.

Inarritu’s use of a nonlinear narrative was something he would revisit frequently throughout his career, especially in his next two films that combined with Amores Perros would form his unofficial Trilogy of Death. However Ebert was less enthusiastic about the director’s next feature, 21 Grams.

While he still awarded it a commendable three stars Ebert felt that it was merely treading ground that had already been explored and questioned whether the narrative structure was necessary to the film, arguing “Is this approach better than telling the same story from beginning to end?” and stating that “an unnecessary screen technique had been placed between the story and the audience”. He would award the same grade to Innaritu’s 2010 effort Biutiful, which he called a film of “great intimacy”.

However he still referred to Inarritu as “an unreasonably talented filmmaker” and this was reflected in Ebert’s review of his next film, Babel. It received a full four star rating, was placed at the number nine spot on Ebert’s best of 2006 list and was included in his Great Movies collection the following year.

Not only was Inarritu himself praised as being “in full command of his own technique”, but his fellow Mexican directors Alfonso Cuaron and Guilmero Del Toro were referred to as “a great generation of filmmakers” and being “among the adornments of recent cinema”.

13. Jeff Nichols

Despite appearing as a prominent voice in the film industry very late in Ebert’s life and career, the critic instantly praised Nichols as a talent to watch out for and endorsed his work heavily. He invited both of the director’s features to participate in his annual film festival Ebertfest, encouraged audiences to see them and even chastised the Academy Awards when they refused to acknowledge or nominate either film in any category.

“Few films are so observant about how we relate with one another”. That is what Ebert wrote of Jeff Nichols’ 2008 film Shotgun Stories, a film that portrays the scars of conflicts and violence and one that Ebert commended as “sympathetic” as well as showing an appreciation for the fact that the film “avoids the obvious and shows a deep understanding of the lives and minds of ordinary young people in a skirmish of the class war”.

Nichols’ next film, Take Shelter, was released on 2011 and like Shotgun Stories it made an appearance on Ebert’s annual best of the year list and also received another four star review.

He praised Nichols’ direction as “masterful filmmaking” as well as Michael Shannon’s performance that he felt was one of the best performances of the year and a lack of an Oscar nomination showed “an indication of the fairly narrow range of films it considers.”

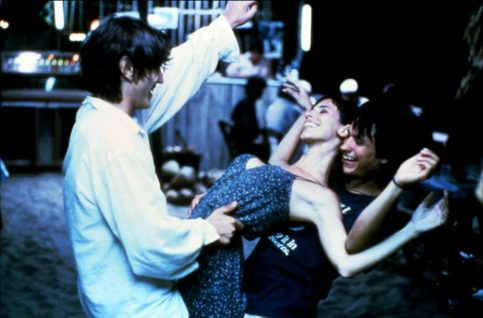

12. Alfonso Cuaron

Emerging in 1995 with his first feature film, A Little Princess, Ebert was immediately captivated by Alfonso Cauron’s talent behind the camera. The film focuses on a young girl who is relegated to a life of servitude in a New York City boarding school by the headmistress after receiving news that her father was killed in combat.

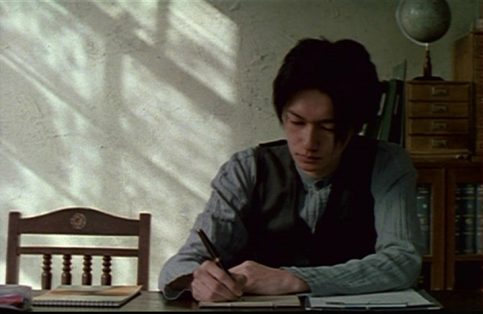

Despite being highly acclaimed and earning two Oscar nominations the film struggled at the box office due to poor promotion by its distributor, but that didn’t stop Ebert calling it a film with “a sense of wonder”. Ebert expressed a similar enthusiasm for Cuaron’s next film, an adaptation of Great Expectations that, despite not living up to previous adaptations of the Dickens novel was labelled as “an overlooked masterpiece.”

With Cuaron’s next film however, there was no “overlooked” to accompany its position as a masterpiece. Y Tu Mama Tambien was a coming of age, romantic, dramatic road movie that seemed to defy any obvious categorisation and this was noticed by Ebert, who praised the film as being about much more than “just two boys”, as having more to do with “two countries” and “two states of life”. He regarded it as “One of those movies where after that summer, nothing would ever be the same again”.

Ebert even defended the film against the MPAA for their treatment of the film due to its depiction of sex and drugs and questioned why other professionals in the industry were not as outraged as he was. “Why do serious film people not rise up in rage and tear down the rating system that infantilizes their work?”

When Cuaron made the transition to big budget movie making with Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in 2004 Ebert continued to show support, praising it as “the best looking in the entire franchise”. Then his next big studio film from 2006, Children of Men, was also hailed as a modern masterpiece that Ebert ranked as the third best film of that year.

He likened its visual storytelling to Metropolis and Nosferatu and regarded as the fulfilment of Cauron’s earlier career promise, “Here is certainly a world ending not with a bang but a whimper, and the film serves as a cautionary warning”.

11. Charlie Kaufman

Having been singled out by many as one of the finest screenwriters of the 21st century and well on his way to becoming one of the finest of all time, Charlie Kaufman was a recular recipient of Ebert’s praise from his screenwriting debut of Being John Malkovich, which was named by Ebert as the best film of 1999 to his directorial debut Synechdoche, New York that Ebert also named the best film of its year as well as the best film of the entire decade.

An experimental meta comedy from an untested screenwriter and director was probably not up for much consideration prior to its release in a year stuffed with high budget blockbusters and prestige studio pictures.

However it ended up topping Ebert’s annual list, as he praised Being John Malkovich as “endlessly imaginative” full of “dazzling inventions, twists and wicked paradoxes”. He also suggested that the Academy members “need portals in their brains” as it was the alternative to the film being nominated for Best Picture, of which Ebert felt it was fully deserving but ultimately failed to secure the nomination.

Ebert would go on to award another four stars to Kaufman’s next collaboration with Spike Jonze, Adaptation. He found it to be “wildly inventive” and “wickedly playful”.

Despite only awarding three and a half stars to Kaufman’s next screenplay, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Ebert revised that opinion in 2010 as he included it amongst the Great Movies collection (automatically giving it a four star rating) and praising Kaufman as “the most gifted screenwriter of the 2000s” and a writer who is “concerned above all with the process of thought and memory”.

But of all the films Kaufman penned, the one that Roger offered the most praise to was his directorial debut, Synechdoche, New York of which Ebert wrote that it was “a film with the richness of great fiction,” that dealt with “the mind, and only one plot, how the mind negotiates with reality, fantasy, hallucination, desire and dreams”. He would go on to name it the best film of the decade, and one of the greatest he had ever seen.

10. Jane Campion

The New Zealand born filmmaker was not only the second of four women to be nominated for Best Director but also the first woman ever to receive the Palme d’Or and from her 1989 film Sweetie Ebert marked Jane Campion out as a filmmaker to watch.

The critic awarded three and a half stars to Campion’s bizarre family drama, admitting that he found the film “difficult” upon his first viewing and suggests that many viewers will have a similar experience. But ultimately he found the film to be a “strange” and “curious experience”.

Campion’s next film came in 1991 and as far as Ebert was concerned An Angel At My Table was a step in the right direction, as it received the full four star rating with Ebert writing that “I found myself drawn in with a rare intensity”.

Once again he employed the use of the word “strange” to describe the film, signalling that Campion had already established a distinctive style that would go on to define her filmmaking career. Furthermore, unlike her previous effort Ebert found this film to be captivating from the first watch that only became “more engrossing”.

“The Piano is as peculiar and haunting as any film I’ve ever seen” were the words that opened Ebert’s review of Campion’s 1993, Palme d’Or winning masterclass. He praised not only the construction of the film and its world class performances, but also the way in which Campion displayed an understanding of her own story. Not only that but Ebert expressed a deep gratification for the films method of creating “a universe of feeling” beyond just its performances and screenplay.

Campion’s next few films never quite lived up to the promise Ebert had highlighted here though. His three star review of The Portrait of a Lady stated that despite his admiration “too much is glossed over, or implied”.

Then her next two films fell a step further with Holy Smoke and In the Cut both received two and a half stars, but as opposed to dismissing Campion as an unfulfilled promise he reflected on how she, like other directors, was still being innovative and experimental, even if these ideas were not as fulfilling at least Campion was moving forward as opposed to recycling the same ideas.

Her 2009 effort was a return to form with Bright Star, as Ebert awarded the film three and a half stars, praising it as both “beautiful and wistful”.

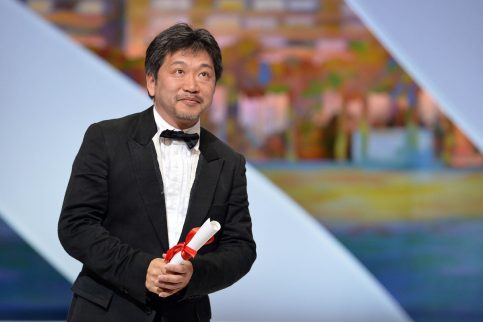

9. Hirokazu Kore Eda

Ebert was a great admirer of delicate cinema, directing that focussed more on the poignant details of life and the human experience and conveyed them through the use of cinema.

It was one of the many reasons he hailed Yasujiro Ozu as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Hirokazu Kore Eda shared some of these traits and worked along a similar style of directing, something that Ebert noted in his directorial debut Maborosi, a film that he described as one of “astonishing beauty and sadness”.

Having earned one four star review from Ebert, Kore Eda secured a second one with After Life in 1999. The film was great enough for him to deem Kore Eda as “one of the great humanists of cinema” and forced him to ponder the values of memories due to how the film not only evoked great emotions but also “deserved them” and compared it to the usual Hollywood equivalent that would discolour such a story through “vulgar, paint by the numbers sentimentality”. It earned comparisons to Bergman and Kurosawa, instantly marking Kore Eda as a filmmaker to watch.

It took Kore Eda six years to direct a follow up and 2005’s Nobody Knows received a three and a half star review from Ebert which would remain a career low for the director and I think we can safely say that is an impressive accomplishment.

He singled Kore Eda out as “the most gifted of Japanese directors” working today and he cemented that status with his 2009 film Still Walking in which he was back to a four star rating and still receiving high praise. Ebert admired the emotions Kore Eda was able to evoke as well as how “he sees intensely and tenderly into his characters”.

8. Guilmero Del Toro

Right from the start of his career as a filmmaker It was Guilmero De Toro’s unique and “genuine visual sense” that marked him out to Ebert as a director to watch and one he would admire for several years. One of Del Toro’s earliest films, Mimic, was one that Ebert regarded as being “Surprisingly frightening” and Del Toro’s status as “a master of dark atmosphere” was cemented with his next feature, 2001’s The Devil’s Backbone.

When Del Toro made the transition to blockbuster filmmaking Ebert was impressed at how he had retained his unique visual stylistics and personal connection with each film. He praised Blade 2 as a “brilliant vomitorium of viscera” that had been fuelled by the filmmakers imagination rather than seen as purely a commercial machine.

The same could be said for Del Toro’s other forays into comic book movies when he released Hellboy in 2004 and its sequel Hellboy: The Golden Army. Ebert admired the imagination behind both films, the set design, atmosphere and how it treated ach character with dignity and respect after strongly establishing them. In the end he awarded all three films with the rating of three and a half stars.

Then came what is still regarded by almost everyone as the director’s undisputed masterpiece, Pan’s Labyrinth. He praised it as “one of the greatest of all fantasy films” but admired how Del Toro was able to ground it “within the realities of war”. He adored the potential to interpret and reinterpret the film, as either an out of body experience or an internal escape from the horrors of war.

Less than a year after the films debut it was included in Ebert’s Great Movies collection, becoming the first film to break his unofficial rule of allowing ten years to pass before being included due to both Ebert’s failing health and the strength of Del Toro’s masterpiece.

7. Sofia Coppola

Despite carrying an immense heritage with Francis Ford Coppola as her father, Sofia Coppola instantly made an impact on the film industry with her directorial debut The Virgin Suicides. Ebert awarded the film three and a half stars out of four and instantly saw the potential in Coppola’s writing and direction that inspired her viewers to see with a new perspective and fresh insight into the world Coppola’s characters occupy.

Like many critics Ebert was astounded by Coppola’s next work, her widely acclaimed 2003 drama Lost in Translation. Ebert deemed the film to be “smart and thoughtful” in his four star review and in the end simply summarised that he “loved this movie”.

Not only has that but like everyone else who has seen the film Ebert pondered what could have been said in that fateful, final whisper. But he also concludes that “We shouldn’t be allowed to hear it. It’s between them, and by this point in the movie, they’ve become real enough to deserve their privacy.”

In 2010 Ebert added it to the Great Movies collection, continuing the same conversation and coming to a similar conclusion. He still admired the staying power of the film and its emotive gratitude towards its own characters that not only makes the audience empathise with them, but turns them into real and complex people.

Coppola’s 2005 film Marie Antoinette remains her most divisive yet Ebert thought otherwise, awarding the film another full four stars. Not only did Ebert admire the film itself but he also reflected upon Coppola’s authorship and how consistent themes throughout her films were allowing them to distinguish her as a unique and talented filmmaker with a distinctive style.

The four star trend would continue into Coppola’s next film. Released in 2010, Somewhere inspired Ebert to write that “Coppola is a fascinating director”. He respected the way in which she once again allowed audiences to confront an issue in an entirely different way and how as an auteur “She sees, and we see exactly what she sees.”

6. Ramin Bahrani

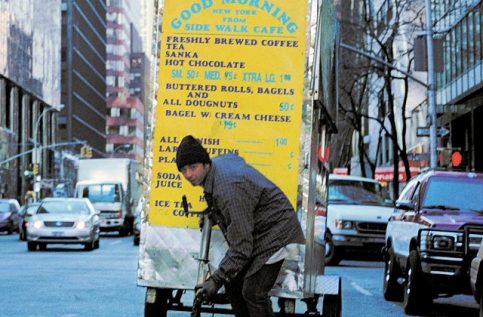

For all of the high profile directors to emerge during the 2000s, it was this American Iranian director of such films as Man Push Cart, Chop Shop and Goodbye Solo that Ebert labelled “the director of the decade”.

Of Bahrani’s first film Ebert wrote that it “embodies everything of Italian Neo-realism” and was astonished by its true and real depiction of immigrant life within New York City. He commented that even the title itself “encapsulates human survival at its most fundamental economic level”.

If Ebert spoke highly of Man Push Cart then he was even more impressed with Bahrani’s follow up, Chop Shop. Not only did it also receive a full four star rating but it was also included in the Great Movies collection less than a year after its release and was named the 6th best movie of the decade by Ebert in 2009.

He regarded the film as “a coming of age story” but also a hard fought lesson of life on the streets and once again centred on New York City, maintaining a consistent theme that would carry on throughout all of Bahrani’s films.

Next came Goodbye Solo and yet another four star review, during which Ebert stated that “Bahrani is the new great American director. He never steps wrong”.

His review concentrates on the relationship between the actors and the directors and how Goodbye Solo stayed true to Bahrani’s consistent theme that continued to permeate his films, in that they are “about outsiders looking into America” and the method in which the director went about summarising this theme collective consciousness represented by unique yet strangely familiar events.

However, Bahrani’s next film diverged from this theme, something Ebert immediately noticed in yet another four star review written in 2013, which notes how this film deconstructs American tropes and icons in a very effective manner.

Ebert noted the relative simplicity of the film but also how that simplicity can merely be an illusion for the more complex and avoided being focussed on just a single topic. “this film doesn’t wrap things up in a tidy package. It is a great film about an American moral crisis.”

5. Quentin Tarantino

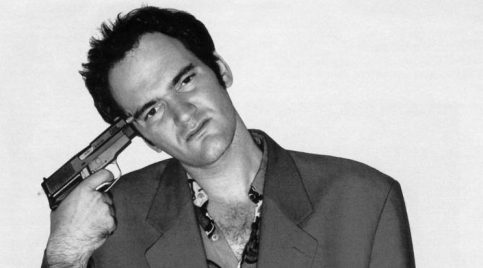

In 1992 it would seem odd to think that Quentin Tarantino would go on to become one of Ebert’s most championed filmmakers, especially given the rather lacklustre response from Ebert to his otherwise highly acclaimed thriller Reservoir Dogs.

Ebert conversely awarded the film just two and a half stars out of four, praising the dialogue, style and performances but ultimately felt the film lacked depth and humanity, that none of the characters evolved beyond their initial archetype.

Ebert was wise enough to spot potential however, and noted at the end of his review that “Now we know Quentin Tarantino can make a movie like Reservoir Dogs, we know he can make a better one”.

Tarantino did indeed deliver on that promise as his next film was named by Ebert was the second best and most influential film of the entire decade, Pulp Fiction. He praised the non linear storyline, the nature of Tarantino’s writing from the wonderful stylistics to the “seemingly irreverent dialogue” that “builds characters, plotlines and the foundation of the film itself”.

By the time he added Pulp Fiction to his Great Movies collection Ebert had also awarded another four stars to Tarantino’s next film, Jackie Brown. While some see it as a step down Ebert found it to be “perfectly written, timed and played”. He marvelled at Tarantino’s ability to create such empathetic characters, ones that he “wanted to see live, talk, deceive and scheme for hours upon hours.”

The same high rating would continue for Tarantino’s most widely known property, the Kill Bill saga. Ebert awarded both Volume 1 and Volume 2 a full four stars, praising Tarantino’s direction in the first instalment as “brilliantly in command of his technique” and while he admitted the substance was somewhat lacking, the style was enough to compensate for it.

However if Ebert was looking for substance then Volume 2 delivered it for him succeeding in “deepening my appreciation of the saga as a whole”. Ebert would go on to name the collection as one of the best films of the decade just as he had done with Pup Fiction beforehand.

By the time Ingloruous Basterds appeared in 2009 Eberg had already deemed Tarantino to be “the most brilliantly oddball director of his generation” and he reaffirmed that statement when he awarded another four stars to the directors “audacious war movie”.

The same could be said for his contemplation on the director’s 2012 western Django Unchained. Though Ebert never wrote an official review due to ill health, he felt the movie warranted an in depth blog post during which he praised it as “brilliant entertainment”.

4. Steven Spielberg

Though it’s debatable whether a director as popular as Steven Spielberg ever needed a critics endorsement to secure their place as an auteur, Spielberg was a frequent favourite of Ebert, which was particularly obvious when the critic defended Spielberg against those who felt he was merely another commercially interested filmmaker.

From his legendary blockbuster break out back in 1975, Jaws, which Ebert awarded four stars and compared to the thrillers of Hitchcock or Freidkin, while calling it “masterfully suspenseful” and admired its use of strong characters with whom the audience builds a connection with to establish that suspense.

What followed was decade after decade of praise directed towards Spielberg, (with a few notable exceptions in the form of 1941, Always and Hook) from his 1977 passion project Close Encounters of the Third Kind which also earned a four star review and a place on Ebert’s annual best of the year list. He called it an “astonishing achievement, capturing the feeling of awe and wonder we have when considering the likelihood of life beyond the Earth”.

Ebert gave similar praise to Spielberg’s action extravaganza Raiders of the Lost Ark, stating that the film was “an out of body experience, a movie of glorious imagination and break neck speed that grabs you in the first shot, hurtles you through a series of incredible adventures, and deposits you back in reality two hours later — breathless, dizzy, wrung-out, and with a silly grin on your face”.

Raiders of the Lost Ark was one of two Spielberg films to earn a place among Ebert’s list of the top ten films of the 1980s, along with E.T: The Extra-terrestrial. It received the full four stars back in 1982 and would go on to be included in Ebert’s Great Movie collection as well. Not only that, but when Ebert himself was criticised for labelling Spielberg as a great director, his response was “I do not believe the man who made E.T could be labelled as anything other than great”.

When Spielberg switched to more dramatic works Ebert remained just as supporting and continued to give praise to his films. The Colour Purple and Schindler’s List both received the full four star rating, were named the best film of the year they came out and received a Great Movie essay of their own.

One that did not receive the same honour was Saving Private Ryan, but that did not stop Ebert once again awarding Spielberg four stars and praising the director’s war epic as “astonishingly powerful”.

This trend continued into the 2000s with Minority Report also gaining the coveted four star review and being named the best film of 2002, as well as a place among Ebert’s favourite films of the decade. The same can be said for Munich, A.I: Artificial Intelligence (which even earned another Great Movie essay) right up to the last Spielberg film Ebert reviewed, Lincoln, with yet another four star review and spot on the annual top ten list.

3. Terrance Malick

By this point in his career Terrance Malick almost carries a mythical quality to him, as if his movies can transcend one simple interpretation and always represent far more. Ebert encountered Malick at the same point the rest of the world did with his 1973 directorial debut Badlands.

At the time he awarded it four stars and was impressed by its treatment of its own characters “They are strange people, as were their real-life models….They were just two dumb kids who got into a thing and didn’t have the sense to stop”.

Ebert was also impressed by the visual aesthetic of Badlands, but he was even more impressed by the cinematography of Malick’s next film Days of Heaven, which he called “one of the most beautiful films ever made” in another four star review. Unlike Malick’s other work Days of Heaven was not widely acclaimed and left many critics divided. But Ebert stood by his high praise and eventually added the film to his Great Movies collection along with Badlands.

After a long hiatus Malick returned with his third film, The Thin Red Line and despite being singled out by many as Malick’s greatest film Ebert was less enthusiastic, awarding it three stars.

For the first time he felt that Malick’s style was not synchronised with the story he was trying to tell, stating that there was a sense of disconnect by the fact that “The actors in The Thin Red Line are making one movie, and the director is making another.”

However Malick was once again receiving the maximum amount of praise with his 2005 film The New World. Evert admired the way Malick went about “stripping all the fancy and lore from the story of Pochahintas and imagines how new and strange these people must have seemed to one another”.

He praised Malick as “a visionary” who handled his subject matter with “with almost trembling tact” and praised his ability to focus more on emotions than anything else, bringing forth the feelings at the centre of the film.

In 2011 Malick returned with his experimental drama, The Tree of Life. Upon its release it proved to be a divisive project, but Ebert awarded it yet another four stars in his review. One of the opening lines of that review compared the films boldness of vision to Kubrick’s 2001, and then went on to praise the director’s “fierce evocation of human feeling”.

Not only did Ebert include the film on his annual best of the year list but he went a step further, as the following year the Sight and Sound critics plot required the world’s leading film critics and scholars to select their personal picks for the ten greatest films ever made. Ebert’s choice was the recent but deeply powerful film by Malick, The Tree of Life, a movie he selected for “it’s breath taking scope, but also its humane centre”.

Malick’s next film was not only the last film from the director that Ebert would review, but it was also the last film the famed critic would ever review. In one of his most poignant reviews Ebert addresses those who left the film unsatisfied, and felt that the film. He wrote that “I understand that, and I think Terrence Malick does, too. But here he has attempted to reach more deeply than that: to reach beneath the surface, and find the soul in need”. A fitting way for Ebert to leave his loyal readers and depart.

2. Werner Herzog

From his first review of a Herzog film, the German director was already cemented as one of Ebert’s favourite directors of all time, due in no small part to the fact that he would place Aguirre, the Wrath of God on his Sight and Sound selection of the ten greatest movies ever made.

In his original review he wrote that “Herzog’s other films sometimes speak unclearly; this one speaks in blunt, unforgiving despair”, he regarded it as a horrifying and obsessive film, one that was made all the more disturbing due to being based on fact. Ebert praised the “bizarre and affecting” images of the film, the gradual onset of madness and its “frightening intensity”.

Aguirre was one of the first films to be added to Ebert’s Great Movies collection and would become one of many from Herzog that found a place there. Another was Herzog’s 1974 picture The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, and wrote that “In Herzog the line between fact and fiction is a shifting one. He cares not for accuracy but for effect, for a transcendent ecstasy”, proving that the directors films had a distinct and profound effect on the critic to draw such praise from him.

The same could be said for Herzog’s next film, which received a further full stars and became the eventual recipient of another Great Movies Essay, in which Ebert wrote that “From it I get a feeling that evokes my gloom as I see a world sinking into self-destruction”. On each occasion Herzog’s films created a haunting and impactful effect on Ebert that clearly stayed with the critic long after the credits had finished rolling.

Herzog’s next two films were to receive the exact same honour. “One of the oddest films ever made” was what Ebert wrote about 1977’s Stroszek, but it was clear Ebert had not only become accustomed to Herzog’s unique filmmaking sensibilities but it was one of the aspects he most admired about the director, “Who else but Werner Herzog would make a film about a retarded ex-prisoner, a little old man and a prostitute, who leave Germany to begin a new life in a house trailer in Wisconsin?”

Ebert expressed a different kind of admiration for Herzog’s next film, one that adapted the story of Nosferatu the Vampyre, calling it “rich, heavy, deep”, he admired its beauty just as much as its ability to invoke terror and expressed that it was the “most evocative series of images centred around a vampire that I have seen since F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu”. He concluded that the film could not be confined to a single genre, that it was “about dread itself” and was undefinable.

During the production of Herzog’s next film, when Ebert saw set images he feared the director had embarked upon a suicide mission. Before the film was even complete Ebert contemplated that if the project was completed and Herzog was able to survive the ordeal “one of the greatest accomplishments in the history of filmmaking”.

When he saw the film itself, despite acknowledging some of its flaws, Ebert regarded it as “a movie in the great tradition of grandiose cinematic visions”. Despite “not quite reaching perfection” Ebert still awarded the film four stars, “as a document of a quest and a dream, and as the record of man’s audacity and foolish, visionary heroism, there has never been another movie like it”.

At the turn of the century Herzog made the move to crafting more documentary features than dramatic ones. But Ebert admired his ability to make his non-fiction works as riveting as his staged ones, giving positive reviews to My Best Friend, Invincible, Grizzly Man and Encounters at the End of the World.

But when he made a return to narrative features, Ebert was still just as enthusiastic over Herzog’s work, awarding three and a half stars to Rescue Dawn in 2007 and another four star rating to the director’s divisive crime drama, Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call – New Orleans.

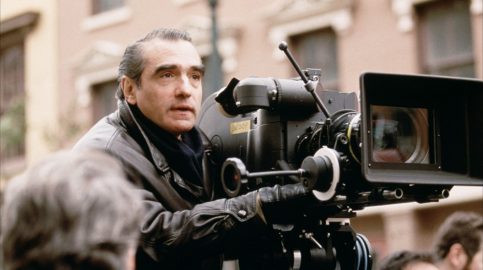

1. Martin Scorsese

In 1967 Roger Ebert was a relatively inexperienced film critic, but having just seen an early feature at the Chicago International Film Festival of a recent independent movie named I Call First, he chose to award it three and a half stars out of four.

Two years later when the film had finally been given a wide release and the title had been changed to Who’s That Knocking On My Door Ebert admitted he may have been over enthusiastic but was still positive about the film, and awarded it the same rating.

He also focussed on its director, for whom the feature had been a debut and said that “It is possible that with more experience and maturity Scorsese will direct more polished, finished films.” That was, to say the least, an inspired piece of insight.

Despite a relatively slow start with his next feature, a low budget exploitation movie called Boxcar Bertha, Martin Scorsese would go on to become one of Ebert’s most beloved and cherished filmmakers of all time, one that he had endorsed right at the start of his career and continued to do so right up to the critics death in 2013.

In 1973 Ebert awarded the director his first four star rating when he released the independent crime drama, Mean Streets, writing that “In countless ways, right down to the detail of modern TV crime shows, Mean Streets is one of the source points of modern movies.”

Ebert was similarly enthusiastic about Scorsese’s next feature titled Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. He cited it as “one of the most perceptive, funny, occasionally painful portraits of an American woman I’ve seen”. But this proved to be just a small dose of the filmmaker’s full potential as just a year later he released the defining masterpiece Taxi Driver.

A film that Ebert showed particular insight and poignancy towards when reviewing it, commenting on the films deeper meaning and themes, what it said about the human condition and the way it handled its own tortured characters.

Scorsese’s next masterpiece came in 1980, another collaboration with Robert De Niro, the boxing biopic Raging Bull. Ebert called it “the culmination of Scorsese’s earlier promise” and an instant classic. Both he and his At the Movies co-host Gene Siskel deemed it to be the greatest movie of the decade, and when composing his list of the ten greatest movies ever made Ebert was sure to include Raging Bull.

Ebert gave similarly glowing reviews to other Scorsese features of the 1980s including After Hours and The Last Temptation of Christ. They both ended up on Ebert’s annual list as well as a place within the Great Movies Collection. By this point Ebert considered Scorsese to be a staple of modern American filmmaking and that status would only increase throughout the next decade.

In 1990 Scorsese released his widely acclaimed crime drama, Goodfellas. Ebert names it the best film of that year and among the top three of the decade. He wrote that “No finer film has ever been made about organized crime – not even The Godfather.” Ebert would award another four star rating to Scorsese’s 1993 period piece, The Age of Innocence, an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Edith Wharton.

Ebert noted how the film was not as far a cry away from Scorsese’s other work as some critics might have thought, “”The story told here is brutal and bloody, the story of a man’s passion crushed, his heart defeated. Yet it is also much more, and the last scene of the film, which pulls everything together, is almost unbearably poignant.”

After two more four star reviews that were awarded to Casino and Bringing Out the Dead, as well as a string of other positive reviews to Scorsese’s various films of the 1990s Ebert continued to praise the director into the next decade. His highly admirable review of The Departed, the film that would finally give Scorsese his long awaited Best Director Oscar, stated that “This movie is like an examination of conscience and identity”.

As well as awarding a further four stars to the director’s acclaimed documentary No Direction Home, in 2008 Ebert would release a book simply titled, Scorsese. It featured reviews and revisions of the acclaimed directors work as well as a number of interviews with him. As the only director to have an entire book by Ebert, devoted solely to his career it marks him as one of Ebert’s most championed director.

Joshua Price

You must be logged in to post a comment Login