Even if you’re a newcomer to The Beatles’ legacy, it’s hard to imagine a time when Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Bandwasn’t part of the popular culture lexicon.

But even after The Beatles gave up touring for good in August 1966 — frustrated by the constant screaming of the teenage girls who populated their stadium-sized shows, and worn down by the threat of violence that seemed to follow them around, particularly after the brouhaha following John Lennon’s observations that the group meant more to their fans than religion — they were still considered little more than a passing fad.

Sure, the latest single or album caused great fervor among the faithful, but it was hardly the “event” we might consider it today.

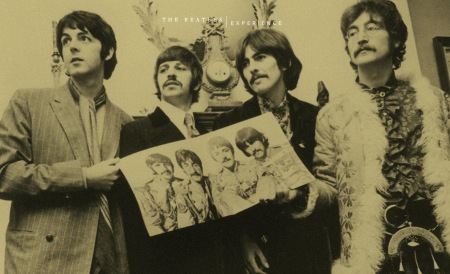

How bold it was, then, as Paul McCartney flew back from a visit to the West Coast of the United States to England, for him to concoct the idea of The Beatles assuming alternate personalities as they undertook their next project. The idea he presented to his bandmates upon his return was for them to think of themselves as another band. That way they could write and play in any manner they chose, unshackled by any preconceived notions of who those other guys — The Beatles — might be. And boy did they.

By the opening moments alone — from an anonymous orchestra tuning up, through McCartney’s exaltations to the listener to join in the cheering revelry — even this relatively straightforward rock and roll number was distinctly fresh and new and unlike anything that had come before it.

That it immediately segued into a number by Billy Sheers (drummer Ringo Starr in disguise) and then again into the dreamlike, Lewis Carroll-inspired world of “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds,” signaled that this miles beyond what fans had encountered on the groundbreaking Revolver just one year before. No, this was a different animal altogether.

Today The Beatles are part of our collective DNA, but in 1967 even the songs that followed — “Getting Better” and “She’s Leaving Home” — which had perhaps more of the feel of the natural successors to “Good Day Sunshine” and “Eleanor Rigby” from Revolver, must have seemed like messages from another planet.

They were followed by a Victorian fairground pastiche, a dose of Indian mysticism and the odd juxtaposition of an old knees up mixed with melancholia, typifying just how far The Beatles had come as creative artists, not to mention how far they were willing to push their audience.

Rounding out the album with the sprightly McCartney story, “Lovely Rita,” and Lennon reportage, “Good Morning Good Morning,” Sgt. Pepper is wound down in grand style with the harder-rocking companion piece to the title song — and perhaps the greatest Lennon-McCartney co-write of them all — the peerless “A Day In The Life.”

Coming out of the dreamscape created by Lennon’s otherworldly voice and double orchestral crescendo, and ending on the crash of multi-tracked pianos, the album jars the listener back to the real world with the “Inner Groove,” a hidden outro containing a snippet of an Abbey Road party the band cooked up to allay any fears they become too self-serious, and Sgt. Pepper is over.

To dismiss this work with today’s ears, without acknowledging the scale and scope of the craft The Beatles had developed since the days of “Love Me Do,” is a mistake.

No artist before or since has climbed so high, and certainly not in the span of just five years. Sure, they went on to make better albums, but perhaps we take Sgt. Pepper for granted for the very reason that it’s had such palpable influence, or that it is a part of such an astonishing body of work. But we shouldn’t. It was a masterpiece on its release in June 1967, and it has stood the test of time. It’s a crowning achievement, even for The Beatles.

Remarkably, The Beatles weren’t finished by a long stretch. By the day after Christmas 1967 they had a self-produced TV film on the air and (in the U.S., at least) an accompanying album.

Magical Mystery Tour may feel like the kid brother to the towering Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but consider its contents and you’ll realize that there’s not an ounce of filler among its tracklist.

And besides, any album that includes “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “Penny Lane,” “I Am The Walrus” and “All You Need Is Love” is surely one that deserves a place of pride in The Beatles canon.

As the rest of the pack were just getting comfy in their psychedelic trappings, The Beatles were about to leave it all behind. Their manager and rudder, Brian Epstein, had died unexpectedly during the summer of ’67, just after they’d been introduced to the benefits of Transcendental Meditation by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

At their collective core The Beatles were just four Liverpool lads who’d been thrust into the global spotlight as no one had ever been before. No matter where they went they were besieged. So in the wake of Epstein’s death, the Maharishi’s invitation to visit his ashram in the picturesque Himalayas was just what they needed.

While the trip ended in nagging questions and recriminations, each of the group continued to practice mediation for the rest of their lives and, perhaps more significantly, they returned home in the spring of 1968 armed with loads of new songs.

They convened at George Harrison’s Surrey, England home in May to demo nearly 30 tunes, and began working on what has become known as the White Album at Abbey Road a week later.

Even in the company of Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde, the Stones’ Exile On Main Street and Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, The Beatles (as it’s properly titled) is probably the best and most remarkable double album in rock history. If the band was seen as being experimental on Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour, the White Album was yet another bold step in that direction — no small feat for the biggest band on the planet.

The White Album has been called sprawling, massive, perfect, and even discordant. It’s all of those things. But it’s also as perfect a testament to the collective creative genius of John, Paul, George and Ringo as was likely possible.

Quiet, intimate songs follow loud, brash songs, and vice versa. Cold Victorian numbers sit next to the Stockhausen-esque, and yet somehow it all fits together, forming a multi-dimensional whole. That there was discord within the group — Ringo Starr quit for a time and Lennon, McCartney and Harrison all worked in separate studios in Abbey Road — causes one to wonder if it was a necessary ingredient at this stage, or if they were just so good by this point that such squabbling didn’t matter.

Either way, the White Album is the one album by The Beatles that you should choose for a desert island.

Hot on the heels of the Christmas 1968 release of the White Album cameYellow Submarine in early 1969.

Featuring only one LP side of actual Beatles music (side two consisted of George Martin’s orchestral score for the Yellow Submarine film), it recycled its title track from Revolver and the anthem-cum-plot device “All You Need Is Love” alongside four new songs, mostly culled fromSgt. Pepper-era sessions, now a seeming lifetime ago.

They’re great, mind you, and there’s the bluesy Lennon rocker “Hey Bulldog” that’s the hidden gem of the bunch, but there’s not much more to be said for this album other than that it’s The Beatles, so of course it’s worth your time.

While the fans of The Beatles were digging into the grooves of Yellow Submarine in January 1969, the group was on a cold, damp soundstage in Twickenham, outside of London rehearsing songs for a live TV show and album.

Initially titled Get Back, and ultimately dubbed Let It Be, the project was a well-intentioned back-to-basic album. It would be produced without any of the indulgences, like multi-tracking or orchestration, the band had by now become synonymous with, and the songs would be quickly composed and played live, as a four-piece or with the help of keyboardist Billy Preston, their friend dating back to their formative years in Hamburg, Germany. Most lamentably, the whole process would be fully documented by a film crew.

But by the end of the month, after George Harrison had quit and returned, and the group had reconvened at their Apple Corps headquarters on Savile Row, London for an afternoon rooftop concert, followed by another in the building’s basement studio, the project had, for all intents and purposes, been abandoned. The world didn’t know it, but The Beatles had all but broken up.

Then, as the frosty English winter broke into glorious spring, producer George Martin got a call from Paul McCartney. Would he produce them again, just like the old days? Martin knew it might be the last time he’d ever take that call. Cautiously, given the failed Let It Be sessions, he said yes.

According to all involved, the sessions that would make up Abbey Roadwere indeed like old times.

Though John Lennon was absent more than he was there, owing to various trips with his new wife Yoko Ono, and a subsequent car crash in Scotland on one of their holidays, his indelible mark is still ever-present.

His songs and vocals are some of the best of his illustrious career, but so are the contributions of Paul McCartney — who masterminded the glorious medley on side two — and George Harrison, whose “Something” and “Here Comes The Sun” should be in anyone’s Beatles Top 10. Even Ringo Starr’s “Octopus’s Garden” is a career high, making Abbey Road, like so many of The Beatles’ albums, a greatest hits package in all but name.

While the album sounds different owing to Abbey Road Studio’s switch to a solid state mixing console, after putting its long-suffering tube equipment out to pasture, George Harrison’s inventive use of his new favorite gadget, a Moog synthesizer, and harmonies as unique and special today as they were 45 years ago, Abbey Road stands as the distillation of everything The Beatles had accomplished, and as a tease to what would never be again.

But there was still one missing piece in the massive jigsaw puzzle that is the band’s legacy to be put in place.

Save for a few attempts at mixing them into a coherent whole by various associates of the band, those January 1969 recordings had been sitting dormant. Then, in early 1970, with their Beatles days squarely behind them in all but the public’s eyes, John Lennon and George Harrison turned the languishing tapes over to producer Phil Spector, in the hopes that the fabled, if fading, legend could turn them into something worth releasing.

Let It Be was released in April 1970, and would stand as a career-defining album for any band that wasn’t named The Beatles.

Instead, it’s an album full of great songs that could hardly live up to any one of the albums that had preceded it, and certainly not Abbey Road. Still, it’s a snapshot of The Beatles, playing together as a live band, one last time, with joy and warmth and empathy, and the kind of shared musical language that no group had ever enjoyed before, or will likely ever share again.

In seven short years, from the opening “1-2-3-4” salvo on Please Please Me to John Lennon’s parting quip that he hoped the band “passed the audition” as Let It Be closer “Get Back” faded out, The Beatles had created a body of work beyond comparison.

It’s one that has survived the 45, the LP, reel-to-reel, 4-track, 8-track and cassette tapes, not to mention the CD and digital downloads. Now The Beatles belong to everyone, through digital streams courtesy of TIDAL. We hope you will enjoy the show.

Jeff Slate