If Baghdad today is a byword for inner-city decay and violence on an unspeakable scale, its foundation 1,250 years ago was a glorious milestone in the history of urban design. More than that, it was a landmark for civilisation, the birth of a city that would quickly become the cultural lodestar of the world.

Contrary to popular belief, Baghdad is old but not ancient. Founded in AD762 by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur “The Victorious” as the new seat of his Islamic empire, in Mesopotamian terms it is more arriviste than grande dame – an upstart compared to Nineveh, Ur and Babylon (seventh, fourth and third millennium BC respectively).

Baghdad is a mere baby, too, when compared with Uruk, another ancient Mesopotamian urban settlement, which lays claim to being one of the world’s earliest cities and which was, sometime around 3,200BC, the largest urban centre on earth with a population estimated at up to 80,000. Some think the Arabic title for Babylonia, al-Iraq, is derived from its name.

We know a huge amount about the city’s meticulous and inspired planning thanks to detailed records of its construction. We are told, for instance, that when Mansur was hunting for his new capital, sailing up and down the Tigris to find a suitable site, he was initially advised of the favourable location and climate by a community of Nestorian monks who long predated Muslims in the area.

According to the ninth-century Arab geographer and historian Yaqubi, author ofThe Book of Countries, its trade-friendly position on the Tigris close to the Euphrates gave it the potential to be “the crossroads of the universe”. This was a retrospective endorsement. By the time Yaqubi was writing, Baghdad, City of Peace, had already become the centre of the world, capital of the pre-eminent Dar al-Islam, home to pioneering scientists, astronomers, poets, mathematicians, musicians, historians, legalists and philosophers.

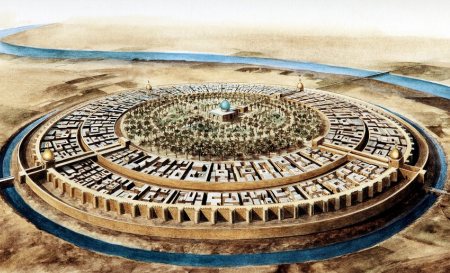

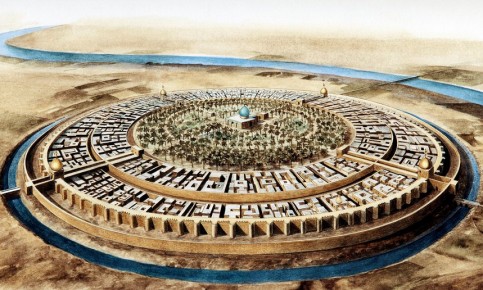

Once Mansur had agreed the site, it was time to embark on the design. Again we are told that this was entirely the caliph’s work. Under strict supervision he had workers trace the plans of his round city on the ground in lines of cinders. The perfect circle was a tribute to the geometric teachings of Euclid, whom he had studied and admired. He then walked through this ground-level plan, indicated his approval and ordered cotton balls soaked in naphtha (liquid petroleum) to be placed along the outlines and set alight to mark the position of the massively fortified double outer walls.

On 30 July 762, after the royal astrologers had declared this the most auspicious date for building work to begin, Mansur offered up a prayer to Allah, laid the ceremonial first brick and ordered the assembled workers to get cracking.

The scale of this great urban project is one of the most distinctive aspects of the story of Baghdad. With a circumference of four miles, the massive brick walls rising up from the banks of the Tigris were the defining signature of Mansur’s Round City. According to 11th-century scholar Al Khatib al Baghdadi – whose History of Baghdad is a mine of information on the construction of the city – each course consisted of 162,000 bricks for the first third of the wall’s height, 150,000 for the second third and 140,000 for the final section, bonded together with bundles of reeds. The outer wall was 80ft high, crowned with battlements and flanked by bastions. A deep moat ringed the outer wall perimeter.

The workforce itself was of a stupendous size. Thousands of architects and engineers, legal experts, surveyors and carpenters, blacksmiths, diggers and ordinary labourers were recruited from across the Abbasid empire. First they surveyed, measured and excavated the foundations. Then, using the sun-baked and kiln-fired bricks that had always been the main building material on the river-flooded Mesopotamian plains in the absence of stone quarries, they raised the fortress-like city walls brick by brick. This was by far the greatest construction project in the Islamic world: Yaqubi reckoned there were 100,000 workers involved.

The circular design was breathtakingly innovative. “They say that no other round city is known in all the regions of the world,” Khatib noted approvingly. Four equidistant gates pierced the outer walls where straight roads led to the centre of the city. The Kufa Gate to the south-west and the Basra Gate to the south-east both opened on to the Sarat canal – a key part of the network of waterways that drained the waters of the Euphrates into the Tigris and made this site so attractive. The Sham (Syrian) Gate to the north-west led to the main road on to Anbar, and across the desert wastes to Syria. To the north-east the Khorasan Gate lay close to the Tigris, leading to the bridge of boats across it.

For the great majority of the city’s life, a fluctuating number of these bridges, consisting of skiffs roped together and fastened to each bank, were one of the most picturesque signatures of Baghdad; no more permanent structure would be seen until the British arrived in the 20th century and laid an iron bridge across the Tigris.

A gatehouse rose above each of the four outer gates. Those above the entrances in the higher main wall offered commanding views over the city and the many miles of lush palm groves and emerald fields that fringed the waters of the Tigris. The large audience chamber at the top of the gatehouse above the Khorasan Gate was a particular favourite of Mansur as an afternoon retreat from the stultifying heat.

The four straight roads that ran towards the centre of the city from the outer gates were lined with vaulted arcades containing merchants’ shops and bazaars. Smaller streets ran off these four main arteries, giving access to a series of squares and houses; the limited space between the main wall and the inner wall answered to Mansur’s desire to maintain the heart of the city as a royal preserve.

The centre of Baghdad consisted of an immense central enclosure – perhaps 6,500 feet in diameter – with the royal precinct at its heart. The outer margins were reserved for the palaces of the caliph’s children, homes for the royal staff and servants, the caliph’s kitchens, barracks for the horse guard and other state offices. The very centre was empty except for the two finest buildings in the city: the Great Mosque and the caliph’s Golden Gate Palace, a classically Islamic expression of the union between temporal and spiritual authority. No one except Mansur, not even a gout-ridden uncle of the caliph who requested the privilege on grounds of ill-health, was permitted to ride in this central precinct.

One sympathises with this elderly uncle of the caliph. Unmoved by his protestations of decrepit limbs, Mansur said he could be carried into the central precinct on a litter, a mode of transport generally reserved for women. “I will be embarrassed by the people,” his uncle Isa said. “Is there anyone left you could be embarrassed by?” the caliph replied caustically.

Mansur’s palace was a remarkable building of 2,000 sq ft. Its most striking feature was the 130ft-high green dome above the main audience chamber, visible for miles around and surmounted by the figure of a horseman with a lance in his hand. Khatib claimed that the figure swivelled like a weathervane, thrusting his lance in the direction from which the caliph’s enemies would next appear. Mansur’s great mosque was Baghdad’s first. Encompassing a prodigious 1,000 sq ft, it paid dutiful respect to Allah while emphatically conveying the message that the Abbasids were his most powerful and illustrious servants on earth.

By 766 Mansur’s Round City was complete. The general verdict was that it was a triumph. The ninth-century essayist, polymath and polemicist al-Jahiz was unstinting in his praise. “I have seen the great cities, including those noted for their durable construction. I have seen such cities in the districts of Syria, in Byzantine territory, and in other provinces, but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defences than Al Zawra, that is to say the city of Abu Jafar al-Mansur.” What he particularly admired was the roundness of the city: “It is as though it is poured into a mould and cast.”

The last traces of Mansur’s Round City were demolished in the early 1870s when Midhat Pasha, the reformist Ottoman governor, tore down the venerable city walls in a fit of modernising zeal. Baghdadis have since grown used to being excluded from the centre of their resilient capital.

Just as they had been barred from the inner sanctum of the city under Mansur, so were their 20th-century counterparts excluded from the heart of Baghdad on pain of death 12 centuries later under Saddam Hussein. The heavily guarded district of Karadat Maryam, slightly south of the original Round City on the west bank, became the regime headquarters, the engine room of a giant machine carefully calibrated to cow, control and kill using the multiple security organisations that enabled a country to devour itself. Under the American occupation of 2003 it became the even more intensely fortified Green Zone, a surreal dystopia of six square miles in which Iraqis were largely unwelcome in their own capital.

Today, after a 12-year interlude, the Green Zone is open to Baghdadis again. But as so often in their extraordinarily bloody history, Iraqis find they have very little to cheer about as the country tears itself apart. The great city of Baghdad survives, but its people are once again engulfed in terrible violence.

Justin Marozzi