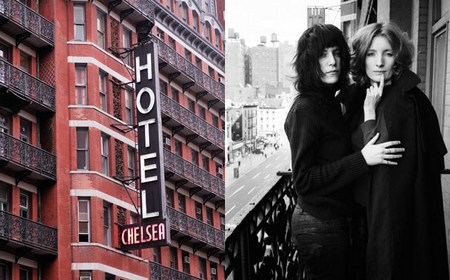

Tales from the legendary hotel-slash-commune that housed Jackson Pollock, Dylan Thomas, Arthur Miller, Bob Dylan, Robert Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith, and Sid Vicious—told by residents like Rufus Wainwright, Betsey Johnson, R. Crumb, and Andy Warhol.

Wll vanish before the city’s merchant greed, Wreckers will wreck it, and in its stead

More lofty walls will swell

This old street’s populace. Then who will know

About its ancient grandeur, marble stairs,

Its paintings, onyx-mantels, courts, the heirs

Of a time now long ago? . . .

—“The Hotel Chelsea” (1936), Edgar Lee Masters

Today the halls of the Chelsea Hotel are salted with dust. The hundreds of paintings that adorned its walls have been locked away in storage. The doors to abandoned apartments are whitewashed and padlocked. Hotel operations ceased in 2011 for the first time in 106 years, and now the few remaining residents roam the echoing corridors like ghosts. They have watched workers haul out antique moldings, stained glass, even entire walls. Ancient pipes ruptured during renovations, flooding apartments, and neighbors returned home from work to find their front doors sealed in plastic wrap. The Chelsea’s new owners say that the building had fallen into dangerous disrepair, and they are restoring it to its original condition. Some residents believe that they are being forced out, and that the Chelsea as they know it—and as it was known to residents from Sherwood Anderson and Thomas Wolfe to Sid Vicious and Jasper Johns—will soon vanish before the city’s merchant greed.

Dystopias always begin as utopias, and the Chelsea is no different. Though in its current state it bears an unfortunate resemblance to Los Angeles’s Bradbury Building as transfigured in Blade Runner, the Chelsea was originally conceived as a socialist utopian commune. Its architect, Philip Hubert, was raised in a family devoted to the theories of the French philosopher Charles Fourier, who proposed the construction of self-contained settlements that would meet every possible professional and personal need of its inhabitants. After the stock-market crash of 1873, Hubert decided New York was ready for its own Fourierian experiment and devised a plan to build cooperative apartment houses in New York City. Tenants would save money by sharing fuel and services. Hubert’s creations—New York City’s first co-ops—were tremendously successful, and none more so than the Chelsea, which opened in 1884. Keeping with Fourier’s philosophy, Hubert reserved apartments for the people who built the building: its electricians, construction workers, interior designers, and plumbers. Hubert surrounded these laborers with writers, musicians, and actors. The top floor was given over to 15 artist studios. Hudson River School paintings hung in the common dining rooms, and the hallways and ceilings were decorated with natural motifs. At 12 stories, the Chelsea was the tallest building in New York. (For a full history of the Chelsea Hotel and its origins, see Sherill Tippins’ forthcoming Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York’s Legendary Chelsea Hotel.)

But Hubert’s grand experiment went bankrupt in 1905, and the Chelsea was converted to a luxury hotel, which was visited regularly by guests such as Mark Twain, William Dean Howells, and the painter John Sloan. After World War II, as the hotel declined and room prices fell, it attracted Jackson Pollock, James T. Farrell, Virgil Thomson, Larry Rivers, Kenneth Tynan, James Schuyler, and Dylan Thomas, whose death in 1953 further enhanced the hotel’s legend. (“I’ve had 18 straight whiskies,” said Thomas, after polishing off a bottle of Old Grandad on the last day of his life. “I think that’s the record.”) Arthur Miller moved into #614 after his divorce from Marilyn Monroe. Bob Dylan wrote “Sara” in #211; Janis Joplin fellated Leonard Cohen in #424, an act immortalized in “Chelsea Hotel #2” (“you were talking so brave and so sweet/giving me head on the unmade bed”); Sid Vicious stabbed Nancy Spungen to death in #100. Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey at the Chelsea, William Burroughs wrote The Third Mind,and Jack Kerouac had a one-night stand with Gore Vidal. In 1966 Andy Warhol shot parts of Chelsea Girlsat the hotel. In 1992, Madonna, a former resident, returned to shoot photographs for her Sex book. Christo and Jeanne-Claude once stole the doorknob from their bathroom door for an art project; the doorknob is now in the permanent collection of the Hirshhorn Museum.

In its last half-century, the Chelsea was run as an informal artists’ colony. Artists traded paintings for rent, or lived for free, subsidized by the exorbitant rates paid by the troubled children of the hyper-rich—another demographic that has historically been drawn to the hotel. Tourists from all over the world paid for cheerless rooms and the opportunity to sit in the moldering lobby and gawk. The curator of this living museum, the gatekeeper responsible for deciding who should be allowed admittance and for how much, was Stanley Bard. His father, David, had been one of three partners who bought the declining hotel in 1943; Stanley assumed management in the early 1970s. An institution himself, he’s been called everything from “the best loved landlord in history” to “the biggest starfucker of all time.” But six years ago, he was forced out by the heirs of the other two ownership families, who wanted to sell the hotel against his wishes, and two years ago the Chelsea sold to the real-estate magnate Joseph Chetrit for approximately $80 million. Chetrit, who refused to talk to the press, has recently sold the property to King & Grove, a boutique-hotel chain, which is currently overseeing a $40 million renovation.

So far, the promised “re-invention” of the Chelsea has not gone well. Some of the building’s remaining tenants, alleging that Chetrit had tried to bully them into vacating their apartments, filed a lawsuit alleging hazardous living conditions and intimidation. The tenants’ efforts drew the support of former residents, architectural historians, and local politicians. That suit settled two weeks ago, but the building still resembles a construction site, and tenants who did not receive a settlement complain that little has changed. I set out to chronicle its history in the words of those who have lived, worked, caroused, and died there. This is the story of the Chelsea Hotel as told by its past and future ghosts.

NICOLA L.(Artist, current resident): The first time I came to the Chelsea, I was invited to New York to perform at La MaMa in 1968. I remember the first floor was only prostitutes and pimps. One pimp had pink shoes. For me it was unbelievable. It made Paris look like the provinces by comparison. But prostitutes and pimps were a part of the package of the Chelsea. And artists—I will not say that they are prostitutes, but they are selling themselves.

SCOTT GRIFFIN(Theater producer and developer, former resident): You had a constantly changing cast of residents, some of whom had been there for a hundred years, some who were only there for a month. There was an incredible cross-pollination of people of all ages, social classes, and levels of accomplishment. And it was all curated by Stanley Bard. It was a vibrant, dynamic place to be, particularly as a young person. You could go to one floor and talk about the theater with Stefan Brecht and go to another floor and talk to Arnold Weinstein about poetry and then have dinner downstairs with Arthur Miller. There aren’t many buildings in New York like that.

GERALD BUSBY (Composer, current resident): Stanley Bard had a sense of who was really an artist. He also had a sense for rich dilettantes. He himself was a dilettante who wanted to be part of the artistic scene and wanted to be identified with it. So he became the landlord daddy for artists. It was an astonishing role that he created for himself. His relationship with every tenant was personal. That was the way he behaved—he took everything personally.

MILOS FORMAN (Film director): I finished a movie in 1967, and I didn’t have any money. Somebody told me that Stanley Bard would let me stay at the Chelsea until I would be able to pay him back. At the time all I knew about the Chelsea was that some people in the hippie world were staying there. But I didn’t know that it had the slowest elevator in the whole country.

NICOLA L.: Anything could happen in the elevator. It was either Janis Joplin or the big woman from the Mamas and the Papas who tried to kiss me in the elevator. I can’t remember which. It was a crazy time.

MILOS FORMAN: Once I was going up in the elevator to my room on the eighth floor. On the fifth floor the door opened, and a totally naked girl, in a panic, ran into the elevator. I was so taken aback that I just stared at her. Finally I asked what room she was in. But then the elevator stopped and she ran away. I never saw her again.

And I remember in the floor above me there was a man who had in his room a small alligator, two monkeys, and a snake.

GERALD BUSBY: There were rooms kept aside for black-sheep children from rich families, who paid Stanley to babysit. The most auspicious of these was Isabella Stewart Gardner’s grandniece, who had the same name: Isabella Stewart Gardner. She was an excellent poet—a poet laureate of New York in the 70s—and married to Allen Tate. She was also mad as a hatter, a total masochist, alcoholic. She’d get drunk and meet someone and he’d take her up to her apartment and fuck her and beat her up and steal something, and then she was totally happy.

BOB NEUWIRTH(singer, songwriter, producer, artist): That was the period in which the Chelsea Hotel began to take on a tabloid character. It moved from the realm of a bohemian hotel to a kind of hot spot. Rock-and-roll people began to stay there. Andy Warhol and the people who hung out in the back room of Max’s Kansas City were discovering the place.

GERARD MALANGA (Poet and photographer): When Andy and I traveled, it was pretty much first-class, but then we weren’t actually “living” in those hotels. The Chelsea was different. It appeared a bit rough at the edges. Quite seedy. Paint peeling. Throw rugs needing a cleaning. I don’t recall if the maid ever turned up the sheets. But nothing I couldn’t live with.

Chelsea Girls was one of those divine accidents. When we first started filming, we had no title or concept in mind. We were shooting wildly, you might say. Somehow we found ourselves continually going back to the Chelsea to film. It was our instant set. Andy liked the idea of shooting “on location.” So that’s how the title for the movie pretty much evolved. Not all the sequences were shot there, but structurally when we pieced the sequences together, it gave the appearance that they were shot in different rooms.

BETSEY JOHNSON(Designer): I left a husband [John Cale] in 1969 and went to the Chelsea with a toothbrush. I meant to stay for a couple of days, and I stayed eight months.

I had a huge loft, and I was making costumes for the movie Ciao! Manhattan. I would dress up in them and sit in the lobby to see if they got any reaction. I sat there with cone ears, cone tits, cone knees, in a stretch black knit. I looked a little strange, but I can’t remember any laughing or harassment. It was no big deal.

MILOS FORMAN: One night, around two in the morning, a fire alarm went off. It was a few days after a horrible fire in Japan, and we’d seen on television people jumping to their death from a burning building. So I panicked. I ran into the corridor to see what was happening.

There were other doors opening and people asking questions, and suddenly I heard a bang: I had a window open and the draft closed my door. My key was inside, and I was naked in the corridor, which was beginning to fill with people.

Across the corridor there was a lady. I said, “Do you have any pants?” She said, “No, I don’t.”

I tried to call downstairs, but they just yelled back at me: “The building’s on fire, and you want us to bring you a spare key!” So this lady said, “Well, I can lend you a skirt.”

I put on the skirt. By this point I can see down the long spiral stairwell that everybody is going to the rails to see what’s happening. I was on the eighth floor, and we could see, on the fifth floor, that firemen had started to blast an incredibly powerful water cannon through the door of an apartment to extinguish the fire. From above we saw water running down the stairwell through the different floors, like a cascade. It was like a Niagara Falls.

Then we saw the firemen carrying out an old lady. We didn’t know if she was dead or not—to this day I don’t know if she was dead—but they had blasted her apartment with so much water that she might have drowned.

It seems cynical, but when they were pouring the water in, all of us on the floors above were just standing and watching, as on a balcony in a theater. A bottle of wine was passed around, and some joints, and everyone drank, smoke, talked, and watched the waterfall.

But when they brought out the body everything stopped. There was total silence except for the sound of the water running down the stairs. We all waited for the elevator—the slowest elevator in the world—to come up to the fifth floor. Finally it came, and the fireman took away the lady. And then, the moment the elevator door closed, bang: bottles of wine, joints, everybody talking, and the show went on.

JUDITH CHILDS (Current resident): Edie Sedgwick set her mattress on fire. She was staying across the hallway from our apartment. We had a very alert fellow at the desk that night, and he hadn’t liked the way she looked when she came in, so he went to check on her and found the fire. Later, after the firemen came, we were all in the lobby, mostly in our nightclothes. When the firemen said everything was O.K., we all went into the El Quijote [the Spanish restaurant on the hotel’s ground floor] and had a drink—in our nightclothes. Now that was very fine. That was the moment when we got to know a lot of the people in the hotel.

BETSEY JOHNSON: In those days, nobody was famous. Nobody was like whoa, except for Andy and Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger. Everyone else was on the same plane of having an idea, believing in it, and going for it. Needing to talk about it, needing support from other people in the same boat. It was a clique, but it was based on talent and passion rather than who you knew or how much money you had. It felt real homey and droll and addictive. I made handmade clothes for Nico. I was working with the Paraphernalia clothing boutique, and my fitting model was Edie Sedgwick, who also was staying at the Chelsea. That’s when, somehow or other, her room caught on fire. She was wearing my dress!

It was very comfortable because there was no scrutiny; there was no “you’re too weird for us.” Do you remember that Buñuel movie, where the dinner guests can’t leave the party—The Exterminating Angel? That’s what the Chelsea was like.

WILLIAM IVEY LONG (Costume designer): I moved to the Chelsea because I knew that Charles James lived there—the great Charles James, the Anglo-American couturier, designer, friend of Cecil Beaton’s, friend of everybody. He lived there in great squalor and never accepted assistants or interns.

Mr. James had two rooms in the Chelsea Hotel. There was peeling paint, maquettes of dresses hanging from the ceiling. He dyed his hair with shoe polish because it would drip like in Death in Venice. It probably wasn’t shoe polish, but I called it that. He had a dog, Sputnik, who had an infection and wanted to scratch his ear. So he wore one of those big Elizabethan collars.

I would do things like get him food or cook, and he would eat dinner at my apartment. I’d walk the dog. He already had an assistant, so I was just a gofer. I worked with him until he died, in ’78. I’ve known about five world-class geniuses. One of the traits of genii is they dare the world to understand them. Many of them are belligerent and stubborn and unpleasant. This is justified because the aura that they give off is so appealing, so compelling, that you’re drawn to them. It’s a little test because they’re aware of their special gifts. Charles James’s particular test was that he was an asshole to everybody.

BETSEY JOHNSON: Charles James! We used to send notes to each other. He was a private guy—I never saw him. I would invite him to the shows, and he’d write a note about how he loved my work but he wasn’t feeling well so he couldn’t come. It was an old-fashioned thing—you’d leave a note in his hotel mailbox. I wish I’d had the money to have him make me a gown.

RENE RICARD (Painter, poet, critic, current resident): Charles James was a dear friend of mine when I was a little boy—17, 18. He was mad as a hatter. I had no idea how famous he was. We used to go to Max’s together. One night Charles was at a booth with me in the back room and someone sent over a bottle of champagne with a glass. I don’t know who the person was, but Charles started shaking. He turned the glass over on the bottle and told the waiter to take it back. Everybody was trying to help Charles, and you couldn’t help Charles.

He spoke with a beautiful Mayfair accent, very much like Joan Greenwood in The Importance of Being Earnest. Which was rather interesting considering that he came from the Midwest.

GERALD BUSBY: I arrived here in 1977. Virgil Thomson was my mentor, and he called up Stanley Bard—the famous, outrageous, phenomenal creature that he was—and said, “Stanley, this is the kind of person you’re supposed to have here.” So that was that.

The Chelsea then was bizarre and wonderful and strange. It was just coming out of its super drug haze. I remember there was a guy who sold grass. He had a five-foot-high pile of grass in the middle of his living room with roaches running out. It has always been a place where, because of Stanley, you could do virtually anything short of murder, though that took place too. There used to be a murder, a suicide, and a fire every year. You’d go into the elevators, and you’d see a shoe and a sock. Somebody had committed suicide by jumping down the stairwell and, on the way down, lost a shoe.

My boyfriend and I lived across from an apartment that always had young married couples who fought bitterly, screaming and slamming doors. I came out one day and a man from one of the most vociferous couples was leaning against the wall, drinking a can of beer. He looked flushed and weird. He said, Hi. I said, Hello. I approached the elevators, and 20 policemen came rushing up and grabbed him. The man had just shot and killed his wife, you see, and he had been waiting for the police to come.

If you paid your rent and didn’t cause too much trouble with the manager, you could get away with almost anything. Many people became drug addicts here—including me for a period, when my partner died of AIDS—because you can do anything. The atmosphere encouraged outrageous adventures. That was because of Stanley.

JUDITH CHILDS: My husband, Bernard Childs, died here. The ambulance came. On that late afternoon, after I got back from the hospital, all of the neighbors visited, even those who didn’t know us, who weren’t personal friends.

Something else happened that I always will be grateful for. The housekeeper—at that time we still had maid service—came in and took away all of my husband’s underclothing. She changed the sheets and I never saw the underclothes again. That was a beautiful, incredible thing.

GERALD BUSBY: It was a perfect place for me mainly because of Virgil. He lived there like a graduate student. He had a wonderful, six-room apartment, in its original condition from 1884, but it had been part of an 11-room apartment. He got the part that didn’t have a kitchen. So he built a makeshift kitchen in the linen closet.

I met Virgil when I was working as a cook. After I had an experience cooking for him, I said, “Oh, Virgil? I’ve written a few pieces and I wondered if I could show them to you.” He said: “Not until I taste more of your food. I need to see if you can put things together and turn them into something else.”

He’d call when he held fancy dinners at his apartment—when he would entertain Philip Johnson and his sister, for instance. He would say, “Can you run up a crème brûlée?” And I’d run him up a crème brûlée. So our relationship was mainly about food.

GRETCHEN CARLSON (Current resident): My husband, Philip Taaffe, was living in Naples in 1989, and he wanted to move back to New York. A friend was living here, and she told us that Virgil Thomson’s apartment was going to be up for sale. He had just died. The idea was to leave the apartment in its original state. It’s one of the few apartments that wasn’t chopped up into little pieces when the hotel became a flophouse in the Depression. Virgil is present in this place. Like a benign, gentle ghost. He died right here.

WILLIAM IVEY LONG: I had this fabulous apartment in the front: #411. It proved to be very exciting, because it’s also the number that people dial for information. I was always answering people’s questions in some strange way. Sometimes, though, I would actually give them the number they wanted. I would look it up for them.

My next-door neighbor was Neon Leon. He had a white girlfriend and a black girlfriend and, I think, children with each. They would take turns fighting with him and setting fire to the mattress. I would take gaffer’s tape and tape around my door because the smoke would be coming in, but I would be too busy to evacuate. There would be foghorns and people yelling, “Everyone out!”

VIVA (Writer, painter, actor, dilettante): There were a lot of suicides out those windows. One night, a guy from a floor above us landed on a metal table in the courtyard—on his head.

The very next day another guy jumped out the window onto the synagogue next door. It was just after John Lennon was shot. But this man didn’t die—he was bloody but conscious. He was being carried down the hall on a stretcher. I asked him, “Why did you jump out the window?” He said, “Because John Lennon was shot.”

GERALD BUSBY: I was cooking dinner one night for Sam, and I noticed that the flame on the stove was turning a very strange color. The atmosphere was palpably different. You couldn’t quite define it. What was happening was that there was a fire on a lower floor and enormous billows of smoke were coming up the stairwell. When we opened the door, a black cloud of smoke came in. We ran to the windows to breathe. There were people outside shouting at us, “Jump!”

It turned out that a country-Western singer had a fight with his girlfriend. She poured kerosene all over his fancy shirts and set them on fire. He was asphyxiated, and the whole hotel was filled with smoke.

We went out on the fire escape and were rescued by cherry pickers from fire trucks.

ED HAMILTON (Writer, author ofLegends of the Chelsea Hotel: Living with Artists and Outlaws of New York’s Rebel Mecca,current resident): I loved it immediately because it was my ideal of bohemian heaven. People left their doors open; they’d invite you in for a glass of wine. It had a vital energy. At the same time, it was a little bit scary because, in addition to the artists and writers, there were all these crazy characters, schizophrenics and junkies and prostitutes. Mine is an S.R.O. room, so it’s got no kitchen, and the bathroom, which is shared between four rooms, is next door. Junkies would break the lock and go in and shoot up all the time. That was the biggest problem. They’d stay there for hours because they would nod off on the toilet, and they’d leave needles and blood on the floor.

And the prostitutes—it doesn’t sound so bad that there would be prostitutes. But the way it works is that three or four of them rent a room and they take turns with their johns, a john every half an hour, so there’s a steady stream of people that you don’t know. When one of the prostitutes is working, the others have to hang out somewhere, so they usually go to the bathroom. They’ll stay in there for hours. I’ll ask them, “Why are you always in the bathroom?” And they’ll say, “I’m using the toilet. What’s your problem? If you need to use the bathroom, just knock.” But you get sick of knocking on the bathroom all the time to get rid of the prostitutes.

They also have a habit of hanging their underwear in the bathroom. There’s underwear hanging all over the mirror and the sinks and the tub and the shower rod. They have a lot of underwear, prostitutes do. That’s something I’ve noticed.

GERALD BUSBY: There were no leases. Stanley would let you get behind in your rent. If you were really an artist, you could get behind for a month or two or three. But he had this wonderfully bizarre sense of timing: you’d be alone in the elevator and just as the door was closing, he would dash in and you were stuck. Or he would yell after you in the lobby, to embarrass you. Viva used to have these loud, screaming arguments with him in the lobby. Stanley loved that. He liked confrontation. She would say, “You fucking asshole! I don’t know why you think I’m supposed to pay you any more rent!”

NICOLA L.: One day Viva decided that her apartment was too small. The room next door was empty, so she broke through—she made a big hole in the wall. There was a big duel with Stanley about that. She always chose the best moment to fight with him, like noon, when all the tourists were checking out.

ANDY WARHOL (diary entry, October 12, 1978): The police just arrested Sid Vicious for stabbing his 20-year-old manager-girlfriend to death in the Chelsea Hotel, and then I saw on the news that Mr. Bard was saying, “Oh yeah. They drank a lot and they would come in late. . . . ” They just let anybody in over there, that hotel is dangerous, it seems like somebody’s killed there once a week.

RENE RICARD: Sid Vicious was the sweetest, saddest boy. He didn’t know what happened to him. It was so sad. He was so sad.

WILLIAM IVEY LONG: I remember walking past a body. It was not the first body I had seen—when you live in an old S.R.O., which part of the Chelsea was, old people die. But they usually don’t sit in the lobby. A policeman was guarding it. When I asked about it, they said, “That’s that rock-and-roller’s girlfriend.”

Everybody said, “Oh, Sid Vicious killed her, slashed her throat.” But I didn’t see any blood. The body was on a gurney, covered by a sheet. A low gurney, I remember, knee-high. Not one of the ones they use for living people.

RENE RICARD: Stanley denied everything. “Killed his girlfriend in my hotel? Nobody ever killed his girlfriend in my hotel.” “Fire? Edie never had a fire.” He’s totally rewritten the history. I think that’s how he lives with himself.

EDDIE IZZARD (Actor and comedian): The first gig I ever did in America was in Memphis, around 1987. It was a street-performing gig, and a British woman there said, “If you’re ever going to go to New York, stay at the Chelsea Hotel. It’s crazy. You gotta go there.”

So I thought, “O.K., I’ll go there.” I hadn’t heard of it before.

The rooms were bonkers. The rooms were so bonkers. You’d go down a hall, which used to lead to a door, but they closed the door off, so it was just this bit of corridor that was useless. Every room had its own theme, but the themes were usually just whatever they’ve managed to get into that room. I remember staying there when I was performing Dress to Kill at the WestBeth Theater. I was walking around with makeup, dressed in heels, and I think I just blended right in. It was just odd, fucking odd, but I liked it.

LINDA TROELLER (Photographer, current resident): I moved in around 1993. I’d broken up with my French boyfriend, and my collector, who always stayed at the Chelsea Hotel, said, “Why don’t you see Stanley Bard?” I did, and he said that he happened to have something, but only if I moved in by two o’clock the next day.

It was room #832. He told me it was a writer’s room, that it had a big history. He showed me the bedroom and the bathroom, which was beautiful. Then he opened the closet and there was a huge black snake. It was rattling in a cage. Stanley closed the closet door. He said, “Don’t mind that. There were Goths staying here, but we’re getting them out!” He was a great salesman.

RENE RICARD: After September 11th, I was homeless. I was walking down 23rd Street, and just by coincidence I had $3,000 on me. Stanley Bard is standing outside the hotel. He says, “Rene, why don’t you move in?” Every time he saw me he’d ask me to move in. He’d come on with a big smile—you know, the host extraordinaire. But this time I said, “Sure, absolutely. Show me a room.”

He showed me the smallest, worst room they had. I ask how much it was, and it’s as if he could read what was in my pocket: “$1,500 a month,” he said. He says he needed one month’s rent and one month in advance. That’s $3,000. I just emptied my pocket and gave him the money. If you could see the old payment system, what the documentation looks like when you pay your checks—it’s incomprehensible. It’s state-of-the-art somewhere. Perhaps Romania.

RUFUS WAINWRIGHT (Musician): I was at the Chelsea for about a year, writing my second album,Poses. I was gathering material and anecdotes and songs and boyfriends. I used to party a lot with Alexander McQueen there, and I fell in with Zaldy Goco, Susanne Bartsch, Walt Paper, Chloë Sevigny—that set. The nightclubbing, Limelight, club-kid culture. Those who had survived the 90s.

I felt that for the album I was writing, there was no better address to have in terms of communicating decadent, sad 20s esprit. I mean, you can’t talk about the Chelsea and not talk about drugs. I don’t do drugs these days, so it’s fine, but it was my last grasp at extreme youth, with all the trimmings: not just the drugs, but the alcohol, the sex, everything. I was approaching my Saturn return and things were starting to get a little darker and a little more sinister. There’s nothing like those high ceilings at the Chelsea Hotel to accentuate that—the phantoms up near the trellises. I couldn’t have asked for a better place.

ARTIE NASH (Author, activist, gadfly, current resident): Rene Ricard was the first person I met after I moved in. I woke up to someone singing opera in the shared bathroom. It might as well have been right outside my door. It was four a.m. He told me that a 15-year-old hooker had lived in my apartment before me, which was both sad and fun at the same time. He loved my room, he said. He assured me that only the best people had committed suicide there.

GRETCHEN CARLSON: That’s what they called the little rooms: suicide rooms. This was a place that drew people who’d hit bottom. For some reason, they had it in their mind that they should come here.

ED HAMILTON: Dee Dee Ramone was about the craziest person I’ve met at the Chelsea. He was staying next door from me, and I didn’t know it was him. There were construction workers upstairs, and he started banging on my wall, “Shut up, shut up!” Then he came to my door, dressed in just his jockey shorts and covered in tattoos. He said, “Shut up with that racket!” I said, “It’s not me, Dee Dee. It’s those guys upstairs.” He ran back into his room and threw open his window and started yelling at them, “You shut up, up there! Motherfuckers! I’ll come up there and kill you!”

Of course they deliberately made more noise, and that just drove him nuts.

R. CRUMB (Artist): A bunch of really crazy people hung around the Chelsea. You could tell that people were going there just because of its reputation—poseurs with artistic pretentions or European eccentrics with money. There’d be poseurs sitting around the lobby. The lobby was really annoying.

I only started staying there about 10 years ago. It was always when somebody else paid for it. I never could afford to stay there—even 10 years ago, it was too expensive. Except for the old residents who clung desperately to their rooms and by some law were not allowed to be kicked out, the guests there were all arty-farty pretentious people with money who wanted to stay there because Sid and Nancy lived there. That was my impression, anyway. The whole thing seemed extremely self-conscious to me.

LOLA SCHNABEL (Artist, former resident): My father had always rented a room in the Chelsea. Guests would stay there, and collectors. He always dreamed of living in the Chelsea, but he was in a different part of his life, he had a family, so it just sat there. When I was 22, I got a scholarship to Cooper Union. My father figured I was on a good track and could come up with the rent, so I moved into the Chelsea. I would do my homework at the bar of El Quijote. I would always order a croquette, until one day, when I found a human tooth in my croquette. Then I stopped eating food there. But I still sat at the bar—it’s a great place to do homework.

ED HAMILTON: As the 90s moved into the aughts, Stanley started renovating the place. It needed it. It was run-down. They had fluorescent lights in the hallway, checkerboard linoleum.

He replaced the lighting and the linoleum. There was a lot of pressure on him from the board to make more money. Some of the marginal characters got edged out, especially the junkies and the prostitutes who didn’t pay their rent. The people in the tiny rooms got squeezed out, and the rooms were combined for people who could pay more. It was the same story all over New York.

JUDITH CHILDS: Some people say it was all over long before Stanley Bard left in 2007, but it wasn’t.

When the Chetrits came in and fired everyone who worked here, the whole staff, we went through a mourning period. They were part of our family. The day that happened, everybody was hugging and crying in the lobby. It was shocking. Then they closed the hotel. And finally they took down all the paintings. We were unbelievably sad. It was like the Panzer Division moving into Poland. And they know that we feel that way.

LOLA SCHNABEL: It’s sad to see the bare walls and to walk in the lobby and see an unfamiliar guy at the desk who doesn’t even say hello. The staff used to look out for you. If you were breaking up with your boyfriend, they’d give you a pat on the back and say, “It’s only a setback.” They would help you if you were carrying too much stuff—they don’t do that now. The doormen used to always give me comments about my outfits. I have this one pair of boots that I can’t take off by myself, and it was nice when the old management was there, because I had someone to help me take off my shoes.

ED HAMILTON: They took down all the art and put it into storage.

ED SCHEETZ (Founder, King & Grove [new owner of the Chelsea]): The art has not disappeared. It’s all stored, catalogued, and being taken care of so it doesn’t get damaged during the renovation. It’s not sold, it’s not gone, nothing.

As a hotel person, I’m involved with a lot of hotels, including iconic ones like the Delano in Miami. The Chelsea is a dream deal for someone in my career. It’s a fantastic investment, but it’s also just a lot of fun to help shape its future and its renaissance. Some people say, “Don’t change anything. You’re ruining the Chelsea!” That’s Luddite. It’s ridiculous. Are we destroying the spirit of the Chelsea? No. It was not destroyed, but it was trampled on for many decades, and we’re trying to bring it back. I think we will successfully do that.

We’re going to have $130 million or something invested in this building, plus all this time and energy. People act like it’s in our interest somehow to destroy it. Even if you say, like everybody does, that we’re just greedy developers, well, the best way for us to make money, and create something that is long lasting, is to do the right thing. That’s what is going to attract guests, people to the restaurants, visitors, tenants. That’s what’s going to make the most money. There is no incentive for us to do a bad job or make it into shiny glass condos. Staying true to the spirit of the Chelsea is not just the right thing—it’s the most profitable thing.

SCOTT GRIFFIN: The thing that is very hard to grasp about the Chelsea is that it’s all about the mix. It doesn’t matter whether people are paying a lot or a little, it’s about the mix, and the minute the Bards walked out that door, that mix was gone. Without that mix, the building just doesn’t work. If the new owners can quickly grasp the importance of the building’s history, if they can think outside of the box, as all smart people do, and learn to embrace the many eccentricities and unusual opportunities that this building presents—if so, they could be great landlords.

But in the last two years, the building has continued to deteriorate. I moved out in April—I feel it’s dangerous to be there now. The workers are routinely causing flooding, shutting off power. They’re destroying the building.

ED SCHEETZ: I understand that the renovations are disruptive and aggravating. But it’s a short-term inconvenience for a long-term permanent improvement. The building is a mess right now. It’s amazing they even allow people to live there. It is not complying with fire codes. It’s not complying with electrical codes. It does not comply with anything. It’s not safe; it’s not modern; it doesn’t have air conditioning; it doesn’t have working, functioning plumbing and heating. When you put in plumbing and air conditioning and modern electrical systems and comply with fire codes, yeah, that’s a pain. But it needs to be done, and it’s for the benefit of everybody, including the current residents. And we’ve done everything that anybody has asked us to do to minimize the intrusion. If they say, “Hey, a pipe broke and it leaked. Can you clean my apartment?” We say, “Sure.”

R. CRUMB: At a certain point you just give up on Manhattan. What can you do to stop it? Nothing, unless the whole fucking economy collapses. Manhattan is going to keep pushing in that direction, more and more expensive condos, apartments, hotel rooms. Then again, it’s always the end of some era in New York. They’ve been saying that about New York since before the Civil War.

MILOS FORMAN: These things are unstoppable. And it’s a pity. Greed is overwhelming.

GERARD MALANGA: Whenever friends planning a trip to New York would ask me about the Chelsea, I’d recommend they reserve a room at the Gramercy Park. In fact, until 15 years ago, the Chelsea rates were higher than those of the Gramercy Park. I have no sentimental attachment, none whatsoever to the Chelsea. I think the best thing that can be done with it—and I say this with the hope that its architectural integrity be preserved—is that some hotelier take it over and transform it into the luxury hotel it’s begging to be.

WILLIAM IVEY LONG:I’m very sentimental about it. Stanley Bard and the Chelsea Hotel saved my life. He certainly saved my artistic life. Stanley accepted the Bohemian biorhythm. This biorhythm is endangered. Stanley was determined that he wasn’t going to be the one to put the lid on anyone’s career. The people who could pay, did pay. The rich Italian tourists paid. The even richer rock-and-roll people paid. The people who couldn’t, he supported them. I had some depressive moments there. But Stanley was one of the few people in New York saying, “You can do it.” His belief in talented people will be his legacy.

ARTIE NASH: I’ve lived here since late 2005. I’m the last resident to get a lease under Stanley Bard. I live in Dylan Thomas’s old apartment. For a year or two, when Stanley was still here, it was as nurturing an existence as you could hope for. I’ve heard it described as a vortex. People do their best work here. But the spirit of the place, what inspired people to live here, has been drained.

MICHELE ZALOPANY (Painter, current resident): It’s a tomb now. There’s no life anymore. The human energy has changed completely. I feel like I’m in the Twilight Zone.

ED HAMILTON: It’s hard to say where I’d end up if I had to leave the Chelsea. This place is synonymous with my experience in New York. Certainly I wouldn’t be able to find another place for $1,100. Not in Manhattan—probably not in Brooklyn, either. And I’d never find a place like this where everybody’s an artist. There are no places like that. Yeah, it’s a shame. This is the last outpost of bohemianism in New York.