Art thou not thyself the wind with shrill whistling, which

bursteth open the gates of the fortress of Death?

Art thou not thyself the coffin full of many-hued malices and

angel-caricatures of lifе?

Friedrich Nietzsche: Thus Spаke Zarathustra

In an almost forgotten essay “Wotan”, Karl Gustav Jung harks back to the experience of a “fifteen-year-old Nietzsche at school in Pforta […] It is thus depicted in Autobiographischen Aufzeichnungen(Autobiographical Notes) compiled by his sister Elisabeth Foerster Nietzsche”:

“There Nietzsche describes a fantastical night walk through the dark forest, when he is suddenly startled by ‘a piercing cry from a nearby madhouse’, thereafter meeting a hunter with ‘wild, unpleasant features.’ In a valley ‘surrounded by dense undergrowth’, the hunter takes a whistle in his mouth as a thunderous bang sounds, causing Nietzsche to lose consciousness and later awaken once more in Pforta.”

“It was a nightmare.”

His poem “Ariadne’s Lament” is no less explicit:

Adriadne’s Lament

Prone, shuddering

Like one half dead, whose feet are warmed;

Shaken, alas! by unknown fevers,

Trembling at pointed arrows of glacial frost,

Hunted by you, Thought!

Nameless! Cloaked! Horrid!

You hunter behind clouds!

Struck down by your lightning,

Your scornful eye, glaring at me out of the dark!

Thus I lie,

Writhing, twisted, tormented

By all the eternal afflictions,

Struck

By you, cruelest hunter,

You unknown god…

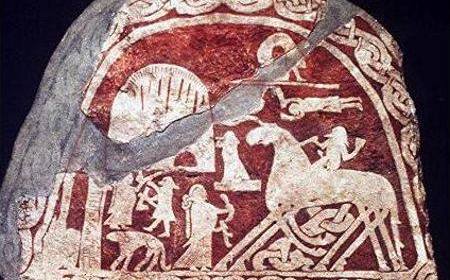

The unknown god and “cruellest hunter of them all” is no doubt Odin, or Wotan, the Germanic or Norse god of poetic inspiration and warrior frenzy. That night’s appearance (in Nietzsche’s dream) in the forest of the unknown storm god, a whistle piercing the air, can hardly be misunderstood. Today, as in the past, the depiction of Christ on a horse can still be found in backwater inns and taverns, although patrons remain often unaware that their gaze falls not on Jesus Christ, but on Odin himself:

“In a sect of simple people based in Northern Germany, he appears on the wall of a meeting room, hesitantly portrayed as the figure of Christ riding a white horse.

In the early 1930s, a youth movement captured thousands of young men and women who, “armed with rucksack and lute”, wandered from Nordkapp to Sicily. Towards the end of the Weimar Republic, the movement was enlarged by a multitude of unemployed workers – a surprising turn of events in Germany (though not perhaps in Russia), given our widespread prejudice towards the nation as an essentially philistine, mercantile and petty bourgeois society. This proved to be the restlessness that would quickly capture millions more, as “Wotan, the traveller, is awakened.”

His awakening, or his rebirth, as Jung notes, was immediately “celebrated with several bloody sheep sacrifices,” to transform the wandering of countless people into a million strong march.

***

Wotan-Odin, the tireless traveller, mysterious guest and initiator of unrest, was banished by Christianity – but never completely – initially being transformed into the devil. Thereafter, as Jung notes in his famous essay, Odin was “flickering away in stormy nights like a deceptive light, like an apparition of a hunter in a chase with his hunting party” He would be spotted by travellers close to a village or by those lost deep in the forest, just as young Nietzsche had. However, where is the chase headed, what is the unknown god searching for? This is the scene of Odin’s wild hunt, together with einherjars and valkyries, to be found in German lands all through the middle ages. He appears suddenly, primarily at night, galloping away, akin to a storm. No doubt, he will return one day. As already denoted, he may, quite unexpectedly, appear as a figure of Christ, yet also as the god of war and harbinger of catastrophe.

The figure of Wotan is reminiscent of the Serbian Saint Sava1, although the former was transformed into the persona of the devil, while the latter was elevated to sainthood to a staunch supporter of the Christian faith.

Saint Sava was likewise followed by wolves: “In Serbian folklore, Saint Sava is always followed by wolves, his hounds, as in Germanic mythology, where wolves are the hounds of Wotan” (Veselin Cajkanovic: Serbian Myth and Religion). In both cases, wolves are the souls of the dead, the spirits of the ancestors.

Drawing further similarities to Odin, he is also a tireless traveller, journeying from place to place in a ceaseless search for something. He is the mysterious guest with knowledge of “occult secrets”, who will in later times be associated with the invention of literacy, just as the discovery of runes was attributed to Odin-Wotan. As noted by Veselin Cajkanovic, the anger that often overcomes him is another parallel: “The natural conclusion in this case would be to think of the ancient Indoeuropean gods – of Indra, Wotan, Donar – whose prerogative these ‘terrible passions’ are, to use the term of Plato, whose power and lordliness manifests itself in this very anger.”(Veselin Cajkanovic: Serbian Myth and Religion).

***

Sometimes we awaken before daybreak, invigorated by a dream or awoken by an inexplicable desire: to leave behind the usual way of life, to set out off the beaten track, maybe on a path once seen in the forest or on one which we behold every morning from our apartment window. In any case, we find ourselves here more or less by chance; we could reside just as well in a different place. The need to head off into the unknown, away from the daily routine, is a need felt by every human being – it will be with us throughout our lives. This urge is depicted by Arthur Rimbaud in one of his early poems called “Sensation”:

On the blue summer evenings, I shall go down the paths,

Getting pricked by the corn, crushing the short grass:

In a dream I shall feel its coolness on my feet.

I shall let the wind bathe my bare head.

I shall not speak, I shall think about nothing:

But endless love will mount in my soul;

And I shall travel far, very far, like a gipsy,

Through the countryside – as happy as if I were with a woman.

Arthur Rimbaud, March 1870.

It is worth noting that Rimbaud is in a sense the archetype of the poet-wanderer, bringing unrest, being at once disturbing and captivating; in other words the essence of Wotan, the roving god, guardian of the secret of the runes. The portrayal of the poet as the “god of adolescence” is, in fact, an oversimplification of the modern literary critique. Similar to Odin, the roaming god of poetic inspiration, he is lacking only in warrior frenzy in order to become Wotan.

***

Odin arouses fervour and inspiration. It is fervour itself propelling him and his raging warriors into the “wild hunt”, his arrival announced by the piercing whistle and followed by cacophony, laughter, and noise. He is simultaneously the “wild laughter of life”, as well as the harbinger of storm and pending catastrophe.

However, the term “supreme god” is misleading. There is no doubt that divine ranking is dictated by circumstances, driving particular gods into the shadows, or oblivion, promoting others to the foreground. Certain events will force him to throw his spear and remove his hood, unveiling a golden helmet and a one-eyed face. Having sacrificed his other eye to Mimir, Odin received in return absolute memory, the recollection of everything that once was, that now is and will ever be. It is the moment when Odin will lead his army into the decisive battle, with the fateful outcome known in advance only to him. Only then will it become clear “what he was murmuring with Mimir’s head”.

Jung notes that “apparently he really was only asleep in the Kyffhauser mountain until the ravens called him and announced the break of day”.

The following verses the elusive god utters himself, which becomes clear to any attentive reader of the Voluspa:

Fast move the sons of Mim, and fate

Is heard in the note of the Gjallarhorn;

Loud blows Heimdall, the horn is aloft,

In fear quake all who on Hel-roads are.

Yggdrasill shakes and shivers on high

The ancient limbs, and the giant is loose;

Wotan murmurs with Mimir’s head

But the kinsman of Surt shall slay him soon.

How fare the gods? how fare the elves?

All Jotunheim groans, the gods are at council;

Loud roar the dwarfs by the doors of stone,

The masters of the rocks: would you know yet more?

Wild Hunt #2

Above us the stars are fading

A cry, frightened boughs, a death in the field,

A resonant clash of iron on iron,

Horses in gallop sizing the night.

A gray shadow is a lost, frostbitten

Traveler. Howl – the joy of wolves

approaching the village.

The last lights are dimmed by the wind.

Hands are from bronze,

Night of hand-hammered,

Iron clasps.

We are passing like a wind through the tired fields.

***

(1Founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church; Serbian cultural and religious identity was subsequently built upon his life and works.)

Boris Nad

Translated by Sofia and Aleksandar Stojic