In Solaris (1972), Andrei Tarkovsky presents a vision of contemporary society as one that has become cut off from nature, and provides a narrative that illustrates the possibility of remaining human in the inhuman world that is the result. The film contrasts a life-affirming natural landscape to an urban, constructed landscape where the natural world is submerged and invisible. The Solaris space station is both a projection of this second, inhuman, landscape and an allegory for Tarkovsky’s view of urban life. The narrative of the film concerns the journey by the central character, Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), from emotional deadness to a rediscovery of his humanity as he charts a course between these two worlds, and the role that art, whether painting, music or film, plays in this.

Solaris begins with the leisurely contemplation of a landscape where natural events pass before the camera lens. Water ripples over seaweed, a breeze rustles through a meadow, and in the midst of this is Kris. He stands still, but his eyes move, showing he is aware and attentive to what is around him. His place as part of the natural setting is emphasized by a shot centering on a tree in a field, where Kris enters from the left and crosses the frame in the background, disappearing behind a bush before reappearing, showing him as merely another feature of the landscape.

This immersion in nature reaches its peak when he welcomes and enjoys being drenched by a sudden shower. As Vida Johnson and Graham Petrie note, he is “intimately associated with the sights and sounds of nature – the pond, the trees, the horse, and the dog, his enjoyment of the rain” (Johnson and Petrie 104). The horse in this sequence is particularly interesting, as the meaning Tarkovsky ascribes to horses in his films is straightforward. As he told an interviewer, “for me the horse symbolizes life” (Gianvito 25). Here the horse suddenly appears, with, as Stephen Dillon points out, “no coherent spatial relationship with Kris” (Dillon 15). However, there is a relationship through editing. Kris is seen walking left to right across the frame, there is then a cut to the horse trotting left to right, and then a return to Kris, still walking left to right. The inference through association is that while we soon find out Kris is emotionally dead, his relationship to this setting suggests he has the potential for resurrection.

These opening sequences also serve to predict future events and themes of the film. As Dillon writes, the “watery images with which the film begins recall ahead of time the swirling waters of the planet Solaris” (Dillon 15). This conflation of Earth’s world with Solaris gains further importance in the light of Kris raising the possibility with Berton that one of the options he might recommend is the destruction of the Solaris ocean through bombardment with x-rays, something that would find an echo in the scientist’s plan to blow up the room in the Zone in Tarkovsky’s later filmStalker (1979). So when Kris’ father says that outer space is too “fragile” to have people like Kris making decisions about it, he is also talking about the natural world around them.

In this context, the brief scenes involving Berton’s son gain interest. He arrives from the city, and is soon paired off with a young girl who is never identified and whose presence is never explained (or questioned). She can be seen as a personification of the natural landscape, and her running with the boy and the dog in the rain both a celebration of nature and a precursor to the later connection between Kris and Hari. We later see the boy with the old woman, describing to her being frightened by the horse, the expression of life, and being led back to it as she describes its beauty. This parallels Kris’ later journey which Timothy Hyman describes as “the transformation of . . . initial fear of the ocean . . . eventually into love,” which he argues “constitutes the true narrative of the film” (Hyman 55).

The natural setting shown here is not representative of contemporary society, which enters the film when Kris, after washing his hands in the pond, stands and looks directly at the camera (the audience). What he sees is Berton and his son arriving by car. There is a road running by the side of the property, revealing it to be “an oasis of tranquility in an otherwise ugly environment” (Johnson and Petrie 211).

In fact, this idyllic setting is itself partially a construct. The dacha’s integration with the natural environment is shown during a conversation between Kris’ father and Berton, where the garden remains in shot through a window and the father at one point disappears from the frame and then reappears outside, continuing the uninterrupted conversation through that window and unifying the interior and exterior spaces. But the dacha turns out to be a replica of one that belonged to Kris’ great-grandfather. It is also an imperfect replica, since it has modern gadgets that would not have been in the original, and it is the first of many objects that have been created to recapture something which is lost, all of which turn out to be imperfect. Even here, the modern world is encroaching, the natural world no longer exists as it once did and only through interaction with objects can it to a certain extent be recreated.

The long drive to the city made by Berton and his son presents a contrast between the natural and modern worlds, but also expresses in metaphoric terms Kris’ journey from Earth to outer space and suggests the idealized natural world has been lost. Berton’s trip begins in black and white, following the car through a series of concrete tunnels and overpasses with brief glimpses of trees and shrubbery becoming scarce as the environment becomes increasingly constructed, while sounds of traffic and mechanical noises rise in volume until the car bursts into a maze of freeways and the colours of a garish, neon-lit city at night. As Timothy Hyman writes, the “landscape of these first sequences spells out a polarity between garden and city, organic and inorganic, humanistic and anti-humanistic” (Hyman 55). This polarity is reinforced and broadened by a tempo change as the reality expressed through the studied contemplation of the details of the countryside in the early scenes gives way to the abstract, fast-paced, almost hallucinogenic cityscape, the “stark contrast between the chaotic time-pressure in the technological montage and the tranquil rhythm in the shot of the natural landscape reflects one of the film’s thematic conflicts of technology/nature, space/earth” (Totaro 25).

Contrast edit from (chaotic/modern)….

To (tranquil/rural)

In this way, the journey from country to city is transformed into one from earth to sky. In narrative terms, the actual space flight is somewhat perfunctory, shown almost entirely through a close-up on Kris’ face. An effect much more akin to a rocket launch is achieved early in Berton’s drive by an increase in mechanical sound as the car approaches and enters a tunnel, while the difficulty of interplanetary travel is effectively suggested by the length of the sequence. As C. Claire Thomson writes, the “job of expressing allegorically the unimaginable distance which Kelvin must cover falls to Berton’s interminable drive along all-too concrete motorways and underpasses” (Thomson 9).

This extremely negative representation of the urban landscape is not some future dystopia, it is 1971 Tokyo. Except for a few token gadgets, there is little effort to “futurize” what is shown. As Dillon notes, “we are simply supposed to pretend that this obviously contemporary world belongs to the future” (Dillon 16). The implication of Tarkovsky presenting the present as the future is that it suggests Solaris is not intended as a prediction, but as a critique of the world he saw around him. Chris Fujiwara argues that “Tarkovsky’s films are nostalgic: they view the world as in danger of being lost, and see it from the point of view of someone striving to hold on to it” (Fujiwara 51). However, the film can also be read to suggest the natural world is not just in danger of being lost, but is already gone. Following the trip to the city sequence, the film returns to the dacha, but it is now a black and white world where Kris is burning artifacts of his past, including a photo of his dead ex-wife, Hari. Kris’ father tells him he will make plans “if something should happen” and the old woman turns away and cries, implying this is the last time they will see each other. The tone is melancholic and the lack of the greens, browns and blues of the opening sequence conveys the sense that the journey to the city was also a chronicle of society’s move away from nature, and the film is showing a lost world. The sense of loss and disharmony is emphasized in Kris’ last walk around the dacha. As he passes the open doorway, the horse can be seen trotting by, this time in the opposite direction from Kris.

The space station is an extension of Tarkovsky’s view of the urban world and reflects a lack of interest in the details of space travel that can be summed up in his comment that “for me, the sky is empty” (Gianvito 25). Like the city, the station is a constructed environment where nothing grows. But instead of the dizzying colours of the neon nightscape, it is dreary and run down, the urban landscape by day. What we are shown is the world we live in now that we have cut ourselves off from our roots in the natural world. As Hyman writes, “Tarkovsky in Solaris is clearly talking about our life, today” (Hyman 54). A visual link between the station and the city is made when Kris first enters the station. The hallway is shown in long shot, the dominant chrome-grey colour reminiscent of the tunnels shown in the journey to the city.

Matching chrome-grey tone. Tunnel and…

Solaris space station

The intense unnaturalness of this environment presents a challenge to the three scientists to remain sane. Or, as Tarkovsky has said, “the people in the space station have only to solve one problem: how to remain human” (Gianvito 42). Their response is to attempt to replicate the experience of their former lives on Earth through creating objects (such as the strips of paper attached to air vents that, Snaut claims, at night “sound like the rustling of leaves”) or through the creations of others, works of art such as the Breughel paintings that hang on the walls of the station library. Interestingly, the library also has a bust of Plato, a copy of which also could be seen in Kris’ father’s dacha. Plato’s belief that everything on Earth was merely a false, illusory duplication of an “ideal” form (in Heaven) is echoed in the series of flawed imitations we are shown. Indeed, even the dacha with the “original” bust is itself an object constructed to replicate a lost experience, which will be (imperfectly) replicated again later in the film. These are all imperfect replicas: the rustling paper or a Breughel canvas are not the same as actually being in a forest, and the butterfly collection on Snaut’s wall is not the same as a real living butterfly, but they offer the possibility of providing connections to human experience.

Tarkovsky writes that “art is a meta-language, with the help of which people try to communicate with one another . . . this has not to do with practical advantage but with realizing the idea of love” (Tarkovsky 40). In light of this, it is possible to see Hari as a work of art. Like a Breughel painting, she is an imperfect replica of something lost, and through interaction with her, Kris rediscovers what it is to be human and to love. This is the key difference between the film and Stanislaw Lem’s original novel, which was a critique of the idea of anthropomorphically ascribing human values to a universe possibly organized in a manner beyond human comprehension, and in which these values are probably meaningless. As Johnson and Petrie write, “Tarkovsky’s film, by contrast, is a celebration of human values and of the power of love in an indifferent or hostile universe” (Johnson and Petrie 102). They note further that Kris’ transformation under Hari’s influence is visually charted as the white spacesuit, which “initially associates him with the coldly geometric layout” is replaced by grey sweater and slacks (Johnson and Petrie 108). In fact, it goes much further than this. As the relationship between Kris and Hari becomes more intense and they both become more “human,” their clothes seem to be progressively stripped away and we become more aware of their bodies until, during Hari’s suicide attempt and resurrection, which is when they are at their most human, Kris is in his underwear and Hari wears a transparent negligee through which her naked body is clearly visible.

It is in the levitation sequence that the interaction between Hari, the replica of a human, the replications of human experience (which is a possible view of painting, music and film) and Kris, the human, reaches a climax. There are a series of cuts between Kris watching Hari, Hari staring at Breughel’s “Hunters in the Snow,” camera pans of close-up details of that painting and flashbacks of the home movie of Kris as a child in a snowy landscape that they watched earlier. Suddenly, the period of weightlessness begins. First candles begin to float, then the chandelier ripples with sound, and Kris and Hari begin to float as the Bach Prelude heard at the beginning of the film and during the showing of the home movie returns, an evocative work of art “associated with Earth and its values – nature, art, love” (Johnson and Petrie 108). As they levitate, the camera cuts twice more to “Hunters in the Snow” as Hari also begins to take in the other Breughel paintings. It seems to be a moment of transcendence, even exaltation, in a way reminiscent of the balloon flight at the beginning of Andrei Rublev (1966). And when it is done, they relax on the ground with Kris’ head on Hari’s lap, and it is almost as if they have just had sex. There is then a shot of the swirling Solaris ocean as electronic noises rise and overpower the Bach. This is followed by the sound of a crash and a sudden cut to the smoking vial, as Hari has just tried to commit suicide. A way of reading this scene is that through the evocative power of Breughel’s snowscape, Hari is able to relate it to the home movie of young Kris in the snow, and she is able to understand what being human means and to fully love Kris. As Hyman writes, “when she turns to Kris, we realize through Breughel she has been able to apprehend what it is to be a human being on earth” (Hyman 56). The shot of the Solaris ocean in tumultuous activity which follows reinforces this, as if the synapses of a giant brain are popping frantically as it assimilates information.

That Hari’s understanding of what it is to be human is followed immediately by a suicide attempt is not a contradiction. Johnson and Petrie see it as an act of love, that the “new Hari’s sacrifice is a redemptive one from which Kris is able to learn and benefit, rather than a gesture of despair,” which the original Hari’s suicide had been (Johnson and Petrie 105). Dillon has a different interpretation. Relating it to his reading of Solaris as a reflexive meditation on cinema, with the relationship of Kris and Hari analogous to that between audience and film, he suggests the “levitation is beautiful but temporary. Their time together is really one manner of disorientation after another . . . This scene does not imply the “naturalness” and “timeliness” of art, but instead the ghostly artifice of art” (Dillon 14). He goes on to write that “the next sequence begins with the revelation that Hari has drunk liquid oxygen, further eroding any idealistic reading of the levitation” (Dillon 14). This is a problematic reading because it ignores what is expressed in so many of Tarkovsky’s films, that for love, “the meaning . . . is in sacrifice” (Tarkovsky 40). Hari’s ability to make the ultimate sacrifice is a sign of hope because it proves that even on the space station, and therefore in the soulless contemporary society, it is possible to act as a human, and that this gaining of humanity is possible through interaction with art. That it requires a non-human (Hari) to instruct a human (Kris) on being human adds a layer of irony to the situation. Tarkovsky’s intention seems similar to how he describes a transcendent moment fromCries and Whispers (1973, Ingmar Bergman) where Bach is also used, that “even this illusory flight gives the audience the possibility of catharsis, of that spiritual cleaning and liberation which is attained through art” (Tarkovsky 192).

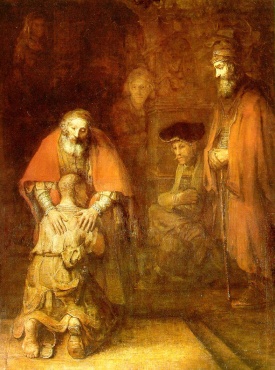

The “death” of the replica Hari is then followed by a finale in which Kris seems to return to the dacha and kneel for his father’s blessing in a pose taken from Rembrandt’s “Return of the Prodigal.” This suggests that Kris, now emotionally resurrected and painfully aware of the new Hari’s absence, has embraced the humanistic beliefs of his father which he had been skeptical about in the opening section. This is a replica Kris on a replica dacha, like the original dacha an island in an otherwise completely different landscape, in this case the Solaris ocean. It is also another imperfect replica, as the water does not ripple and the rain falls inside the dacha instead of outside. But it still reflects the transformed Kris. As Tarkovsky says, Kris “has been recreated by the Ocean – the materialization of his homesickness has been taken from him and reconstructed on the planet” (Gianvito 72). This is another major change from the novel, where Kris travels to the planet and is left standing on an indifferent ocean, a consciousness he will never connect with (Lem 211).

Rembrandt’s “Return of the Prodigal”

According to Tarkovsky, the controlling idea of Solaris is that “human beings have to remain human beings, even if they find themselves in inhumane conditions” (Gianvito 136). In terms of the plot, these inhumane conditions are on a distant planet, but what the film tells us is that today we live in a time where the natural world has been paved over by a modern, constructed one and there has been a “total destruction in people’s awareness of all that goes with a conscious sense of the beautiful” (Tarkovsky 42). In this situation, it is through interaction with art (which, as mentioned, deals with “realizing the idea of love”) that modern man can remain human. Solaris is about the world Tarkovsky saw around him.

Works Cited

- Andrei Tarkovsky Interviews. Ed. John Gianvito. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

- Dillon, Steven. The Solaris Effect: Art & Artifice in Contemporary American Film. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006.

- Fujiwara, Chris. “Solaris.” Cineaste 29.3 (Summer 2003): 51.

- Hyman, Timothy. “Solaris.” Film Quarterly 29.3 (Spring 1976): 54-8.

- Johnson, Vida T., and Graham Petrie. The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994.

- Lem, Stanislaw. Solaris. New York, NY: Berkley Publishing Corp., 1971.

- Tarkovsky, Andrei. Sculpting in Time. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1987.

- Thomson, C. Claire. “It’s All About Snow: Limning the Post-Human Body in Solaris (Tarkovsky, 1972) and It’s All About Love (Vinterberg, 2003).” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 5.1 (2007): 3-21.

- Totaro, Donato. “Time and the Film Aesthetics of Andrei Tarkovsky.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 2.1 (1992): 21-30.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login