Not only in his time but in present day, Michelangelo Antonioni’s style of narration is considered unique and inimitable. There is something about his films that make all the different narrative spaces of his stories recognizable, regardless the language the characters are speaking or the landscapes they are roaming.

Whoever the actor, whether it’s Jack Nicholson, Marcello Mastroianni or David Hemmings, you’ll know that the film you’re watching belongs to this great filmmaker, and you’ll recognize his voice through these actors’ words. What comes below lists only some of the most noted visual and sonorous elements of his cinema.

Being familiar with architecture, Antonioni has mostly represented the architectural concepts through cinematography, so most of the elements mentioned in this text are actually mirroring back this very notion; the mentioned narratives are utterly based on the idea of unifying the character and the surrounding ambiance. In Antonioni’s cinema, dramatic development of the story and the character’s treatment both take form through placing the character in a specific landscape.

As always, if you think you can add to this list, don’t hesitate to recommend additions.

1. Dominant narrative ambient

The most significant choice in Antonioni’s narratives is initially choosing the right landscape. Specifying ambient details such as where, when and why the story is happening assists the story’s development. The answers to these questions can be explained in the case of “Blow Up” (1966).

The story takes place in London. There’s a vast range of urban, industrial landscapes to choose from, and that very fact that can also assist in giving a sense of rationality to the character and the city. The colors are flatter, the light you can get in London (while it’s not raining of course) is perfect for the kind of photography the character (and consequently Antonioni himself) uses, which is fashion photography.

It is objective photographic documentation in some cases and this is the exact mode of visual and sonorous treatment Antonioni chooses to approach his characters and their stories. By just by choosing London as your location, what you get is flat, low contrasted light and urban rationality. The story takes place in the 60s and no other city but London can mirror the social situation of this period of time.

The choice of the main location for a cinematic story is maybe the most crucial one for the filmmaker, for this very element is the most basic reference to the world we’re living in. By relying on what the audience actually knows or has heard from London, the filmmaker ushers the audience into the narrative. This is the same very narrative role of the island in “L’avventura” (1960), the urban suburb life in “L’eclisse” (1962), and the Grand Canyon in “Zabriskie Point” (1970).

2. Alienation

Isolation of the character is a repetitive concept in Antonioni’s cinema. His characters are hard to sympathize with, as they do not represent a majority. Antonioni’s main characters are loners, standing outside of social norms such as family or friendship. These protagonists, even if they have a family, friend or lover, may be on the verge of losing them.

Isolation of the character is a repetitive concept in Antonioni’s cinema. His characters are hard to sympathize with, as they do not represent a majority. Antonioni’s main characters are loners, standing outside of social norms such as family or friendship. These protagonists, even if they have a family, friend or lover, may be on the verge of losing them.

“La Notte” is the story of a couple whose love is long lost. “L’eclisse” is about a couple who find each other and seem to be perfect for one another, and they leave each other in a hopeful state, promising an appointment for the same afternoon; however, they never attend the date. The protagonist of “Blow Up” finds his wife in bed with his friend.

Monica Vitti in “L’avventura” takes the place of her best friend and starts a relationship with her boyfriend, while in “The Passenger”, the protagonist and his wife are simply geographically too far from one another to be considered “a couple”. These loners rarely share their secrets, and the emotions in these stories tend to remain inward.

What Antonioni tries to describe is a tough challenge. There are unspoken words in these films, if there’s an emotion or a feeling or in general a subjectivity that has to come out of the narrative context, the only way to show it is through juxtaposition of the pictures and situation.

If Bresson counted mostly on the succession of images and sounds to recreate a feeling, Antonioni more than anything else has achieved the same aim through creating a narrative ambient, using the architectural surrounding space and moving the recitation of his characters inward.

3. Diegetic music

[vsw id=”ItDmn40TvuI” source=”youtube” width=”483″ height=”402″ autoplay=”no”]

In almost all of Antonioni’s films, the music has an actual existent source in the location. In “Blow Up”, apart from the initial and final music that accompanies the titles, every other musical score is audible through an existing source on set: a radio, a stereo, or a concert.

Music in his films is only another element to construct the narrative ambiance; it’s not some superior element that commands the audience the feeling that the scene ought to show. The music is just there, not just coming from an outside source.

4. Architectural presence of urban life

The half-finished buildings, tall walls and angles are visually like bricks to Antonioni, material to construct his perfect architectural and photographic composition of every single shot. The idea of using the characters as materials of this whole architectural composition is dominant in Antonioni’s cinema, except that this very element is capable of moving and passing through spaces.

The concept of “abandon” repeats itself in the choice of urban suburbs, an isolated house that oddly has no neighboring house around, or an industrial landscape with deserted alleys where the character has to yell out to see inhabitants. All these spaces reflect the state of mind of the character and form an essential part of the character’s development. In Antonioni’s cinema, the treatment of the character is no different from the treatment of the narrative space.

5. Referring to sound-effects, cinematic soundscape

[vsw id=”3K3yv99b2z0″ source=”youtube” width=”483″ height=”402″ autoplay=”no”]

The use of sound effects in Antonioni’s films is quite different from how Bresson uses sound effects in his cinema. While Bresson utilizes sound effect as a reference to action that is happening out of frame, in Antonioni’s cinema sound as any other expressive element is used to construct a whole narrative ambient and complete the final architectural image.

Once again, we have to remind ourselves of the fact that any movable or motionless, visual or sonorous element in his cinema is severing as a constructive component of a cinematic narration as an architectural representation. The kind of soundscape Antonioni is expecting in London is quite different from the cinematic soundscape he gets from the island in “L’avventura”. Ambient sound is a composition of meaningful detailed existing sound effects in that very location; undoubtedly in any of these locations the unwanted element has been eliminated.

The park ambiance in “Blow Up” is simply the sound of wind blowing through a mass of trees, there is no doubt that in that park (specially a park located within a city) one can hear lots of other ambient sonorous elements, but the sound of a mass of trees moving in the wind gives a rustling hum that assists again in isolating the character and the narrative space from its surrounding ambiance. Specifically, one can note the fact that the park is the most significant ambient in the whole narration.

6. Thresholds

Almost repetitively, Antonioni’s characters look in or out through the threshold of some kind of entrance, whether it’s a door or a window. This mode of framing the character is a way to describe the existent distance between two subjectivities, defining an internal space as an intimate territory of one specific character, making any other character an invasive figure.

There are numerous examples of framing a character in the threshold in “Il Grido” and the final sequence of “Profession: Reporter” can be a perfect example.

In “L’avventura”, the scene where Monica Vitti (Claudia) looks in while waiting outside of house for her friend is a meaningful mise-en-scène. She’s located outside of an intimate relationship between Sandro and Anna; the dramatic weight of the scene gets more notable as the narrative flows, as Claudia starts a relationship with Sandro and practically takes the place of her missing friend.

7. Eliminating color to emphasize form

“Blow Up” is in color, while the photos where the character is searching for a sign of “the incident” are in black and white. It’s a mode of flattening the whole visual context and then only bringing out one element that formally and visually stands out.

Even if some works of Antonioni are in color, they are mostly de-saturated. Representing a low contrast picture and flattening the visual texture is a notable element in Antonioni’s filmmaking style.

8. Photographic compositions/the importance of background

Whatever is in the background in the shots of Antonioni’s films, it’s by no means a passive background. In “Blow Up”, as the profession of the character justifies it, the characters generally stand before a plain colored surface.

In “Blow Up”, Antonioni has used this fact as visual assistance in representing and developing the unspoken characters. Jane (Vanessa Redgrave) has lots of secrets, though apparently is ready to start an intimate relationship with Thomas (David Hemmings), because he is now the one she’s unwillingly sharing her gravely important secret. She doesn’t even reveal a word of her past or the incident in the park.

Nonetheless, Antonioni’s mode of representing Jane’s character is a plain violet paper screen that Thomas chooses as her perfect color, while the rows of models who are covered with colorful customs and makeup. The background is a layer of transparent surfaces, and the young girls who don’t have a specific color and just roll in the colored screens, can tell a lot about the indecisive and still unformed characters of the girls.

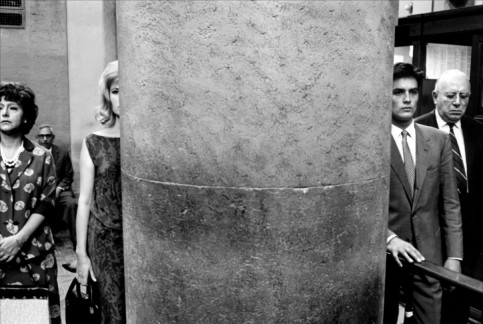

9. Blocking the figures

Instead of getting closer to a character to take a close up or cutting the whole figure of the character, Antonioni keeps blocking their aspects with an architectural element, like the column that blocks the full shot aspect of Alain Delon and Monica Vitti in “L’eclisse”, or the row of models in “Blow Up” where each model blocks the one behind her. This fact can be easily interpreted as the part of character that doesn’t come out or is not freely expressed.

Gus Van Sant uses the same narrative method to get closer to his characters, which is specifically notable in “Gerry” (2003) as he prefers to restrict the visual camp instead of physically getting closer to the subject.

10. Absence

[vsw id=”SHUapLYEi4s” source=”youtube” width=”483″ height=”402″ autoplay=”yes”]

After introducing the character in an ambient setting, Antonioni keeps eliminating the presence of the character to create the sense of absence.

Much like showing a corpse in the park, later for it to disappear unexpectedly, or introducing a character as a main character that gets lost at the very first sequences of the film (“L’avventura” and most importantly, the final scene in “L’eclisse” where the characters do not show up at the appointment). It’s all about what the filmmaker decides not to show or narrate and leaves it as an open choice to his audience.

There’s this perfect scene of the couple biding their time in a night bar that says it all about Antonioni’s philosophy. Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni) and Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) are just sitting there, wordlessly watching an odd performance from a dancer who dances with a glass of wine without wasting a drop. This is a conversation scene, only the subject of the conversation is the thought that Lidia has and doesn’t want to talk about it.

The dialogues reveal the fact that there is something that the character refuses to utter. This conversation is what real life is: it’s boring with lots of points that remain silent and maybe they won’t be ever expressed. What the audience expects from cinema is the dance of the woman with the glass of wine. What Antonioni is trying to say in this scene is this: you want to be entertained? I give you a circus; but the silent tiresome is real life, it still remains in the background and nothing is going to change that.

David Zou

You must be logged in to post a comment Login