[wpedon id=”3579″ align=”center”]

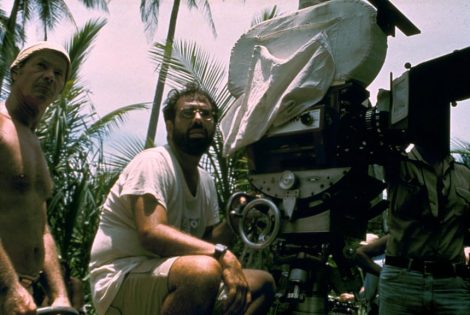

Everyone in the house at the Beacon Theatre already knew the legend of Apocalypse Now. The troubled production of Francis Ford Coppola’s psychedelic Vietnam war epic has already calcified into the stuff of industry myth: leading man Martin Sheen was nearly felled by a heart attack, second lead Marlon Brando showed up to set too overweight to believably portray a Green Beret, a monsoon seemingly sent by God destroyed thousands of dollars in equipment. The behind-the-scenes documentary Hearts of Darkness tracks Coppola’s descent towards madness during the unending shoot in the Filipino jungle, the money and pressure and humid South Pacific air all getting to him. (The film-maker joked: “It could’ve easily been called Watch Francis Suffer.”)

For Coppola, however, last night’s Tribeca film festival premiere of the new and definitive Final Cut – commemorating the 40th anniversary of the original release – offered him a chance to rewrite his own history. He’s gone back in to edit the film once before, assembling the 202-minute Redux version in 2001 using scenes excised from the theatrical cut at the behest of the studio and other higher-ups. The just-right Final Cut splits the difference between the creative concessions of the original and the unwieldy sprawl of the Redux, a massive feat of film craft reined in to the general neighborhood of perfection.

Curious parties will be relieved to know that only the choicest Redux additions have earned the spruced-up picture and audio of the Final restoration. An extended tangent bringing Sheen’s unstable Captain Willard to a French plantation made the cut, perhaps due to Coppola’s affection for his late son Gian-Carlo, who appears as a nobleman’s boy at dinner. A comic interlude involving Willard’s men purloining the surf board of the gruff Lieutenant Kilgore (Robert Duvall) also remains in place. The same cannot be said for the scene in which the squadron encounters a downed helicopter containing the Playboy bunnies from an earlier USO show, and trades them two tanks of fuel for two hours with the girls.

Coppola has at last gotten everything right where he wants it, which testifies to the real evolution of this project, as an insane risk that gradually vindicated everyone crazy enough to have believed in it. During the post-screening Q&A with Coppola, moderator Steven Soderbergh sounded almost baffled that someone with two best picture wins and a Palme d’Or under his belt would have so much trouble getting his masterpiece green-lit. But Coppola faced opposition at every stage to his unhinged vision, ultimately putting himself on the hook for $30m while publications gossiped about its calamitous delays with “apocalypse when?” puns.

“I realized that if you have success as a Hollywood film director, the next film you do has to be similar to the ones you had the success with,” Coppola said. “At that point, my wish as a relatively young director was to make as many different styles of movie as I could … What good is success if you can’t make the kind of movie you want to?”

He may have been one of the most well-regarded artists in his field, but Coppola was still an underdog, up against the odds from start to finish. For an audience hanging on his every word, he recalled mangling his Oscar statuettes in a fit of anguish (his mother later got the Academy to replace them), and regaling his despairing crew with a riff on a classic show tunefrom Damn Yankees.

“I went to them, and I said, ‘A good screenplay, we haven’t got. A good movie, we haven’t got. A good director, we haven’t got. What’ve we got? We’ve got heart!’”

Last night, whatever opposition this film once faced was a distant memory, as Coppola dispensed wisdom from the right side of posterity. “If you want to make art,” he said, “you have to be comfortable with risk, and taking a chance that you know best.” Soderbergh put it even more succinctly: “I don’t know what to say, other than that you gambled and you won.” Coppola beamed at the instant round of applause, surrounded by irrefutable evidence that he had made the right decisions, even if they seemed crazy at the time. They say textbooks are written by the victors, and because he just so happened to be a genius with talent too great to be denied, Coppola now gets the privilege of setting his own legacy. His parting words, by no coincidence, sounded like they came from a god.

“In film-making and in life, extraordinary things happen to you, and it’s up to you to make them be positive. Because the good news is that there is no hell, and the quasi-good news is that this is heaven. Don’t waste heaven.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login