On Sunday, May 06. Radiohead bleached its Internet presence—its Web site faded to white; its Twitter and Facebook pages were scrubbed of content—a move so blatantly counterintuitive that acolytes knew to recognize it as a portent. The week prior, inscrutable paper leaflets had been stamped and shipped to some fans, embossed with the band’s toothy-bear logo and the words “Sing a song of sixpence that goes / Burn the Witch / We know where you live.” A new album: it is surely nigh.

Plucking an enigmatic postcard with the phrase “We know where you live” from the dark recesses of your home mailbox might alarm anyone unfamiliar with Radiohead’s elaborate, vaguely playful approach to the album rollout. Since the mid-two-thousands, the band has reconfigured record promotion as a kind of oddball scavenger hunt, embedding unlikely clues in unlikely places, a method that’s been adopted by younger bands like Arcade Fire. (Whether you find it pretentious or pleasurable might have something to do with your tolerance for extra-musical shenanigans.) On Tuesday, Radiohead released the video for “Burn the Witch,” also the presumptive title of its new record, and a song that has existed, in one form or another, since the sessions for “Kid A,” in 2000.

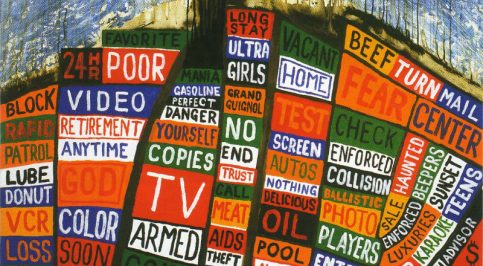

The phrase is a familiar refrain for those intimate with the band’s catalogue (the words “Burn the Witch” appear in the album artwork for “Hail to the Thief,” from 2003, and Yorke has repeatedly teased bits of the song’s lyrics online) but it functions now as more than a mere shibboleth, a password murmured knowingly among the devoted—it’s become the pithy encapsulation of a political ethos the band has been rallying against for its entire career. The demonization of the Other, the slow eradication of the marginalized or misunderstood: from its outset, Radiohead aligned itself, always, with the afflicted. “I’m a creep, I’m a weirdo,” Thom Yorke sings on the band’s first single, “Creep.” “What the hell am I doing here?”

That message—an expression of devastating self-doubt, and an inadvertent indictment of a cultural system that nurtures alienation—is omnipresent in the band’s catalogue. One could argue that Yorke’s lyrics have become more explicitly political (and less concerned with his own worried narrative) over the last decade, although it seems just as easy to argue that those approaches are, in fact, inevitably braided. In many ways, Radiohead has been our century’s most prescient political group. The band’s ideas about the toxicity of political hegemony and mass disaffection (in particular, the various ways technology, as employed both by ourselves and our governments, can leave us feeling hostile and estranged) seem to have reached a terrifying apex of late. Radiohead’s twitchy, anxious melodies express true apprehension about the future: both where we’re going and, more important, how we’re going to get there. Palpable dread is built in to Yorke’s ghostly yawp; his voice moves through these songs like a cold wind. There is no other singer I can think of who is better or more practiced at bodying existential duress. “This is a low-flying panic attack,” Yorke declares on “Burn the Witch.” All of Radiohead’s best songs are just that.

[vsw id=”yI2oS2hoL0k” source=”youtube” width=”465″ height=”384″ autoplay=”no”]

Yorke once gave wild voice to the dispossessed (“I’m not here, this isn’t happening,” he moans on “How To Disappear Completely,” from “Kid A,” a lyric so suffused with grief it’s hard not to press your hands over your ears), but now he’s assumed the point of view of the autocrat, the bully: “Avoid all eye contact, do not react, shoot the messengers.” The stop-motion video for “Burn the Witch” is set in a whimsical village where ordinary-seeming human beings do horrifying things to each other for reasons that remain largely unclear, except that they appear to be following the guidance of a demagogue-like figure, dressed in a uniform and medallion. The clip seems inspired, in equal parts, by the British children’s series “Trumpton” (the name of which does not feel coincidental), and the horror film “The Wicker Man,” from 1973. In an interview with Billboard, one of the video’s animators, Virpi Kettu, suggested that the action of the piece—in which a cabal of men wearing antlered masks surround a woman bound to a tree trunk, and a man is coerced into climbing inside a giant wooden effigy, which is then set on fire—might have something to do with the refugee crisis in Europe. Regardless of the video’s precise impetus, the broader thesis is clear: the moment we stop asking questions of authority, we become cogs in a monstrous and dehumanizing machine. We ruin each other.

Although the band’s first two releases, “Pablo Honey” and “The Bends,” are guitar-forward in obvious ways, Radiohead has since come to (mostly) eschew the instrument, or at least circumvent it, and “Burn the Witch” is anchored by its antsy, rhythmic string section and groaning synthesizers. About a minute in, Yorke’s voice moves to the forefront, and he unleashes that surreal, speeding wail—as frantic, careening, and hopeless as a moth zooming endless circles around a streetlight.

Earlier this month, the band’s producer, Nigel Godrich, tweeted a photo of what appeared to be a yellowing page from “The Plot Genie Index,” a compendium, published in 1936, of disembodied plot points. (“Now you, too, can write pulp fiction!”) Godrich’s index finger is hovering deviously close to No. 170 on the book’s sixth list of “Problems”: “Obliged to risk fortune in an effort to put down a rebellion.” The rebellion in question is not specified, but the implication—that circumventing it will be costly—feels germane to Radiohead’s entire marketing strategy. Yorke has expressed skepticism about the efficacy and ingenuity of streaming (in 2013, he referred to Spotify as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse”) and has since initiated several intrepid efforts to pluck his music from those catalogues, with varying degrees of success (the six studio albums Radiohead released prior to “In Rainbows,” in 2007, were created under the auspices of Parlophone Records, then a subsidiary of EMI, which was acquired by Warner Music, in 2013). When the band self-released “The King of Limbs,” in 2011, a record comprised largely of samples and loops, Yorke stood on a street corner and handed out copies of a newspaper—possibly the most aggressively analog form of media still extant—that included relevant artwork, lyrics, and stories. (The British music magazine NME later described its contents as “trees, pictures of trees, and thoughts about trees.”) The band has always had a complicated relationship with technology—either embracing it, or vilifying it, or both.

Technology does cut two ways: it facilitates a weird and sometimes useful intimacy, sure, but it also teaches us to conflate a curated identity with a real one, and, moreover, to work on perfecting our systems of curating rather than our actual selves. This becomes important, politically, when we can no longer read or understand the human character. Our present cultural climate discourages empathy—a stay-in-your-lane policing has been afoot for a while now—and demands the performance of absolute authority. The idea that a person could work to understand another, to assume their struggles and their triumphs, to question them, and to love them regardless, is the crux of any spiritually functioning civilization. Yet this seems to be Radiohead’s real anxiety: that we are all forgetting how to know each other, and how to be properly alive.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login