The grid system which the Roman republic exported all over Europe was never employed in the capital itself. The city has always lacked a coherent plan – save for the monumental temple that once towered over it.

According to Tacitus, perhaps the greatest of all Roman historians, it was the great temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill that held the key to the future of ancient Rome.

Writing about a fire at the temple in AD69, Tacitus assumed the conflagration would embolden the enemy Gauls into thinking they might finally conquer the city, such was the symbolism of the temple. “This fatal conflagration has given proof from heaven of the divine wrath,” he wrote, “and presages the passage of sovereignty of the world to the peoples beyond the Alps.”

But Tacitus’s fears were not realised. The Gallic revolt was crushed and the temple rebuilt – as it was again and again right up until its closure by the Christian emperor Theodosius I in AD392. Indeed, even after Roman power had shifted to the east, and the Vandal invasion of 455AD had stripped all gold from the doors of the temple, the prefect of Italy, Cassiodorus, was moved to write: “To stand on the lofty Capitol is to see all other works of human intellect surpassed.”

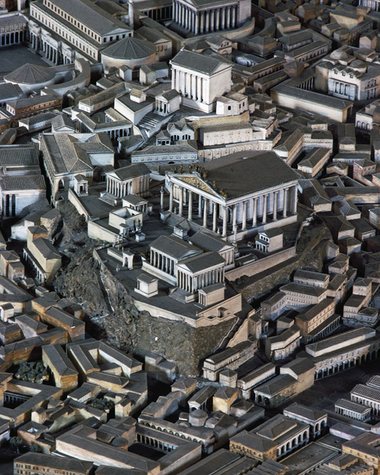

This focal point above the city was begun nearly 1,000 years earlier by Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last Roman king – but only completed and dedicated, according to legend, in the year of his overthrowing and the creation of the Roman republic in 509BC.

It was a massive structure for its time – the largest temple in the Italo-Etruscan world – standing on a stone plinth measuring 53 by 63 metres, and with a broad red roof supported on 24 columns. Also known as the temple of the Capitoline Triad, inside were statues of the three gods most venerated by the Latin people: Juno, Jupiter and Minerva. On the apex of the roof was a quadriga, a blatant symbol of martial triumph depicting four horses being driven by Jupiter himself.

“Here was where the Roman kings established the centre of its most important cult: the temple of the Capitoline Triad – Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno Regina and Minerva,” says Prof Filippo Coarelli from the University of Perugia. “They were hoping to draw the political centre of the Latin League [a confederation of about 30 towns mainly south of the Tiber] to Rome and displace the league’s traditional cult centre on Mons Albanus – present-day Monte Cavo.”

According to Dr Robert Coates-Stephens, a fellow at the British School at Rome, the temple inspired a sense of destiny and invulnerability: “The Romans considered the Capitol important because it was home to the state religion and because, according to optimistic tradition, since the hill failed to be taken by the Gauls in 390BC, it had always remained inviolable.”

The temple building was copied across the Roman empire as the focal point of new settlements or of old enemy cities that were embracing the Roman way of life. It is telling that when Constantine built his new eastern capital on seven hills along the Bosphorus in AD330, he removed the colossal statue of Hercules that stood in front of the Temple of the Triad to confer legitimacy on his new Capitolium.

Indeed it might be said that, had the Romans not succeeded in focusing the Latin League on this temple, Rome may not have achieved its domination of the league. And without that, we would not have had the Roman empire, one of the most influential forces in the development of urbanisation there has ever been.

The selection of the site on which Rome was founded in the eighth century BC is the stuff of myths. Whether it was Romulus and Remus, Virgil’s Aeneas or one of the early Etruscan kings who founded the city hardly matters, as the reasons for choosing this hilly bend on the river Tiber were obvious.

“Rome is at the lowest point on the course of the Tiber where the river is naturally crossable, and like many important ancient or medieval cities (think of London) Rome is close to the sea, but not close enough to be in serious danger from pirates,” explains Georgy Kantor, associate professor in ancient history at St John’s College, Oxford. “Also this was the point where Via Salaria, the Salt Road, leading to important salt pans inland, joined the main coastal road.”

As well as creating a spiritual focal point devoted to victory on the Capitoline Hill, the kings also drained the malarial marshes between the seven defensible hills of Rome so that people could meet and trade. Additionally, during the reign of the penultimate king, Servius Tullius (who reigned 578-534BC), they completed a wall round the hills to keep this huge city safe.

“By the late sixth century BC, the city of Rome had united around a central space, surrounded by a defensive wall and in the shadow of a temple which was one of the largest in Italy, and by its simple monumentality an indication of Rome’s importance,” says Prof Christopher Smith, director of the British School at Rome.

Because of the policy of making trading allies of its defeated enemies, money flooded into Rome in the early days of the republic. The city that sprung up below the temple of the Triad was a hodgepodge of narrow streets and tall wooden buildings with forums and markets created by individual donors.

So was there any guiding principle behind the development of Rome? Certainly, there was no Dinocrates of Alexandria to lay out the city for the first kings and their republican successors. But according to the Roman historian Livy in hisAb Urbe Condita, the early Etruscan kings did try for rational urban planning of the kind found at Rhodes, Pella, and Philippi – but all that was swept away when the Gauls sacked Rome (390BC) and by the unbridled speculative building that followed.

In 63BC, the great orator Cicero lamented the discrepancy between the regular planning of Roman cities in Campania, with the hilly and swampy conditions in Rome itself.

The lack of any effective urban plan is shown in the way that a victorious general, after processing in triumph up to the temple on the Capitoline Hill, had the right to build a new temple wherever he chose – and in the way that wealthy politicians such as Julius Caesar would build a marketplace to curry favour with the people. Pompey built a theatre to honour himself, and Sulla a new state archive.

This level of individualism was both Rome’s strength and weakness. When most of Rome burned down under emperor Nero in AD64, Tacitus chronicled how a new plan for stone buildings at a standard height with wide streets was drawn up – but reported that the people lamented the lost, ad hoc nature of republican Rome.

“Still, there were those who held that the old form had been the more salubrious, as the narrow streets and high-built houses were not so easily penetrated by the rays of the sun,” he wrote, “while now the broad expanses, with no protecting shadows, glowed under a more oppressive heat.”

In 1563, England’s Queen Elizabeth I coined the Latin phrase “Romam uno die non fuisse conditam” (Rome wasn’t built in a day). She might have also added: “And it was hardly planned at all.”

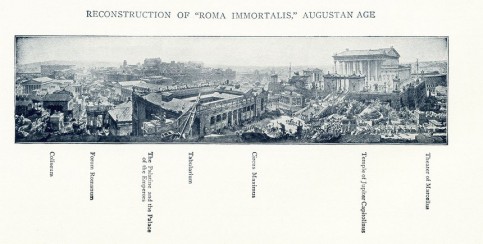

Today, the Rome of the republic lies buried beneath medieval and renaissance Rome. It further disappeared under the 19th-century expansion that followed Italian unification in 1871. Those famous seven hills have been levelled and built over to the point that their obscured contours have merged with the rising level of the valleys below.

Indeed, you could be forgiven for not realising that a marshy valley once ran between the Capitoline and Palatine hills. The only reason we can see this valley at all today is because in the 1930s, Mussolini demolished more than eight acres of buildings and removed rubble lying 20 feet deep to expose the forum.

Ancient Rome – the powerful, republican city that so rapidly conquered the known world – has, of course, given us so many ideas about urban planning. Today we talk about capital cities and forums, as well as structures such as amphitheatres, basilicas, metalled roads, pavements and multi-storey apartment blocks because of the idea of the city that Rome bequeathed us.

Yet it is ironic that the grid system (what the Romans called centuriation), a city planning concept they exported all over Europe from the third century BC onwards, was never employed in Rome itself. The Romans got their idea of laying out their cities on a square grid from the military encampments they constructed on campaign, but it was never possible to implement it properly in Rome because of the power of individual initiative – and, of course, those hills.

After the empire moved its capital to Constantinople in AD326, everyone who could afford to leave Rome followed suit. The city was repeatedly looted and only began to recover some its lost significance during the Renaissance, and with the return of the popes. It took until the 20th century for it to regain its ancient proportions.

Nevertheless, the temple of the Triad lasted until AD1536 when its remains were demolished as part of a palace and piazza development conceived by Michelangelo for Pope Paul III. What is left of it is now under Michelangelo’s Palazzo dei Conservatori, one of the Capitoline Museums. These days, you can see some of its mighty plinth exposed if you walk up to the first floor.

Rome remains a hodgepodge, one of the worst examples of the very notion of the well-planned city, an idea that it bequeathed to us via – among others – Chester in Britain, Verona in Italy, Trier in Germany and Sinop in Turkey. But the impact of its Temple of the Triad can still be seen now if you stand down in Mussolini’s reconstructed forum and gaze up at the Capitoline museums.

As for the idea of the Capitoline Hill, that reached eventually as far as America where today there are nine Capitol hills across the United States, including the seat of the US congress in Washington.

Adrian Mourby

You must be logged in to post a comment Login