It’s amazing to think of the vast methods one can use to structure a story. Depending on the narrative itself, you could distort the structure any way you deem necessary, considering the structure enhances the story.

Whatever structure the writer decides upon, all good stories fundamentally follow the basic three-act structure. From then on there’s a vast number of styles and structures that can be chosen to make sure a story hits its mark.

Any good film inherently starts with a good story, whether it’s a basic concept, character or theme. From then on the story informs the genre, style, pace and structure. No matter how genius your structure is, it means nothing if it doesn’t correlate with the story.

One thing that’s interesting about life is that everything and everyone rest’s on point of view. Whether it’s religion, music, politics or the philosophy of life, our beliefs and opinions rest solely on our point of view. Our points of view form from all our life experiences and influences.

The same holds true for any work of art; we’re given the point of view of the artist. We don’t have to necessarily agree with it or understand it, but we have to see that it has a point.

With cinema, the audience is given the point of view of a character/s and is therefore forced to pick a side. I mention this because point of view plays an important part of structuring a story. How the characters perceive things or how the writer wants the audience to perceive his work depends on the relationship between structure and point of view.

With that in mind, we look the different ways writers and filmmakers have structured films, why these structures are used, and the relationships with the point of views in hand.

10. The Usual Suspects (1995)

“The Usual Suspects” perhaps has one of the most famous twist endings in the modern cinema next to “The Sixth Sense” and “Fight Club.” Successfully turning a story on its head is one of the hardest things for a filmmaker to do, and requires immaculate story building to deliver the big payoff.

The film features an anchoring performance from the recently shamed Kevin Spacey, who plays a small-time con man, who recounts a convoluted story to police interrogators of a heist gone wrong, commissioned by a mysterious mob boss known as Keyser Söze.

Like the other famous twist endings previously mentioned, they mostly rest on one character’s point of view, otherwise known as an unreliable narrator. By immersing the viewer with the point of view of that character who tells the story from their perspective, the viewer believes whatever that character believes (or wants them to believe).

What’s important with twist endings is that the signs or seeds of the big twist are planted beforehand. This will undoubtedly be securitized upon repeat viewings and will give a different viewing experience which can make or break the twist.

In “The Usual Suspects,” Verbal Kint’s story is pieced together right there in the interrogator’s office from a police bulletin board. We see his eyes wandering around the room when he’s brought in, using his quick thinking to make up his account of the proceedings.

The fact that Kint is a con man who knows so much about the case when in fact he’s a small time player in the actual heist is among the more obvious telltale signs. No one has seen the mysterious Keyser Söze and lived to tell about it (until the very end), which makes Kint’s story all the more believable.

9. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Another interesting way of propelling a story forward with structure is with different sections. And there’s no better example than Stanley Kubrick’s epic masterpiece. Comprising of three distinct sections: 1) The Dawn of Man, 2) Jupiter Mission, and 3) Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite, through these sections, “2001: A Space Odyssey” explores our past, future, and the infinite possibilities.

Unlike hyperlink cinema which cuts back and forth between multiple storylines that are connected, “2001” lets each storyline run its course uninterrupted leading to the next section. While these sections may be different to each other in setting, time and storyline, they all add up to form part of the greater story or bigger picture.

The Dawn of Man explores mankind’s evolution and from ape to space travel at the beginning of the 21st century. Many people argue that the film consists of four sections and the famous jumpcut is a different section, even though there is no title to indicate such. The Dawn of Man primarily works on showing our evolution from ape to man, improvised weaponry to calculated space travel, both indicating that mankind in prehistoric times and in the 21st century is the dawn of man’s natural evolution.

The Jupiter Mission explores technology and artificial intelligence onboard a spacecraft called Discovery One that’s bound for Jupiter. Onboard are two humans and a supercomputer named HAL 9000. This section explores the relationship between humans and computers. Predicting the human races dependency on technology, HAL controls most of the ship’s operations. HAL has also developed human characteristics which end up endangering the crew and mission.

Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite explores extraterrestrial life and existentialism. As the Discovery One finally reaches Jupiter with its last survivor, the last section looks into the infinite and the possibilities of mankind’s next step in evolution.

All three sections progress naturally from one section to the other. Together they combine to tell a greater story and are linked by the film’s themes and the mysterious monolith that’s present at each important moment of mankind’s evolution.

“2001” takes a detached point of view with each section that forms the film’s overall structure. With an ambitious story like this, the audience never connects with any of the characters and is instead kept at a distance, as if they were watching a history programme.

8. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

While “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” uses different elements of storytelling such as psychological, science fiction, romance, drama, comedy and dream logic, they’re all combined with a nonlinear narrative.

The film follows the story of an estranged couple who decide to erase each other from their memories after a painful breakup, and then inadvertently fall for each other again as their past romance plays a hand in their current relationship. Primarily, the story takes the point of view of Jim Carrey’s character Joel and is set in his mind.

Feeling an instant connection with a new love interest at the beginning of the story, we soon find out that this isn’t a new love interest at all. Joel and Clementine were previously a couple. The beginning of the story where they meet for the first time is actually the end where they met yet again after having their memories erased.

The nonlinear narrative is perfect for exploring a character’s mindset, especially when they’re not sure what is going on. Charlie Kaufman’s complex script disorientates the viewer in the same way Joel is disoriented. There’s a chronological order for even the most complex of stories, and with the film there are three storylines: 1) takes place inside Joel’s head as his memories of Clementine are wiped, which are flashbacks, 2) takes place on the night of the procedure where the happenings of the employees who erase his memories fool around, which is the present and 3) takes place after his memories are wiped and he meets Clementine again, which are the “flash-forwards.”

All three storylines are told chronologically in a nonlinear structure, colliding in the end, making sense of the whole story.

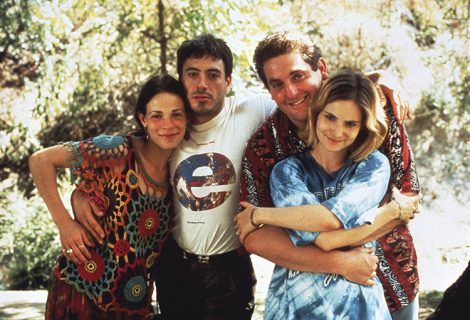

7. Short Cuts (1993)

Inspired by the short stories (and a poem) of Raymond Carver, Robert Altman’s “Short Cuts” tells the multiple stories of 22 characters who are loosely connected. Set in Los Angeles with themes of chance, luck, infidelity and death, “Short Cuts” boasts an impressive cast and 3-hour runtime.

Hyperlink cinema gives an all-seeing point of view which, in turn, gives the points of view of several different characters who are linked to the same themes and settings. For every action there is a reaction, for every cause there is an effect. While each character remains unaware of how another character’s actions may influence their own, the viewer is given a full peek at how they all interlock.

The location also plays an important role, where every character’s current location informs their current situation. In “Short Cuts,” it’s Los Angeles with the American dream and failure to achieve it. All the characters yearn for a better life and keep trying for it. Broken homes, broken dreams, a lack of identity and a hell of a lot of alcohol consumption are some of the similarities they all share.

There are no traditional main characters as they’re more or less given the same screen time and each character has their own arc. Cutting back and forth through these personal storylines that keep colliding until an inevitable climax that impacts all of their lives, “Short Cuts” is ambitious as they get.

6. Peppermint Candy (1999)

South Korea’s Lee Chong-dong’s second film starts with Yong-ho’s suicide and then keeps reversing to show us what led to him tragically take his life.

Repeatedly using the train as a visual metaphor that looks to be moving forward when everything else is moving backward, it not only guides the film’s reverse chronology but Yong-ho’s inability to move forward with his life with regards to his past coinciding nicely with his point of view.

As the story keeps moving further and further back, Yong-ho’s life coincides with South Korea’s history that more or less plays a part in his life. From his divorce and unhappy marriage to his various tenures career-wise, and the loss of his one true love, Yong-ho starts off as an idealistic young man who grows more bitter and cynical as life and his country’s circumstances have their way with him.

The two key moments of the story appear at the beginning of the film at Yong-ho’s student group’s reunion (which is the end), and at the end of the film during his youth as part of the same student group (which is the beginning). Everything in-between leads to his tragic suicide. These two key moments give the point of view of a character whose life didn’t turn out as he had hoped.

5. Pulp Fiction (1994)

“Pulp Fiction” could easily feature a number of entries on this list with its nonlinear narrative, different sections or chapters, interlocking storylines, and circular narrative.

The prologue and epilogue at the diner both follow the same story or event. Although chronological, they would appear somewhere in the middle of the film, and each time they appear they take a different point of view.

The prologue which opens the film takes the point of view of Pumpkin and Honey Bunny as they discuss their criminal career and decide to hold up the diner. With this scene, the viewer sees things from the couple’s point of view as the robbers. When the scene comes back again in the epilogue that closes the film, we see things from Vincent and Jules’ point of view as the customers.

Considering everything that’s happened with Jules and Vincent after the prologue, and what the viewer knows they are capable of, the epilogue takes a different meaning compared to when we first see it. Jules and Vincent are not your ordinary diner customers.

We expect a bloody finale because we know that Vincent will survive, since he dies in another scene and gets to take out Mia Wallace. But the genius of the script lies with another surprise. We know Jules wants out of his life of crime and has gained new perspective over his philosophizing. This new lease on life avoids the bloody finale where Pumpkin and Honey Bunny’s lives are spared and everyone gets to live (or die) another day.

As a circular narrative, “Pulp Fiction” works in pointing out how every action has a reaction and how different characters and events intertwine. It’s the perfect example of how one can use different forms of structure in a single film.

4. The Godfather: Part II (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola’s legendary and epic mafia crime film works both a sequel and prequel to “The Godfather.” It uses two different timelines; the sequel and main story follows Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone in 1958 as the new Don of his crime family. The prequel follows Robert De Niro’s Vito Corleone from 1901 to 1923 as he emigrates from Sicily in his childhood, to New York City where he founds his family enterprise.

There are many complexities in the two storylines that parallel and dissimulate each other. There are the two timelines and two characters, but they essentially exist in the same country and the same business.

In this, we’re given two different points of view from two similar but equally different characters who occupy the same position (father and son, nonetheless). Informed by different circumstances, situations and eras they morph each other if you also take into account the first Godfather film.

While Michael was born into the family business and comes into a position he eventually inherits, his fight is to preserve the family legacy. Vito, on the other hand, is a man who was born with nothing and his fight is to establish a legacy for himself and his family. It can be argued that Vito thrives and loves his position of power while Michael is a prisoner of it.

In the beginning of “The Godfather,” Michael was just like his father in the beginning of “Part 2”; idealistic young men who want to make something of themselves in the right way, the American dream way. In the end, they’re both “forced” to become ruthless men in the world of crime.

What makes “The Godfather: Part II” one of the best-structured films is its use of two different timelines which can be summed with the popular phrase: “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

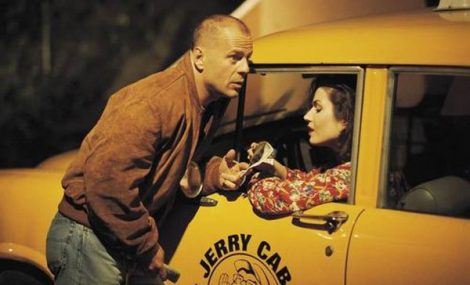

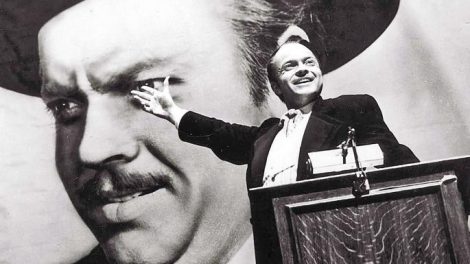

3. Citizen Kane (1941)

No other film has used the flashback motif as perfectly as Orson Welles’ stunning debut, a film that follows a reporter who’s tasked with finding the mysterious meaning of newspaper tycoon Charles Foster Kane’s dying words “Rosebud.”

From then on we’re given a portrait of the life and times, the rise, and fall of a complex and fascinating man. The big punchline is that it’s from the points of view of the people who were closest to him throughout the different stages of his life. The story is about Kane, but we never get the point of view of the man himself.

The flashbacks here are not used as some lazy form of exposition or character arc but in a natural and platonic way. Through the reporter, we see Kane as the world sees him; a powerful, rich and mysterious man no different than the way we see famous people today. Through the flashbacks, we see Kane the way his friends and colleagues see him while explaining how he became this powerful, rich and mysterious man.

Both the current storyline of the reporter’s search and the flashbacks are interesting enough on their own. But together they give the story a different and powerful perspective and raise the question how well do you truly know someone?

It’s apparent that Kane didn’t know himself as well. The way he contradicts himself and flip-flops through different ambitions, motivations and dreams, not quite sure what he wants or who he wants to be, makes using the detached flashbacks a necessary and perfect story structure.

2. Rashomon (1950)

No other film uses a point of view as well as Akira Kurosawa’s classic “Rashomon.” The film has influenced a wide number of stories throughout the years, where the point of view forms the crux of the narrative at large. With an unconventional structure, the story uses repetition as several characters recount their version of the same situation to a commoner in a gatehouse.

Examining the nature of truth and how it can impact justice, we’re given four different, self-serving accounts of the murder of a samurai and the rape of his wife. Using flashbacks for each account, the conclusions are the same but the means to it are different.

Each flashback fits perfectly with each character’s personality. The bandit’s story will, of course, paint him as innocent of any wrongdoing, while the wife’s story paints her as an honorable and innocent victim. Each account follows the narrative structure, having a beginning, middle and end.

By using repetition, the filmmakers make sure that each account of the story is different while making sense in its own right. Are most of these versions flat out lies or just mere communication problems? Even the eyewitness who would seem to have no cause to lie has his own reasons for giving his version. In the end, no one is as quite what they seem and we never find out the actual truth, like most things in life. The viewer is left to ponder and make up their own mind.

1. The Mirror (1975)

While David Lynch is known as the master of dream logic when it comes to cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky’s “The Mirror” is just as worthy. Loosely autobiographical with an unconventional structure, “The Mirror” unfolds as an organic flow of memories from a dying poet.

Combining scenes from childhood memories, dreams, thoughts, and newsreel footage that chronicle one man’s life throughout the 20th century, the film works as a stream of consciousness as it flashes back and forward without any indication, and the imagery changes from color, sepia and black-and-white unpredictably.

Set in three different timelines that are pre-war in 1935, wartime in the 1940s, and postwar in the late 1960s, time in the film is a mosaic of images. Like dreams themselves, the structure of the film is non-chronological, plotless and discontinuous. This proved confusing on its initial release and for first time viewers. But, like all of Tarkovsky’s films, it rewards patient and multiple viewings.

Focusing on the point of view of Alexei (who makes a brief appearance in the film), we see what he sees, hear what he hears, and feel what he feels. While some things remain opaque and unexplainable, the power of imagery evokes unspeakable understanding.

Allan Khumalo

You must be logged in to post a comment Login