- The Joy Division story has been told many times, yet it never stops seeming too bizarre to be true. Jon Savage, best known for his classic punk history, England’s Dreaming, was one of the band’s first chroniclers in the 1970s, but he tells the tale in a new way in his excellent new book This Searing Light, The Sun and Everything Else. It’s the ultimate oral history of one of rock’s most haunting legends, in the words of the band, their friends, enemies and witnesses. Savage goes deep into Joy Division’s earliest days: a gang of Manchester boys and their Bowie-besotted frontman Ian Curtis rise out of the urban interzone, only to get torn apart by death on the eve of their first visit to America. In this excerpt, this scruffy band – then calling itself Warsaw; they’d change to “Joy Division” soon after – gets together to play their first few gigs. Everything changes for them, and everyone else in Manchester, when a new band called the Sex Pistols come to town — everybody at the crowd goes away inspired to start their own group, talent be damned. —Rob Sheffield

Peter Hook (bassist, Joy Division): I went to work at the town hall. Because I didn’t feel I was cut out for it, I had to have myriad distractions while I was working, and basically it was reading. I used to read all the music papers from cover to cover, and I became one of the kids waiting for them to come in on a Wednesday morning. What happened with the Sex Pistols was that somehow the whole thing leapt out, because it was unusual after reading about heavy-metal bands for so long.

It was unusual, and it was a different culture. It was yobbish, which obviously appealed to me, being a yob. I cottoned on quickly to it. I remember going on holiday to Devon, three, four of us, in my Mark 10 Jag 420G, and we slept in the car for three weeks. We’d wake up in the morning and walk out somewhere looking for breakfast and trying to find somewhere where we could have a wash.

I spotted a Melody Maker and I bought it just to kill the time, and on the front page was the Sex Pistols, and it was the shot of Johnny Rotten fighting with the audience. I thought, “That looks interesting,” so I showed it to the lads. When I came back to work, I was going through the little adverts and the classifieds in the Evening News, just scanning them for anything of interest: “The Sex Pistols, 50p, Lesser Free Trade Hall.”

I phoned Bernard Sumner and Terry Mason and said we should go, which we did, and I’ve still got the ticket — 50p. I thought it was shite, it was just like a car crash, it was like…oh my God, I’d never seen anything like it in me life. I’d been to see most groups — Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin, loads and loads of bands — and I’d never seen anything as chaotic or as exciting and as rebellious as that. It was how I felt: You just wanted to trash everything. It sounded awful, and for some insane reason you had the blinding realization that you could do it.

Pete Shelley (frontman, Buzzcocks): I think there were about 42, 43 people. I’m not quite sure whether that’s counting me and Howard, or even the Sex Pistols. I was taking the tickets and the money in the box office, and so a succession of people would come up. Me and Howard really didn’t know anybody in Manchester. It wasn’t like we were part of a Manchester music scene, and we didn’t have many friends who lived there — it was just a big city to us. All these people who were walking through the door, it was a completely new experience for us seeing them, and for them seeing us as well. Because of the nature of the gig and because there weren’t all that many people there, it was a thing where people afterward were more likely to go over and have a chat with that person — “How are you? Because I remember seeing you at this” — just to break the ice. So it got people actually networking in a way which was impossible with the way that the music scene was, because there really wasn’t anywhere for people who were interested in music which wasn’t of the Yes variety or the pop of the day.

Bernard Sumner (guitarist, Joy Division): We eventually ended up at the famous Sex Pistols gig at the Free Trade Hall. It wasn’t that the Sex Pistols were musically brilliant and I thought, “Oooh, I really want to be like them.” It was the fact that they were not musically brilliant and could just about play together and it was a right racket. I thought they destroyed the myth of being a pop star, or of a musician being some kind of god that you had to worship. In fact, a friend who was with me said, “Jesus, you could play guitar as good as that.”

Previous to that, in the seventies, music was all based on virtuosity, Rick Wakeman playing a thousand-notes-a-second solo. A lot of that prog-rock and West Coast of America stuff was a bit soft and soppy: You were supposed to bow down. They were kind of gods, musicians: “Oh, he can play it so well, it’s amazing” — almost a jazz mentality. When they came on, the Sex Pistols trashed all that. It was like, you don’t need all the crap, all you need is three chords, right? Learn three chords, write a song, form a group, that’s it.

And that’s what we did, me and Hooky. I bought How to Play the Guitar, he bought How to Play the Bass. We went to my grandmother’s parlor, which was just across the Irwell. I remember we didn’t have any amps. She had an old gramophone from the Forties, and I took the needle out of it and wired two jack sockets on it. It sounded good, plugged into the gramophone — we didn’t have any money, that’s all we could do — and then we just started writing stuff together.

Peter Hook: So we formed a band that night. It’s easy — “Let’s form a group” — it’s all the rest that’s difficult. Bernard had a guitar that his mother had bought him. I can’t remember what position Terry took because he had the dubious honor of fulfilling every position with Joy Division, from singer right through to manager to lighting guy, roadie, guitarist, drummer. I went to Mazel’s on Piccadilly and walked in. “I want a bass guitar like that.” And they only had one: an SG copy for £35. Me mam lent me the money, had to pay her back. That was it then. Then we were a group.

Terry Mason (road manager, Joy Division): I dragged them there. At that point Hooky and Barney weren’t reading the music press — they weren’t listening to Peel. They’d settled down, they both had regular girlfriends and were quite happy with their world. All of a sudden the blinkers were off. Before that there was never any shortcut to being in a band; you really did have to put the hours in. Punk was more attitude than number of chords, and if you play it fast enough and loud enough, no one knows anyway.

Bernard Sumner: Terry was just one of the gang really. He’s quite eccentric. I think, to give him his due, it was him that may have turned us on to the Sex Pistols, ’cause he’d read in the NME about them fighting onstage. He said, “Let’s go and see this group. They beat each other up onstage, could be a laugh.”

Iain Gray (witness): Bowie and the Velvets spoke to me, as did Iggy Pop, but it didn’t inspire you to do anything. That was the cathartic moment, going to see the Sex Pistols. I can remember it like yesterday. I thought, “Christ, I could do this.” I do remember Ian being there. Hooky was there, and Barney. They reckon Mick Hucknall was there, but I didn’t see anybody that looked like Charlie Drake. I was in a band from Wythenshawe at the time called Ram. We went away thinking, “We could do this.” We didn’t, and I left that group.

Alan Hempsall: It was an early-starting gig: It was billed as a 7:30 start. It was the Free Trade Hall, so they had no option — it wasn’t a club venue. We’d gone into Virgin Records that day, and Virgin had printed off these photocopies of the very early NME piece about the fight at the Nashville gig: They described Johnny Rotten as a dementoid and the group as beating up their audience. We had to go and see that for 50 pence, and then we just went along that evening, found out what time they were on, and although I was 15, I was home for about half past 10, 11 o’clock.

They were supported by a hippie band called Solstice, who did a cover of “Nantucket Sleighride” by Mountain, so this was lulling us into a false sense of security. Then the Sex Pistols came on, and they immediately looked weirder than the bands of the day. I had a friend of mine sat next to me who, obviously with the name Sex Pistols, just blurted out, “Oooh, you’re not very sexy, are you?” And Johnny Rotten immediately fixed him with the glare and said, “Why? Do you want some sex?” My friend responded, “Oh, didn’t expect that for 50 pence.”

They then launched into this set, and they were very proficient musicians. Don’t be fooled: The Sex Pistols could play, and play very well. There were probably about 45 people in the audience, 50 tops: a mixture of Bowie clones and hippies. I identified with it straight away. We were up at the front when the encore came on, and we chatted to John Rotten for a couple of minutes when he was getting ready to gear the band up for one last hurrah.

Paul Morley (writer, New Musical Express): I just think of them as being weird music lovers that were crawling out of their bedroom where they spent all their time, because they would be social retards, and the only way they could ever get on with anybody else is to be in a pop group. So we found ourselves, and the funny thing about Manchester, of course, is there wasn’t really any center to Manchester, everybody came from somewhere else: Stockport, Chorley, Oldham, Macclesfield, Salford. Everybody came into what was almost like a little village.

I do remember going into the first one, when there really wasn’t very many people there at all, and it was an incredible kick. Suddenly it was with us, it was in our surroundings, and every-body looked really odd. It’s only now when you see the footage that of course they weren’t: They looked quite ordinary, their haircuts weren’t mad, they were just slightly shorter, certainly in that first one. We were just semi-hippies still and hadn’t quite yet made the move into a new world.

When the Sex Pistols turned up, that’s when it went a little bit bizarre. They were queasy in the way they looked: not so much the four members of the group but their entourage, hanging off the side of the stage, this weird combination of bondage get-up dwarves out of some weird Thirties horror movie, Freaks. It just seemed so exotic.

The Pistols themselves didn’t look that far removed from the Faces, to be honest. The way they played was different: It was more theatrical and it was more knowing about its theatrical nature, and that seemed somehow far removed from rock. It was something else. It did seem more surreal and more weird, even though the patterns they were playing and the chords they were playing and the songs they were playing were quite traditional. It was trad, but it had this weird avant-garde edge.

I went on my own. It was like going to see Faust or Beefheart, because you could hear rumours coming up from the south that made you think, “It’s like the Stooges, something really strange is going to happen here.” Strange unformed half-boys all gathering in this peculiar little theater, but you wouldn’t talk to anybody, you’d kind of look and get a sense. The support were Solstice, the hippie rock group from Bolton that played covers of Mountain, so you didn’t quite get the sense it was a revolution. That happened six weeks later.

Tony Wilson (presenter, Granada Television; co-founder of Factory Records): The first night, I didn’t know what the fuck was going on, until they played “Stepping Stone.” As soon as they did that, it was clear that they were deeply and remarkably and fabulously exciting. I went back to Granada and said, “We must put them on the show,” and the researcher, Malcolm Clark, was asked to check them out with me, and we went to Walthamstow Assembly Hall, and that again was a completely non-attended gig: maybe 80 people, of whom 40 were in a large, single-line semicircle, just out of gobbing range.

Peter Hook: After the Sex Pistols, there were so few people there that you just talked to them, because if something awful had happened, you’d talk to the person next to you, wouldn’t you? If you watched a crash, you’d say, “Oh, Jesus, that was bad, wasn’t it?” Normally you wouldn’t ever talk to people, but because you’d witnessed something awful, which was the Sex Pistols, you’d talk to the people ’round you. You just got caught up in the excitement of it.

Richard Boon: Manchester seemed like a vacant set. Some kind of neutron bomb had been dropped, leaving derelict buildings. There was no centrer of gravity; it was the cradle of capitalism and was rapidly becoming its grave. There was no scene, there were no bands. I did music listings for a fortnightly called New Manchester Review, a very slim volume. To fill the music listings you had to include places like Stalybridge, for heaven’s sake. There was really nothing happening.

After the beat boom, when Manchester had a fantastic number of bands, as did Liverpool, a couple of things happened. The Beatles moved to London, shut down Liverpool effectively. The police shut down Manchester. There were hardly any places to go: There were the universities, the polytechnics, but they were not necessarily open to people who weren’t students back then, and there was the debris left over from prog rock doing the Free Trade Hall.

It was like some disaster area, and there was hardly anywhere to go. There was no one to see. Something had happened. All the bands that would have filled medium-sized halls had gone, and then you just had really crap imitations and the few pubs that put anything on. It was a challenge because Manchester had a spirit which was in the place and in the people, but hadn’t been energized.

Pete Shelley: By the time we did the second show on July 20th, we had managed to get a bass player and a drummer. In fact, I was introduced in the first Sex Pistols gig by Malcolm McLaren to this guy who’d just been standing outside waiting quite innocently to meet somebody else, and Malcolm said, “Are you a bass player?” And this guy said, “Yes.” And Malcolm said, ‘Well, they’re inside,’ and he came up to the box-office window and said, “Here’s your new bass player,” and there was Steve Diggle looking quite bemused.

So I said, “Well, Howard’s upstairs, so you’d better see him,” and by the time we found out that he was there to meet somebody else, we said, “Well, the Sex Pistols are just about to play, why not watch it?” This is the kind of ballpark of what we were trying to do, and the next day he came for a rehearsal. Then we had a 16-year-old drummer called John Maher, who’d only had a drum kit for about four or five weeks before he joined the band. Me and Howard had been writing songs since late 1975, so we had a few songs that we could play and so we managed to do a set.

Slaughter and the Dogs had bent Malcolm’s ear and said how they were a huge band and that they thought they would pull more people than Buzzcocks ever would. And so there were more people, but they tended to be either people who were Slaughter and the Dogs fans or other people who’d been at the first gig or who’d heard about it through their mates and actually thought, “Oh, let’s go and see it.” And by then the news of the Sex Pistols was growing, so they started to attract more people.

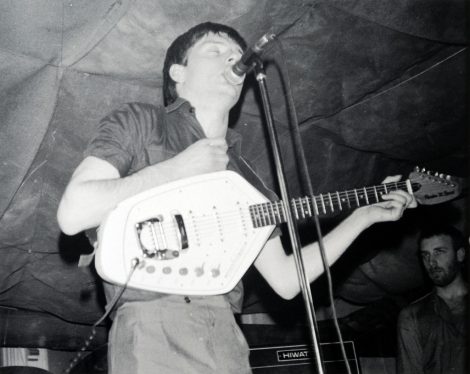

We went on and did our half an hour, and then finished the set by leaping off into the audience, because we thought that was a different way of doing it, since it was all about trying new things and messing with the preconceived perceptions of what a gig should be. In rehearsal I was playing the sawn-in-half Starway guitar, but it wasn’t actually sawn in half: one day in a rehearsal I was doing wild guitar, the chaotic random bit, and took the guitar off and threw it on the floor, and it split, and we thought, “Well, we could easily do another one of those.” So I bought an Audition Guitar from Woolworths which was about £20. I thought, “Well, I can destroy that, it’s worth doing it,” and so me and Howard decided that at the end of the last number we would both attack the guitar, and he was there ripping off the strings, so it was a chaotic end. We smashed the guitar, and it all looked good.

The Sex Pistols had actually gotten a lot better. I think it was that night the first time I heard them play “Anarchy in the U.K.,” and from the moment it started it was like a frisson of hearing something which is really a landmark. It was like opening the door and a herd of elephants rushing in.

Paul Morley: When I went a few weeks later, somehow I had turned into a hooligan, and I almost got thrown out for throwing peanuts at Wayne Barrett, the lead singer with Slaughter and the Dogs — who already seemed fake. Six weeks after the Pistols arrived, we were making decisions about what was and wasn’t fake and bandwagon-jumpers, and Slaughter and the Dogs seemed like bandwagon-jumpers. Whereas Buzzcocks, who were bottom of the bill, they already seemed to be the real thing, and they were local.

Pete Shelley: After the second one, there were people who you’d seen from the first one, and of course they’d come up and start talking to you, and there were lots of people interested in starting bands or starting a fanzine. Because punk was very inclusive, it didn’t say, “We can do it, you can’t, and that’s the way it’s going to stay,” which is what most forms of art were about. With punk, it was saying, “Well, have a go, you know, why don’t you do it?”

Because it was also something which had so much humor in it as well. People had more fun thinking about all the outrageous things that you could do than was perhaps ever attempted in the end. Most of the time you were just thinking about all the crazy things that you could get up to, if you allowed yourself this freedom.

Peter Hook: We went to see the second Sex Pistols gig, when the Buzzcocks supported them, and we were in it then, we were actually in the scene. I mean, we got pushed out a bit later because we were just too working class for Howard Devoto and all that lot. I think they thought we were yobs, which we were. I think it was just ’cause of our friends and the way we’d been brought up and the place we’d been brought up in. They’d all sort of escaped to art college, and so they had this freedom, if you like, whereas we hadn’t found that freedom yet.

But it was a great scene. It was like going to the Ranch in the early days with the punks, there were so few of them. Me and Barney didn’t know them, but they all seemed to know each other, yet we still used to go.

Pete Shelley: We heard that there was this bar called the Ranch Bar, which was a small bar in the basement of this building on Dale Street, and it was next door to Foo Foo’s Palace. Foo Foo was a female impersonator, very much along the lines of Lily Savage, a very acerbic wit. It was basically an underage drinking den: If you looked over 15, you could get in and get a drink. The drink of choice was Carlsberg Special Brew, a bottle through a straw, so that’s what everybody used to drink, and you used to have about two or three of those and it made for a good night.

In August of ’76, after we played at the Lesser Free Trade Hall with the Sex Pistols, we went to see Foo Foo at his massage parlor and sauna. He came in for this meeting and he was wearing a towel around his shoulder, so it was very Seventies gangster type, more like a scene out of The Sweeneythan anything else me and Howard were used to. We said, “We’d like to put on a gig at your club.” He listened to us and thought we were a bit weird, but said yes, it was a good idea.

So in August we had a gig, which was a draw for all the people who normally go to the Ranch Bar and all the new people who’d started hearing about the Buzzcocks and wanted to hear more about the music. I think we got through a few songs before Foo Foo came in in full regalia and said, “Better stop that infernal racket.”

The Ranch was full of Bowie and Roxy kids who probably couldn’t get into Pips. I think it was just Fridays and Saturdays at the beginning, but then Sundays became a good night as well, and people used to meet up. I remember the first time I saw the people who then became the Fall. They were in there, and I’d seen them in the bar. It was always a small place and it held about, I don’t know…if we had 50 people it would probably feel very crowded and so it was just about the right size. It was the kind of place which didn’t mind the way you looked.

A lot of bars when you tried to get in, if you were anything remotely unconventional they’d have a fit and they wouldn’t let you through the door. Because it was a drag act we were under — a club in a basement — there was a more liberal door policy, and therefore people could come in and listen to music which nobody else would entertain.

Tony Wilson: Then we put the Sex Pistols on So It Goes. We decided to make a virtue out of our last show, with three unsigned bands. They behaved pretty badly. They had a row with Clive James. They had drunk quite a bit. They were meant to do three and a half minutes — they agreed that and rehearsed it — and there was five minutes left, and they just kept playing for seven minutes and kicked their equipment apart. Two days later, the director edited it down to three and a half minutes. The next day, I was in trouble at Granada — there was bad feeling.

Pete Shelley: On the surface you wouldn’t think that a jean-shirt-clad TV presenter would be the one who would take an interest in what was going on in punk. He was the man on the telly, he presented the local news program on Granada. It seemed really strange him turning up at punk gigs, but in a way it was exciting because they had somebody who had at least a passing association with what goes on on the TV, and then when he started doing his program So It Goes, he invited the Sex Pistols up to play.

Paul Morley: There was a strange gap after the Sex Pistols gig in July. There was a pause as everybody got themselves together. I think Buzzcocks did a gig on Deansgate with Chelsea. I remember having a drink with Billy Idol and Tony James and Steve Diggle. It all seemed very exciting because suddenly I, the lonely weirdo, was speaking to Howard Devoto on the phone. I asked him his five favorite words, and he said, “I like eating ice cream,” because it turned out he was eating ice cream at that moment.

At these places the guys looked exactly like me in a way — especially after I’d had my hair cut short — and they were wearing their granddad’s clothes, as if this was our fashion statement because it was all we could muster. But there was this gap while people like Warsaw wandered off to work out how to respond, and suddenly they could, they could respond because they’d seen it, certainly with Buzzcocks as well: A bunch of local people, about their age, liked the same kind of weird music they did and had formed this band that were really good.

Richard Boon (manager, Buzzcocks): I met Ian Curtis on November 10th, 1976, at the Electric Circus, where Buzzcocks, in the tradition of doing it for yourself, had hired the Electric Circus and brought Chelsea up from London. I was doing the door. Ian came in talking about having a rubbish time at the Mont-de-Marsan Festival, which had been hyped in the summer as being some legendary French thing, which he found ultimately disappointing, but he was obviously coming from the same kind of idiot enthusiasm that we were sharing.

Pete Shelley: The Electric Circus started off as a heavy-metal place. It was a fair-size hall, it had a proper stage at one end. It was painted black, it was very dark — there was a bar at the top, on one side and towards the back. As punk started, they realized that they could get more people in by catering to the punk audience, and over time they got to be the primary venue for anything to do with punk or New Wave in Manchester. It was in a place called Collyhurst, which was a run-down council estate. It took you about 40 minutes to walk from Manchester city center, but you needed a bit of an escort, at least a few of you to frighten away the dogs which were prowling.

Richard Boon: There were very few venues. There was the Electric Circus, which was like at the end of a bomb site up Oldham Street. Then there was Pips, which was a disco, post-Bowie, post- confusion, post-glam, post-apocalypse. There was the Band on the Wall, which was trad jazz mainly but had its off nights; you could get it cheap if you could persuade the booker to let you have it on a Monday. You had to find these places that were left over, such as the Holdsworth Hall, which once upon a time had classical music and stuff; it was idle.

Peter Hook: The first Sex Pistols gig at the Electric Circus was really good. We had all the publicity for the “Anarchy” tour. I had a poster of that for ages, and then my mum threw it out. Then there was Bill Grundy, and then they played it again because they had all the shows cancelled. That was just a riot, there was so many football fans and lunatics waiting in the queue outside, throwing bottles from the top of the flats. It was really heavy, a horrible night.

Richard Boon: The move toward recording Spiral Scratch came out of the fact that we’d had to put on our own gigs, but when the “Anarchy” tour swept through, there was a real sense that the original punk impetus was dying out. It was becoming clichéd and tabloid, which we really didn’t feel part of, but we wanted to document what we’d been doing. A record had to be made just for that moment, and with a little basic research and some fund-raising from friends and Peter’s family, we pressed a thousand copies, not really knowing what we were going to do with them.

John Webster, who was managing the Virgin Records store at 9 Lever Street, said he’d take a couple of hundred and phoned some of his regional colleagues: Obviously Virgin had a central buying policy — they would have taken more persuasion. Geoff Travis at Rough Trade rang up, and suddenly we’d contributed to the unleashing of potential that we saw as the core of the early punk movement. We kept re-pressing until we reached about 16,000.

Martin Hannett (producer and director, Factory Records): I went to the second Free Trade Hall gig, in July. I thought the Pistols were very competent, tight rhythm section. I enjoyed it. I thought the Buzzcocks were great too. I was involved with Slaughter and the Dogs, who I thought were barking up the wrong tree, ’cause they were doing glam stuff. I was really looking forward to the first Pistols record, and when I got it home, I thought, “Oh, dear, 180 overdubbed rhythm guitars. It isn’t the end of the universe as we know it, it’s just another record.”

The first punk record I produced was the Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch. Richard came in and said, “We’ve done some gigs. We’ve been in the papers. What do we do next?” So I said, “You make a record next.” Mr. McNeish, Pete’s dad, came up with the money, and we went into Indigo, 16-track. Again, I was trying to do things, and the engineer was turning them off when I looked round. “You don’t put that kind of echo on a snare drum!” It sounds like it was done on a four-track.

It was never finished. I would have loved to have whipped it away and remixed it, but the engineer erased the master because he thought it was such rubbish. It sounds like a monitor mix these days. The guitars were really trebly. I just compressed them and added more treble. I loved guitars. That’s what they sounded like, it’s a document.

Paul Morley: At the end of ’76, I guess the Electric Circus had the Pistols come twice, with the Clash, and Buzzcocks played with that, so our local boys were actually right in there, which was incredibly exciting. I don’t think I really came across Warsaw until they were Warsaw, and then the strange clubs that started to open up in peculiar cellars and strip clubs and odd parts of the university, they would just be there and they’d be playing, and that’s when I would start to notice them.

Iain Gray: I was trying to put another group together and I advertised in the old Virgin Records for a high-energy singer. Somebody had written on it: “Must be able to withstand 10,000 volts” — Manchester wit. Ian Curtis was the only one who answered. We met up in a pub in Sale called the Vine Inn. Ian turns up with a jacket with “hate” on the back, which was a pretty dangerous thing to do in 1976 Manchester. He walks into the pub in a donkey jacket. I’d already been getting daggers from the locals, like, “What the hell’s this? What’s he?”

Then Ian walked in, and he was a really sweet, nice person. You’d look at him and you’d think, “Christ, quite a frightening-looking guy”: leather pants, this combat jacket with “hate” on the back — a bit like De Niro in Taxi Driver, because I know he was really into that film. I remember talking that night, and he seemed a lot older and more mature. I was 18 at the time, and Ian would have been about 20, 21. And I was going like, “The punk ideals, Ian. Being married —boring.” And he went, “Oh, I’m married,” and he shows me his wedding ring.

I’d go round to where Ian and Debbie lived with his gran, Stamford Street, in Hulme. Because it was around Christmas, his gran had put all these balloons up, two round ones and a long one in the middle, so it was phallic shapes all round. His gran was totally naive to it, but Ian was laughing. He was a really nice, sweet guy — flowers for Debbie, chocolate. I’ve never met a couple before or since who were so happy. I envied it.

Ian was the picture-postcard happy guy. He didn’t have kids then, but it was roses ’round the door. He’d be there smoking his Marlboros — he smoked a lot. He drank Colt 45, but he didn’t really drink much. He’d sit with Debbie, and they’d watch telly together at his gran’s and have their tea together on their knees. He was a young civil servant; he was upper working class, which existed then. It’s pre-Thatcher, but he was a Tory: He had aspirations, he was motivated. He had more of a fire in his belly that he was going to do it.

Debbie would stay in. We’d always go to the Electric Circus or early Buzzcocks. We saw the Damned in 1976 at the Electric Circus, and both nights of the “Anarchy” tour. We just swapped records at the time. He was well into Iggy Pop, like I was, but he also had a deep love of heavy dub, Jamaican reggae: Lee Perry stuff, U-Roy, I-Roy. He was just like me: He talked about going to that Sex Pistols gig and thinking, “I’ve got to do this.” He’d gone to the French punk festival with Debbie. I’d never even realized that was on at the time.

We decided we’d go to London about two weeks after we’d met, just to see what was happening there. We did the King’s Road: We went into Sex, Malcolm McLaren’s shop, and we went into the Roebuck. Didn’t see any of the Pistols, although we were hoping we’d bump into them. We bumped into Gene October, who played with Chelsea, and we were going to get a gig for them in Manchester and we’d play with them.

I remember we spoke to Don Letts. He stood out with his dreadlocks — he looked pretty cool at the time. He says, “I know a band” — which must have been the Clash — “but they’re not ready yet,” because we said we could get gigs for London bands in Manchester, i.e., we could support them. Ian just went up to Don Letts and went, “Do you know any bands in London? Because you look dead cool.” Ian would initiate conversation with people; I was a lot shyer. Ian was shy but could do the chat as well.

We hadn’t actually rehearsed at this point. There would be sheds in people’s gardens and pubs. I was the guitarist and Ian was the singer, with his little briefcase full of lots and lots and lots of lyrics. After about a month I started looking at them, and I remember “Day of the Lords,” “Leaders of Men” and a rough draft of “Candidate.” At the time — it was 1976 —he was really into these punk Nazi fiction books by Sven Hassel, about German tank commanders, and his favorite one was Wheels of Terror. “Leaders of Men” just made me laugh because it was straight out of the pages of Sven Hassel. You wouldn’t admit to reading that by 1979-80, we were all very left wing by then.

We were rehearsing, me on the guitar, and Ian did the very first dead-fly dance. I’m playing this crap song, really going for it, and Ian’s giving it this — like his head going back and eyes going up in his head. As far I knew then, he wasn’t suffering from epilepsy; if he did, he kept it very well-hidden. I never saw any indication, but he would have these kind of void moments, and when he did that there was something of the night about him. It was very strange because he was such a sweet, warm, generous person.

Around that time we met a bass player. We were just jamming at the time. We played in the Great Western pub in Moss Side, where we rehearsed. I’d phoned up and said, “Could we play there?” We set up in this pub, and all these locals in a really rough working-class pub are really staring at us. Ian’s there with his jacket and screaming away, and they chucked us out — “Get out!” Ian hadn’t really developed his singing voice. You never heard him singing, he was more kind of grunting, hunched over his lyrics.

We got through Christmas time. We could never get a drummer. We toyed with a few names, and he picked Warsaw, because that Bowie album was a big influential record with Ian at the time. We had great ideals but it never really took off, so around about February it just fizzled out.

Bernard Sumner: We got so far down the line, and we thought, “Right, we need a drummer now and a singer, obviously.” We didn’t know where we were going to rehearse, couldn’t put a drummer in my gran’s. And we advertised for a drummer and singer in Virgin Records, which was then in Piccadilly, so that was the punk thing. We were going out to loads of punk gigs by then: There was the Ranch, and there was a bit of a scene forming — you’d get to know people on that scene.

Unfortunately, I was the only one with a telephone, so I put my number down, and we ended up with a load of cranks. Me and Terry went in his Vauxhall Viva over to Didsbury, met this guy who was a total hippie, and we were punks, right? We went for a pint with this guy before, and we went to his flat. I remember him sitting down, and he didn’t have chairs, he had a cushion, sat cross-legged, and we had to sit on cushions opposite him. We were glancing at each other, going, “What’s going on here? What’s going on?”

Terry Mason: Barney already had a guitar and an amp, so he was pretty much set up. Hooky went off and bought a bass guitar, which was a shame because I’d thought about that one myself because I’m taller — bass guitars go for the taller man. Then I was going to get a guitar, and it was just a matter of getting the money together to do that. In the end, it was once we’d met up with Ian and he decided that he was going to be in the band that I actually got a guitar.

We tried within our circles for a singer, one of them being a guy called Danny Lee, who was a friend of Hooky’s. Danny was fantastic, he looked more like Billy Idol than Billy Idol ever has done — he had the lip going, the sneer — and he thought he was ready to sing, but never did. So then we decided that we’d have to talk to other people, which was new to us — we were quiet and shy people — so we put up the advert in Virgin and we had a few responses.

One in particular was this complete madman. He looked like how Mick Hucknall looks now. He had long red hair in a ponytail, he had a bit of a Catweazle growing on his chin, and he appeared to be wearing a cushion cover as a jumper, as if he’d just cut holes in it to put his arms and his head through. We’re there in this madman’s flat, and he then pulls out a three-string balalaika and starts strumming it and singing to us, and we basically ran out of there. After that we thought, “God, this is going to be difficult,” but fortunately Ian responded to the ad.

Bernard Sumner: I first met Ian at a gig at the Electric Circus. It might have been the “Anarchy” tour — it might have been the Clash. Ian was with another lad called Iain, and they both had donkey jackets, and Ian had “hate” written on the back of his. I remember liking him. He seemed pretty nice, but we didn’t talk to him that much. I just remembered him. About a month later, when we decided to try and find a singer, we put an advertisement in Virgin Records in Manchester, which was the way that all groups formed during the punk era.

We put an advertisement in there, and I got loads of headcases ringing me up. Complete maniacs. Then Ian rang up, and I said, “Weren’t you the one I met at that gig, that Clash gig? With the other Iain?” — “That’s me,” he said. So I said, “Right, OK, you can be the singer then.” We didn’t even audition him. We asked what sort of music he liked, and it was the same kind of music as us, so we gave him the job. Ian and Debbie were staying at Ian’s mother’s at that stage, near Ayres Road in Moss Side, and me and Hooky went over to see him in person and gave him the job then.

Peter Hook: The first time I met Ian was on the stairs in the Electric Circus, ’cause there was a kid in front, he had “hate” on his back in white letters in masking tape, and he used to peel the masking tape off when he went to work in the morning. Let’s hope he remembered. He turned ’round, and it was Ian, and we went, “Oh, bloody hell, you’ve got ‘hate’ on your back.” It was a bit extreme, we thought, but I suppose we were all at it. We’d seen him at all the gigs, and it was that childish enthusiasm.

He formed his band with his mate, but there was some unwritten law about how punk bands didn’t have two guitarists, you just had to have one. He had a singer and a guitarist, we had a guitarist and a bass player, so he couldn’t join. We had to wait until it changed, and that meant that Bernard and I were trying to get a singer. I can’t remember how wholeheartedly we were doing it, but everything seems to click into place once Ian joined us and we became the three of us. We met him at a gig, and Ian had lost his guitarist, and then we joined up and he became our singer.

Terry Mason: I think we were just glad at that point that he wasn’t wearing a cushion cover. We vaguely knew him, more on the grunting terms that young men do. The punk situation in Manchester was you basically knew most of the people who went to every gig by sight, you didn’t know what their name was, but you’d [mumbles]. He seemed OK. We got talking to him, he came out with his books of lyrics, and he had a lot of index cards with songs or bits of songs on, and he actually owned equipment: a couple of column speakers and a tiny amp.

It was obvious that this guy was serious. He was prepared for it and he didn’t scare us, so we decided to see if we’d like him. So Ian’s audition as such was we invited him to come out with us one Sunday afternoon, and we went to Ashworth Valley, in Rochdale. Basically, we spent a couple of hours just acting like kids, throwing bits of wood into streams and jumping over them. On reflection, it wasn’t a bad audition technique. It worked. I’m not sure what Ian thought of it when he went home and told Debbie what he’d been up to.

Ian went and saw Iain Gray and told him that he wasn’t with his band anymore, and just to rub salt in it, would he mind selling his amp and speakers to me? So I bought Iain Gray’s equipment, but I just can’t play guitar. Every time I try, I just can’t do it. The problem was, there was already a stagger in the competence. Barney’d had his guitar for a couple of years — he could pick out a few chords. Hooky had got his bass guitar and was learning. By the time I got ’round to that, I was, what, two months behind Hooky, but maybe two years behind Barney.

We then had the problem of finding a drummer, and real drummers are very hard to find. We went through a number of people. Later on, I traded in the guitar and amp and got a drum kit, but yet again I was then so far behind everyone that it was obvious it was impossible.

Peter Hook: Ian was much better educated for things like Can, Kraftwerk, Velvet Underground. I was a big fan of John Cale, because a kid I used to work with in the canteen at the Manchester Ship Canal Company was a mad John Cale fan, and he gave me all his LPs. It was Ian that introduced us to Iggy and things like that, because Bernard and I were listening to pop reggae, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple. Ian didn’t push it on you — he wasn’t pushy with us at all — and he was just great to be with, he completed your education.

Bernard Sumner: He brought a direction. Ian was into the extremities of life. He wanted to make extreme music, and he wanted to be totally extreme onstage, no half measures. If we were writing a song, he would say, “Let’s make it more manic! It’s too straight — let’s make it more manic!”

Tony Wilson: It was Debbie who introduced Ian to Iggy. I think it was the lads told me this. Debbie is the Iggy Pop fan. Ian met and fell in love with Debbie, and she started playing him her Iggy albums. The whole point of music is the coming together of influences, so in that moment you’ve got something as important as Ibiza. Because Ian took Iggy to the band.

Kevin Cummins (photographer): When we went to see Iggy in March 1977 at the Apollo, with Bowie on keyboards, I think that’s equally as important as the Sex Pistols at the Lesser Free Trade Hall. It really galvanized a lot of people. Iggy was mesmerizing on that tour — he was astonishing. I’d never seen anything like it.

Bernard Sumner: We rehearsed at a pub in Weaste called the Swan. You know like you had the Freemasons, you also had the Buffaloes. I think they’ve got a secret sign. We rehearsed in their meeting room above the pub, and it used to be all like weird chests under the seats. When we pulled them out and opened them up there’s like buffalo skins. They’re a little-known secret sect. It’s all based on Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings. When the Buffaloes weren’t having meetings, we rehearsed there, which was great, until the landlord threw us out.

What was going on then, I guess it was like when you first have sex, if you’re a complete virgin, and the first time you do it you’re completely hopeless at it, you get it all wrong. That’s what happened then, in that period. The first songs that we started playing, maybe you’ve heard some stuff, but there was a previous set of songs before that that were absolutely bloody awful. Music’s like anything else: You have to educate yourself, or be educated by it, until you’re good at it. Those were the days of our education.

The first set of material we wrote was just us aping punk, completely aping it and doing it really badly. We were the musical equivalent of nine-year-old kids, so we wrote about seven songs. We got pally with the Buzzcocks, and they were really helpful to us. They helped us get gigs. Pete Shelley sent Richard Boon down to see us, and he came and we were playing, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, fuck off, fuck off, yeah, yeah, yeah, bollocks, bollocks” — these really dreadful, dreadful songs.

He said, “Well, I’ll give you the gig, but you need to write a new set of songs.” We thought, “Yeah, yeah, they’re crap really,” so we wrote a fresh set of songs for the gig. I think it was at the Electric Circus, supporting the Buzzcocks. We wrote six songs which were much better, but we still weren’t there yet. They were better than the first lot, and we wrote them in about six weeks. Some of them, I think, ended up on Unknown Pleasures, maybe two.

Pete Shelley: We had a meeting with them one Friday evening because they said, “We’d like to start a band up, we need some help.” Punk was an inclusive thing, and we needed all the similar-minded people that we could have to make it a growing concern. And so this Friday evening we’d arranged to meet at this pub in Frederick Road, in Salford. It was just basically having a drink and talking about the things which they wanted to do, and we were trying to think of ways that those things could be accomplished.

I remember going to Bernard’s house, and he had these effects, but they weren’t effects pedals because they actually plugged directly into the guitar, so it was quirky even for those days. And it was just basically encouragement, the way that things probably started in many schools and things. I mean, there was a sixth-form feel in a way, people just exchanging ideas about what could be done, and how.

Richard Boon: They were in a constant process of forming. We used to visit them in the rehearsal room near the bus depot in Weaste and drink with them afterward, and they were just trying to get a handle on what they wanted to do. They just wanted to be in a band, which is no mean ambition.

Ian was possessed by burning youth. I wouldn’t go as far as to say he was anything like Arthur Rimbaud, but he was enthused primarily by the Stooges and the Velvets and his own sense of alienation. He was obviously trying to work something out and he could be as laddish and as loutish as the rest of them, but you always sensed he’s making an effort to be a lad — he’s really a little more withdrawn, a little more thoughtful, which just made him charismatic, but he was no saint.

Bernard Sumner: Ian used to have this really thick hair, and he used to go to this dodgy barber’s and ask the barber to cut his hair like a Roman emperor. We used to be quite into the Romans. He used to read a lot of Nietzsche. I don’t know — I never read it, I just thought they were beautiful uniforms, and beautiful architecture. So aesthetically I was always attracted to classicism. Ian liked it through Nietzsche.

Peter Hook: We supported the Buzzcocks at the Electric Circus. That was the first one. We didn’t have a name, and Richard Boon wanted to advertise us. And we couldn’t decide, and in the end he said, “Well, what about Stiff Kittens?” Pete Shelley came up with it, and we said, “Oh, no, we don’t like that.” He said, “Oh, all right then,” and then put it on the posters. On the night, we had to announce that we were called Warsaw, and not Stiff Kittens.

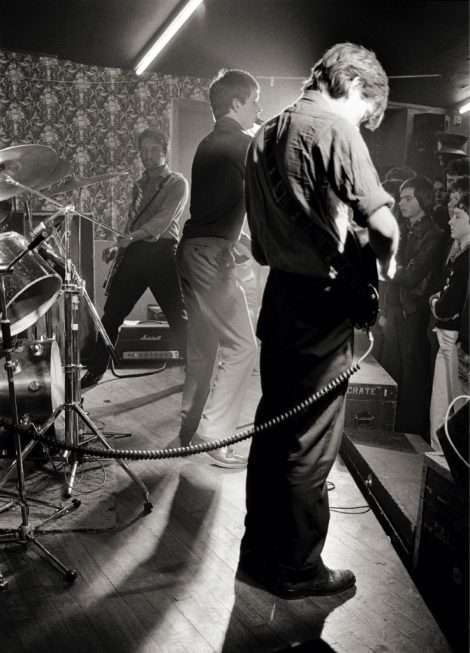

I remember being absolutely terrified. One minute I went onstage, and I remember that and I don’t remember anything else. I remember coming offstage and it was like, “Uhhhhh, absolutely terrifying.” I’ve seen a picture of the first gig. Me and Terry had decided to dress up as tank commanders, and we’d bought a load of military German tank commanders’ outfits. But that’s the great thing about being in a group: You have a history of every ridiculous outfit you’ve ever worn, and every ridiculous haircut, and every ridiculous thing you’ve ever said.

Terry Mason: We thought we were doing the standard Manchester punk progression. You would do gigs with Buzzcocks in Manchester, and then go off and do gigs with them elsewhere, as had happened with both the Fall and the Worst, but we seemed to stumble on that. We did the first gig with them, and then we heard nothing more. We then got a string of gigs basically through Music Force: They tracked us down, and we ended up doing some support slots at Rafters.

The decision was that the band didn’t like Stiff Kittens, which was the working title that Pete Shelley had given us. I thought it was a pretty cute name. Stiff Kittens as a punk band — it’s a fantastic name: a box full of little kitties with their paws up in the air — how more punk could you be? But the band didn’t like it, so it became Warsaw, mainly after the Bowie track “Warszawa,” because we used to go on to that at early gigs.

Iain Gray: When they supported Penetration, Ian did a very mild version of the full Ian moment. They were good, not great, then. Ian always had great fashion sense. He had these really smart Tonik pants, and he used to wear this RAF greatcoat all the time — it was utilitarian, Berlin 1935, that type of style. You had Barney with the mustache and Hooky dressed like a gay dancer, one of the Village People: It was quite odd at the time, his peaked cap, because he used to wear it at Pips. He had a leather collar with studs on, so it was a bit of a mish-mash.

Kevin Cummins: They weren’t very good, but it didn’t really matter because it was just so zeitgeisty. I think that was what we felt with nearly every band. We weren’t that critical, we were just pleased that people were getting up and doing something. I shot about six or seven frames, but the negs have long since disappeared. I remember it had energy, but everything had energy then. You’d see Chelsea or the Cortinas or Eater, and they all had energy. The songs were quite interchangeable. I think that was the case with Warsaw for a while.

I always used to shoot the support band, even just three or four frames. I felt I was in the middle of documenting something that could be important. Not necessarily that band, but everything. I had a feeling that I was going to do something with it, so I wanted to be as complete as possible. I was really into glam, Bowie and Roxy Music. I didn’t dress like a punk. I felt I was observing something. I did feel a part of it; it was very easy to feel a part of that group, no one was excluded. London was very cliquey, but Manchester was much more open at the time.

May 31st, 1977: Rafters, Manchester

Paul Morley review, NME, 18 June 1977

Warsaw have been searching for a drummer for many weeks, their stickman for the night uncovered only the night before. There’s a quirky cockiness about the lads that made me think for some reason of the Faces. Twinkling evil charm. Perhaps they play a little obviously but there’s an elusive spark of dissimilarity from the newer bands that suggests that they’ve plenty to play around with, time no doubt dictating tightness and eliminating odd bouts of monotony. The bass player had a mustache. I liked them and will like them even more in six months’ time.

Paul Morley: Rafters would be when Bernard had a kind of mustache, and so he looked a little bit more Pips: the shirt and the Roxy Music military thing, that was still hanging over slightly. There was a sort of odd muteness and smartness about it — it was fascinating, but they clearly dressed up too — there was a slight separation between off-duty and on. And I remember them concentrating, I remember them taking it very seriously.

They were still unformed. There was no sense that there was going to be Factory Records, for instance There was no sense that this would have any history. It was of the moment, and the moment was exciting. And here was another one, because you got excited about Manchester groups — Buzzcocks, the Fall — and in the middle of all this there was another one. I didn’t like their name, and they sounded more ordinary than not. They sounded like a rock group trying, but there was something about the trying that was interesting.

■ 3 June 1977: The Squat, Manchester

■ 6 June 1977: Guildhall, Newcastle

■ 16 June 1977: The Squat, Manchester

■ 25 June 1977: The Squat, Manchester

■ 30 June 1977: Rafters, Manchester

Richard Boon: They were very raw and unfocused, but there was an energy and a drive, which is essential. A lot of bands that formed in the wake of that early punk enthusiasm were basically talentless, but Warsaw had something: They had a spirit. Ian always struck me as being a very driven young man, and if Hooky and Barney just wanted to play a bit, he had something that he wanted to exorcise.

Bernard Sumner: I remember it being a terrifying experience because I never expected to end up on the stage when I was younger, so it was a complete surprise that it had actually happened. But it was both terrifying and very exciting at the same time, and the social aspects of it were very attractive: what it could do with your life, traveling around, going to different places, meeting people…It opened up a whole new life to me.

Peter Hook: From our first gig to the end of our first week as a group we did five gigs, and then we had a six-month lull. We did the Electric Circus with the Buzzcocks, then we had a day’s gap, and we did the Squat with the Worst and some other band — I think the Drones. Then the next day we went to Newcastle and played with the Adverts and Penetration, and we came back and on the Tuesday we played Rafters with Johnny Thunders. It was a dream come true, absolutely wonderful. People would come up and say, “Listen, there’s a punk night tomorrow, do you want to come down and play? We’ll try and give you some petrol money.” And we’d just go. It was dead free and easy.

Excerpted from THIS SEARING LIGHT, THE SUN AND EVERYTHING ELSE: Joy Division: The Oral History by Jon Savage. Copyright © 2019 by Jon Savage. Published by Faber & Faber.

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/the-birth-of-joy-division-820858/

You must be logged in to post a comment Login