“It is obvious that art cannot teach anyone anything, since in four thousand years humanity has learnt nothing at all. We should long ago have become angels had we been capable of paying attention to the experience of art, and allowing ourselves to be changed in accordance with the ideals it expresses. Art only has the capacity, through shock and catharsis, to make the human soul receptive to good. It’s ridiculous to imagine that people can be taught to be good…Art can only give food – a jolt – the occasion – for psychical experience.” –Andrei Tarkovsky

One of the most famous of all Soviet filmmakers, Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986) created just seven films in his short lifetime- all of which were masterpieces. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time (along with Ingmar Bergman, who recalled the experience of seeing Tarkovsky’s debut as ‘a miracle’, and Robert Bresson, another of his main influences as a director), Tarkovsky made films that were deeply spiritual, almost all featuring characters who are in deep existential crisis, who have an profound awakening by the end of the story.

Tarkovsky was the son of prized Russian poet Arseny Tarkovsy (whose work he included in some of his films and his book, Sculpting in Time), and was also known for his strict artistic conviction and views about the moral role of artists. He believed that ‘modern art’ had taken a wrong turn somewhere along the way, and had abandoned its ‘search for the meaning of existence in order to affirm the value of the individual for his own sake’.

Artists, he argued, were failing to acknowledge the gift they were given in being artists, and were failing to communicate to the world in a necessary way. In order to reconcile this gift, the artist must sacrifice himself and create works that teach what it means to be human; modern art had been stripped of all its humanity. Tarkovsky, like Bergman, was also accused of being too serious or having no sense of humor. His films contain very little comedic value, and meditate on serious subjects and concepts, yet offer the viewer a great sense of hope.

Nature also played a large role in Tarkovsky’s films, often being a character in itself, such ‘The Zone’ in the 1979 film Stalker. Japanese film legend Akira Kurasawa, in his obituary for Tarkovsky, explained the difficulties of filming nature and just how revelatory Tarkovsky made nature seem in his films, with how delicate he treats the subject: “If you see nature with an insightful delicacy, it follows that you treat humanity with the same kind of delicacy.

In contrast, Hollywood counterparts are, on the whole, rough and careless.” There is often a comparison to Hollywood when people talk about Tarkovsky’s films, specifically just how NOT-Hollywood they are.

This is due, one could argue, to the pacing Tarkovsky employs in almost all of his films (save for his debut, Ivan’s Childhood, which features a more conventional structure). They’re often described as languid, slowly revealing facts or clues about the characters over long scenes- but through this we are glimpsing into the thought processes of the characters, feeling for ourselves their doubts, their emotional trials, and moving through dilemmas and spiritual crises with them.

In fact, Tarkovsky even stated in his book Sculpting In Time that there must be a substantial part of each film dedicated to ”devoted to the slowly passing minutes of anticipation, delays, and pauses, which are far from being ventilation holes in the narrative progression.” This narrative progression does help us connect more emotionally with the characters, if we as the viewers are truly focused on the film. Due to the fact that, as stated previously, these are not Hollywood-type films, viewing the film can be a trial in itself.

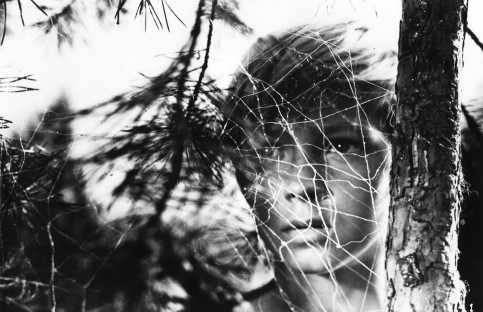

In addition to the slow pace of the films, there are often parallel narratives in some of Tarkovsky’s work, and we are sometimes unable to tell the place, time, or reality of at least one of these narratives (the scenes of Stalker’s home-life in Stalker). There is also a great deal of stark symbolism throughout the Tarkovsky canon, from tracking shots of relics underwater to burning barns, to windswept fields that somehow give a sense of menace, and seemingly haunted forests that contain no signs of the war they contain.

The profound experiences of Tarkovsky’s characters are often reflected in these symbols, as well as nature’s profound experience as affected by human nature- it is hard not to see the famous dream sequence in Stalker, in which tools created by man (a mirror, a syringe, money, a religious portrait) are shown rusting in a shallow pool of water, rendered meaningless, or at least useless, in the face of the great mystery of the zone. It is among the most enduring images in cinema history, and deeply moving.

Like other titans of film such as Orson Welles and Francis Ford Coppola, Tarkovsky often had issues with the creative control of his films, as Russian censors felt his films too spiritual in content for the atheist and authoritarian ideals of the Soviet Union. This led to the limited release of many of his early films, including his second film, Andrei Rublev- the film was completed in the summer of 1966, but only received one initial screening that year, and didn’t get an official release in the Soviet Union until 1971 (two years after it won the critic’s prize at Cannes, at the 1969 festival).

The film was also cut by 40 minutes when it was finally released in the United States, and a whole hour was taken off the film when released in the United Kingdom in the early seventies. He would often not get the final edit. In the early 1980s Tarkovsky exiled himself to Europe in order to escape the oppression of his art, and completed his last films in Italy and Sweden. He succumbed to lung cancer in Paris, France at the age of 54.

In Chris Marker’s documentary film One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich, which has footage of the dying filmmaker in the last stages of his life, there is a scene explains that at one point, a fortune teller informed Tarkovsky that he would complete only seven films in his lifetime.

The dying filmmaker could as least die knowing they were all good films, and you can go further by saying that these seven films add up to almost a complete life’s work, everything leading up to his final masterpiece in 1986, the transcendental film simply called The Sacrifice. One can almost get the sense that, through his work, Tarkovsky was more aware than the rest of us that he was on borrowed time, and did in fact make a complete artistic statement.

1. Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

After five intense years of study at the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (now known as the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, or V.G.I.K.), Tarkovsky set out to make his first feature length film. A World War II film that depicts the human cost of war, this is one of several Russian films of the time period, as it was a way that many new directors tried to break in. What sets Ivan’s Childhood apart, however, is the film’s visionary style and beautifully rendered depiction of a youth destroyed by the horrors of war, and innocence lost.

Ivan, the protagonist, is a 12-year old boy, working as a spy for the Russian army. Having both his parents and his sister killed in the war, he has made it his life’s mission to seek his revenge. His soul has become rotten, and he is completely consumed by the desire for vengeance.

The Russian military, despite taking advantage of Ivan’s tiny size for reconnaissance mission, tries to send Ivan to military school for safety, but the boy insists on remaining on the front lines. We see a negative force burning through his piercing eyes, his weary movements (that seem so strange for a child, his energy seems reserved more for a bitter old man) and general malaise.

In its 1963 review of the film, the New York Times called Ivan’s Childhood a “cry of anguish for all youngsters lost in World War II, for the youths whose lives were exhausted in hatred, bloodshed and death.” The sense of internalized violence is portrayed through the dream sequences of the film, which interspersed with the bleak scenes of war and Ivan’s current reality show us what really gets lost through the carnage of war- innocence.

The film won the Golden Lion award at the Venice Film Festival (tied with Valerio Zurlini’s Family Portrait), and staked Tarkovsky’s place in International Cinema. It also won awards at the San Francisco International Film Festival, and was selected (but ultimately not accepted) as the Russian candidate for the Academy Awards.

It also was highly acclaimed among the intellectual community at the time, including a piece defending the film written by Jean-Paul Sartre, as well as praise by filmmaker Ingmar Bergman. Tarkovsky later found himself displeased with some of the creative decisions on the aesthetics of the film, but it remains one of the best debut films of all time, and a highly poetic depiction of war through the lens of youth (however broken that lens may be).

2. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Tarkovsky first proposed the biopic on famous 15th century Russian icon painter Andrei Rublev in 1961 to Mosfilm, and spent the next two years writing the script with co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky, poring over medieval documents and texts on medieval life and art.

After two years of filming, the art-house epic was finally finished, running almost three and a half hours in length- would only get one showing until nearly four years after filming was completed. Andrei Rublev is clearly a labor of love and incredible inspiration, and surprising has very little to actually do with Andrei Rublev.

What Tarkovsky meant to do with the film is to show the connection between and artist and his times, showing the limitations and development through these limitations. He has little interest in making a straightforward biographical film- Rublev isn’t show actually painting anything, and even goes through a vow of silence during the film – the opposite of a typical Hollywood biopic, with little-to-no story arc; Rublev is simply observing his surroundings through most of the film, and not necessary involved in the action we are seeing. Like the rest of the films in Tarkovsky’s career, this is more about Tarkovsky than it is about Rublev- it’s his reactions to what he sees in Rublev’s work.

The film took three years to get a proper release, due to the Soviet government’s attempts to secularize Andrei Rublev’s work and make him more of a national hero than religious one. Tarkovsky himself dealt with the government censors, as they saw his film as being too religious for release.

Placed in context of the Soviet Union at the time, argues University of Chicago Slavic Languages Professor Robert Bird, “it is a completely unique film.” There were no other films during this time dealing with religion in a sympathetic way. In this, along with its stunning visual style and unique non-linear narrative, Andrei Rublev is a masterpiece, and arguably the greatest ‘art film’ of all time.

3. Solaris (1972)

Though this is Tarkovsky’s first foray in the science fiction genre, Solaris seems much more interested than the inner regions of its characters minds than outer space. Tarkovsky decided to make Solaris as a reaction to the sci-fi movies coming from Hollywood, calling Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey “sterile and cold”, and felt the genre itself was shallow. Solaris begins as an anti- science-fiction film: shots of nature, warm light, and water. This sets the tone for more grounded, internalized type of science fiction.

The films revolves around Kris Kelvin, a psychoanalyst sent to the space station hovering over Solaris, a body of water located deep in space that has some sort of cognitive abilities, a sentient being in its own right. Kelvin is sent by the head of the organization responsible for initial study of Solaris, and he must determine whether or not the station or overall mission is even worth continuing at all.

However, once Kelvin gets to Solaris he realizes that it has the ability to not only probe one’s mind, but manifest those it finds in the deepest recesses of its subconscious. Kelvin starts seeing his dead wife, who had committed suicide sometime before our story begins.

The film brings up a universal and very big question, one that the sci-fi genre rarely scratches the surface of: what does it mean to be a human, and does a physical body account for one’s soul? Or is it something else? The film also explores the meaninglessness of technology, and how it brings us further from nature and our true selves.

The film was a commercial and critical success. It debuted at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, and won the Grand Prix award in addition to being nominated for the Golden Palm, the festival’s highest honor. The film also sold over 10 million tickets in its initial, fairly limited release in Russia.

Despite the success, Tarkovsky later felt that the film was a creative failure, citing his inability to ‘transcend the genre.’ His view was that it a director ‘is not entitled to please anyone’, and that making art for the appeasement of others restricts the artist; the fact that his pictures were a success in a critical or commercial sense had no bearing on his personal opinion of the film.

4. The Mirror (1975)

After the successful Solaris, Tarkovsky starting work on The Mirror, a film based on a decade-old concept he had for a film about a man’s memories and dreams, from the point of view of the man, without showing him in the film. Coming back to this idea after making two films, the Mirror can be read as a dying man’s recollections of his past, moments in Russian history, and his personal history. The film is also one of Tarkovsky’s most personal, and poetic, works in his can.

Aesthetically, The Mirror is very unique: it shifts from sepia tone, black and white to color, mixing archival footage amongst the flashbacks of a dying poet. The style has been compared to stream-of-consciousness writing, and is extremely powerful in its effect. The plot is not easily ascertainable, flowing in and out of different points in time, much like the writing of Marcel Proust.

Full of the characteristic stark imagery and symbolism, The Mirror remains one of the most beautiful, if incomprehensible, films of all time. Audiences received the film well upon its initial release, but it would has been the subject of fierce debate- The Russian State Committee for Cinematography wouldn’t allow the film to be shown at Cannes in 1975, and had made it quite difficult during through the whole process for Tarkovsky to get the film done. It is now recognized as one of the great films in cinema history, often finding its way onto many ‘top 10’ lists.

5. Stalker (1979)

Whereas Tarkovsky felt he had ultimately failed with the science fiction genre with Solaris, he felt differently about Stalker. Tarkovsky’s second take on the science fiction genre is a poetic, highly allegorical film that explores the purpose of art, as well as human desires and what we really need to be a human. Slow and deliberately paced, there is next to no action at all, with an atmospheric soundtrack, showing us that Tarkovsky is attempting to completely distance himself from the genre and put forth and profound and entrancing work.

The plot revolves around three characters: Stalker- who leads people through the mysterious ‘Zone’ (a heavily guarded area that is rumored to contain a room within which dreams are fulfilled, and have the implications of nuclear fallout), the Writer – a bitter man who wishes to obtain genius to make up for his waning inspiration, and the Scientist, a grounded man who wishes to win a Nobel prize.

Stalker serves as their guide (in more ways than one) through the eerily quiet ‘Zone’, which is be guarded by its own unpredictable and obscure traps, while along the way the two guests ponder their desires and the true worth of what they wish for.

Again, Tarkovsky faced criticism from the authorities, this time for the films pacing. The Committee for Cinematography called the film too slow and dull, to which Tarkovsky replied that their opinion did not matter to him. It would be the last film he made in the Soviet Union. Dreamlike, arresting, and gorgeous, Stalker is a masterpiece of the science fiction genre, despite of (or because of) its deviation from the genre’s typical aesthetics.

6. Nostalghia (1983)

His first film directed outside his home country, Tarkovsky directed Nostalghia in Italy with the support of Mosfilm, who eventually backed out. He eventually found support from Italian State Television and Gaumont (a French studio), creating a work about “the fatal attachment of Russians to their national roots, their past their culture, their native places, their families and friends.”

Tarkovsky made a ‘profoundly Russian’ film while in Italy, about a Russian weary poet who goes to Italy to research an Italy composer from the 1700s for an opera libretto, before returning to end his own life home in Russia. He’s detached, disoriented, and longing for home. The film greatly mirrored Tarkovsky’s own life for a time. He wrote of the period when he initially left Russia as ‘like a symptom of the hopelessness of trying to grasp what is boundless.’ The film shows what it’s like to be intensely aware of being an outsider.

For Nostalghia, Tarkovsky received further honors at Cannes, even sharing a special prize with one of his film idols, Robert Bresson. However, Russian authorities again blocked Tarkovsky from being eligible for the festival’s highest honors, the ‘Golden Palm’, even though claims to have been making the film for his compatriots with the hopes that it would be shown in Russia.

7. The Sacrifice (1986)

Tarkovsky’s final film was made in Sweden on an island off the country’s Southeast coast, and starred a Bergman regular, Erland Josephson. The film is about a man’s bargain to God in order to stop the impending doom that has just come on the radio- a possible nuclear Holocaust.

Josephson stars as an ex-actor turned intellectual named Alexander, and his family who lives on a remote island. While the family’s postman over, it is announced over the radio that doom is near. The postman convinces Alexander he must go to bed with the family maid, whom he claims is a witch. Despite initial reluctance, Alexander and his maid consummate in an ethereal scene in which they levitate on the maid’s bed.

In the end, Alexander sets him home ablaze (after convincing the family to go for a walk), eventually getting taken away by an ambulance. In fact the film speaks of man’s loss of will to materialism. In an Interview, Tarkovsky explained: ‘I wanted to show that man can restore his links with life by renewing his covenant with the source of his soul,’ in which case Alexander’s sacrifice can be seen as one of those links.

Released in May of 1986, the film was positively received again at Cannes, winning another Grand Prix award, and was also a BAFTA winner. Tarkovsky would die of cancer just nine months after the film’s release. However, his seventh film does complete one of the best oeuvres in cinema history, and cements his place as one of the greatest directors of all time.

Sam Perduta

source: Taste of Cinema

You must be logged in to post a comment Login