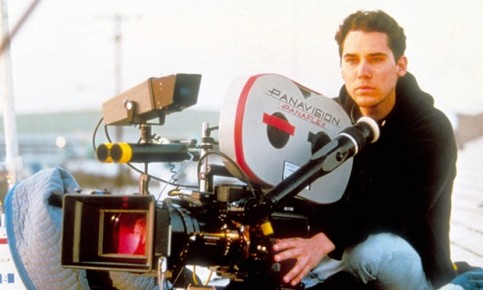

Bryan Singer, director

Chris McQuarrie rang me up after he’d written about 50 pages of the script and said:

“What if the villain pulls the whole story off a bulletin board?” And I replied: “Now that’s a reason to make the damned movie!”

A lot of the inspiration for Keyser Söze, the villain, came from the character of Yuri in the 1980s thriller No Way Out – a spy within the Pentagon who may or may not exist. Söze was written with Kevin Spacey in mind: he’d approached me at a screening and asked to work with us. He wasn’t so famous back then and we thought he’d be great, since we’d loved him in Glengarry Glen Ross. There’s something sly and fun about him that’s perfect for a trickster mastermind like Verbal.

I sent the script to over 50 studios and potential funders, all of whom rejected it. We had some financing, but that fell through, too. I remember we’d all got together to do some early preparations in Arnold Schwarzenegger’s building in LA, the one that housed his restaurant Schatzi – and they just shut the power off. The thing that saved us was Chazz Palminteri. He agreed to play the cop, but he had a very tiny window in his schedule, just two weeks. So the studios knew they had to move fast if they wanted the chance to fund a film with such a bankable star. PolyGram and Spelling Films ended up giving us $6.5m and we shot the whole thing in 35 days: 33 in LA, two in New York.

Benicio del Toro had been watching an old Stanley Kubrick film called The Killing. There’s a character in it who speaks with his teeth clenched throughout and he thought it would be interesting if he made Fred Fenster, the crook he was playing, hard to understand. I thought Chris and he were playing a joke on me, but then I said to myself: “Is there anything Fred says that we need to know? No – he’s just here to die!” So I said: “Go for it.”

While we were filming the climactic scene around the docks after dark, the authorities received an anonymous call saying there were either drugs or guns on the boat we were using, a 220ft minesweeper once owned by the Kennedys. So the ATF – the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives – raided the boat and shut down the movie. I decided to just go for a walk and rewrite the entire third act in my head. But one of the producers woke up the mayor and we got permission to carry on.

We finished editing two weeks early, but the film kind of died at the end, during the big reveal. Then I had an epiphany while lying by the editing machine in my sleeping bag. You finally understood that Kevin, not Gabriel, was Söze – but you didn’t feel it viscerally. So I said to my editor: “Find me images and sounds that show Kevin is Söze. Cut them into a montage and run it just as Chazz’s cop looks at everything on the bulletin board and realises.”

Gramercy, the distributor, had no idea what they had. The film was only shown in about 900 cinemas and, in terms of box office, only did about $60m. But it soon became clear we had a phenomenon on our hands. The Usual Suspects was on hundreds of Top 10 lists and, after winning two Oscars in 1996, became a video hit and a cult classic. Bill Clinton was a huge fan, because Chelsea loved it. He kept a copy on Air Force One.

Gabriel Byrne, actor

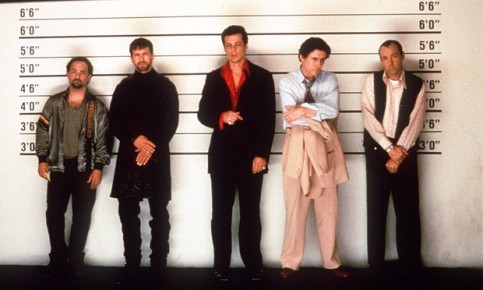

We did the lineup scene in a post-lunch, giggly kind of atmosphere. Bryan kept losing his temper with us, coming over all schoolmasterish, and we tried to get serious. But Benicio farting broke the tension, as farts tend to do. And fair play to Bryan: he left the camera rolling and kept it all in the film. What works brilliantly about the scene is the camaraderie, the sense of a shared past between the characters.

I was laughing all the time, every day of shooting. I used to film my own footage: I’d get about two hours of Spacey and Kevin Pollak, who played wisecracking Hockney, acting the goat every day. They’re brilliant impressionists and would be duelling away, hogging the limelight. Myself and Benicio were a little quieter, though Stephen Baldwin, who played McManus and was still in his pre-born-again days, was a rampant eccentric, a hilarious nutjob.

When I first read the script, I found it a page-turner. That’s always a good sign with a thriller. But when I got to the end, I thought: “I dunno. The guy reads the plot off a wall and then walks away without a limp? Hmmm.” But Bryan persuaded me. I did actually pull out of the film a little before shooting, though. My marriage had just broken up and I was pretty exhausted. I just wanted to be with my kids.

When you’re in a thriller, you have to know the rules – then forget them and just react to what’s happening. There’s a scene where a thug flicks a cigarette and it hits McManus right in the eye. That wasn’t planned. And in the lineup, a policeman says to Hockney: “We can put you in Queens on the night of the hijacking.” He replies: “Really? I live in Queens. Did you put that together yourself, Einstein?” All improvised.

Afterwards, I think everyone felt a bit sceptical: how could a film we’d had such a good time shooting be any good? But we just knew from the silence throughout the screening at the Cannes film festival that people were absolutely engaged. We were the toast of the town. It was a very heady feeling, with all the guys competing to see who’d got the most phone numbers slipped into their pockets.

It’s amazing the effect the film still has. Even people who have seen it five or six times say to me: “I know who did it, but I still get a surprise.” I was filming in New York last year and this guy came up to me and introduced his friend, who was blind. The blind guy started to recite all the dialogue from the film. I said: “You know the lines better than we did.” And his friend said: “That was the last film he saw before he went blind.”

Interviews by Phil Hoad

You must be logged in to post a comment Login