There are two main images that instantly rise to mind when the words “Serbia” and “Cinema” appear together: the controversial “A Serbian Film” by Srdjan Spasojevic and the face of one of the most talented directors that Europe saw born in last decades, Emir Kusturica. For now, let’s just forget the blood and necrophilia of the 2010’s film and focus on Emir’s world vision, his identity, obsessions, existentialism and Balkan culture.

Offering viewers a ticket to a baroque, surrealist and never-before-visited reality, Kusturica likes to blend his stories and characters with unique visual elements, always building an atmosphere full of traditional lifestyles that glisten in the background.

Highly influenced by all types of art, such as painting, sculpture, literature or cinema, Kusturica usually mixes authors and art pieces with his imagination or with his Balkan culture, conceiving cultural products with a kind of aura.

As a lover of life and creative freedom, this Serbian seeks to employ realism seasoned with dreams and desires that are familiar to any people, nation, ethnicity or country. He does this by painting individuals exactly the way they are: drinking, dancing, laughing out loud, fighting and fornicating.

Other notorious trait that makes Emir Kusturica special is his curiosity and constant interest in seeing, listening and experiencing new things, which is why he enjoys being self-taught and tries to do many things in many areas. The “jack of all trades” is always seeking to express himself through many disciplines, and he currently is a filmmaker, musician, writer and architect.

In the end, all of Kusturica’s efforts concentrate on the aforesaid cultural differences, the beauty of diversity, and an obsession with allegorical thinking. Because of this, it’s not strange at all if in the same film we see artistic features of authors like Magritte, Buñuel and José Saramago or Akutagawa, all embraced in one of Kusturica’s plots.

Besides being recognized as one of the most fascinating and original storytellers of our time, Emir is also widely lauded by critics, and he has won multiple awards during his career. His name is part of the small range of filmmakers who have won the Palm D’or twice, along with such names as Michael Haneke, Francis Ford Coppola or Shohei Imamura.

Ultimately, Kusturica’s films didn’t have the impact of the past, but the director is planning a new story about war, love and drama that is expected to be released within this year. More than with prizes and awards, Emir Kusturica’s filmography deserves to be appreciated with sensibility, a sense of humor and cultural openness.

This list is a summary of the exploration of new feelings, cultures and behaviors that Kusturica’s genial and purposefully naïve mind has expressed through characters and symbols. Welcome to the universe of Emir Kusturica, where every story is a trip with no scheduled return and no charge to ride.

1. Guernica (1978)

Emir Kusturica started to show his style and sensibility at a young age, surprising his professors and others around him. At the age of 24, Emir was already working for Yugoslavian television, making films and intimately learning the seventh art.

During that learning period, there is a short movie that shares its name with a Picasso painting and synthetizes the entire world vision that is so characteristic of Kusturica. “Guernica” takes us to our childhood innocence, in which every day is an adventure that brings new unanswered questions.

The story takes place during World War II and tells the story of a Jewish kid who is fascinated by Guernica’s world. Roger presents himself as a curious child – always asking questions and exploring everything he sees – and he may be a representation of how Kusturica was as a child.

The film has a very simple aesthetic, using black and white to guide an existentialist story about day and night, lightness and darkness, fear and courage… Those colors (or the absence of color) capture the central idea of the film: contrast. While the kid is fixated on Picasso’s “Guernica”, the story is involved in poetic dialogue and metaphorical speech that euphemistically convey the World War II paradigm.

Within 17 minutes, this short has lots of hidden meanings that constantly ornament the narrative, perhaps because this is not a World War II story but rather a portrait of the complexity of the world and the differences between men. As George Orwell writes in Animal Farm, “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

In the same way Roberto Benigni creates an imaginary game to protect his son in a concentration camp in “Life is Beautiful”, in “Guernica” we see Roger’s father inventing a club where everybody needs to use a ribbon to be a member. The difference between the films is that Roger’s father ends his conversation with one of the strongest lines of the movie: “We are Jews, do you understand? Impure and inferior race.”

Another epic and poetic line occurs when Roger asks his father why Picasso painted Guernica the way he did, and the man replies that “when Nazis asked him recently if he painted it, he [Picasso] replied: no, it wasn’t me, this is your work.”

We know Picasso painted Guernica as a response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque Country in Spain, but no one knows if “the man that has no fear of the dark” really told that to the Germans; nevertheless, it remains a wonderful line.

This first effort by Kusturica turns out to be more an artistic work than a simple story, since it thoughtfully combines all of its elements to create a holistic concept: contrast. All is connected: from Roger’s questions to his parents’ difficult decisions, or from the cubism of Picasso to the cuts that Roger makes in his family pictures.

Guernica’s atmosphere lives in this short film, and the Jewish boy lives in that painting. At the end of the day, all is easier when we are little and the world is beautiful.

2. Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (1981)

Although Kusturica is seen as a Serbian citizen, he was actually born in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and he truly respects his Bosnian roots. Hence, his first feature film takes place in Sarajevo during the ‘60s, and it was a pleasant surprise not only in Europe, but everywhere that it was distributed.

“Do You Remember Dolly Bell?” tells the story of a Yugoslavian boy who gives shelter to a friend’s prostitute and ends up falling in love with her. But, obviously, there is much more than this…

Dino is a teenager who is interested in hypnosis and the prospect of manipulating others with it, but he fails to use it properly while learning some important lessons about life, politics, crime, addiction and women. The evolution of Dino’s character is remarkable during the film and so are the conversations he has with his father, a tough-but-fair and bizarre man.

The ethnicity and cultural habits, as usual with Emir Kusturica, are well expressed throughout the entire film, particularly in the family dinners and in some small crimes that the characters commit. Yugoslavian teenagers are so criminal that a dance club is created to distract them from their bad habits; this club turns to be very important for Dino’s life.

Some supporting actors are not very good, but that is forgivable thanks to the powerful feeling that Kusturica offers with his sober, realistic way of filming and the atmosphere created by the energetic way people smoke, drink, sing and dance, all of which is so strange to occidental people. Music has an important role in the film.

At one point, Dino plays guitar, and he also likes to sing an Italian ‘60s hit called “24,000 Baci,” which means “24,000 kisses” in English and is a really catchy song. The soundtrack by Zoran Simjanovic includes some Gypsy tunes that convey happiness and festivity during some dark and sad events.

Music also serves to show the culture of these richly-characterized places, where all the people know and talk with each other and where the sounds of carousels and loud music fill the air.

“Do You Remember Dolly Bell?” is also a funny sketch of how life was in Eastern Europe at the time. Dino shows us such youthful hardships as his first cigar and his treatment at the hands of his aggressive older brother and peculiar father.

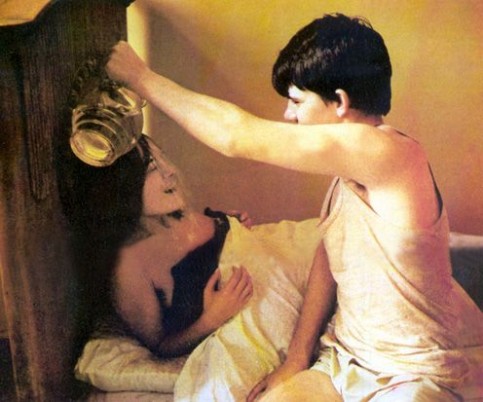

The movie also portrays an interesting discovery of the opposite sex, as Dolly Bell has a very important part in Dino’s life. Kusturica crosses the physical attributes of Dolly Bell with the beautiful mind of Dino, piecing these aspects together as the characters come to know each other. The sexually naïve and ignorant boy serves as a symbol to the period when sex was taboo and teenagers were not informed about such matters.

The film’s entire 110-minute duration exudes that Gypsy culture, full of people eating with their hands and with wide-open mouths as they talk endlessly about communism. Using Dino’s love for hypnosis, Kusturica compares a communist leader with a hypnotist, since both must manipulate other people.

Emir pays a proud tribute to his home country of Bosnia, in other words, to a nation full of joy, quick rhythm, vertiginous dancing and… a poor, sad life. During the film, Dino repeats constantly to himself that he is “improving every day in every way.” Kusturica managed to do the same.

3. When Father Was Away on Business (1985)

In 1985, Emir Kusturica returns to one of the most important and historical rich cities of the Balkans, Sarajevo. Influenced by a Dragoslav Mihailovic novel, which talks about an infamous concentration camp, and working again with Abdulah Sidran, Emir offers to the audience “an historical love film”, as he says himself at the very beginning of “When Father Was Away on Business”.

The Serbian filmmaker remains loyal to his principles and cultural values, developing one the best and most realistic traditional films ever made in Europe and perhaps worldwide.

This is a film where Emir Kusturica builds a portrait of the conflict between Stalin and Tito during the Cold War period, through the eyes of the 6-year-old Malik Malkoc. “When Father Was Away on Business” is colored by its use of traditional music and its themes regarding the true value of labor and family. These were the times when Stalin was a God, Tito was a prince and people were… poor.

With the break-up between Tito and Stalin, those who once deified the Soviet in Yugoslavia now become the ones who shout “Kill Stalin!” This was a situation that affected everyone, not only the politically active people, but even those who were uninvolved in politics. In those dangerous years of strict rationing, deprivation and conflict, we can see the importance with which people treated radio, football and alcohol. (Yugoslavians were champions at drinking.)

The Serbian director has the virtue never to put too much hatred in this story, which we see through the eyes of an innocent child who is a chronic sleepwalker. For Malik there are lots of more important questions than this political fait diver and, even for those who are not interested in the subject, the story told from a kid’s perspective can always be understood or, at the very least, accepted.

The second feature film by Kusturica shows us also the sensation of guilt one may feel without being even remotely connected to the communist political system. Mainly with the character of Mesa Zolj (Malik’s father), Emir Kusturica plays with our emotions and suddenly the concepts of right and wrong, fair and unfair, and innocent and guilty become clouded and uncertain.

In “When Father Was Away on Business”, humor and sorrow blend together, for this is a film that considers a very serious subject but always has some comedy in its core. We laugh at and with the characters, at the same time we feel pity for them because we know they are not really happy.

In this movie we also have some excellent performances by Predrag Manojlovic and Davor Dujmovic. Davor’s character, Brat Mirza, was the quiet and the most unnoticed role, but the wisest and the most interesting at the same time. It was a pity Emir didn’t explore this character a little more.

With this carnival film, we return to the roots of cinema by using a powerful sense of time and place in the story, a technique that was all too forgotten in the mid-eighties. Emir admits that in every film he takes a little bit of this family story to the movie, even if that little bit is purely fictitious.

On that basis, Kusturica can easily put the spectator inside the film, witnessing the first love of Malik at a time when politics are everywhere and cheating is a banal thing. We feel that we are really there, in the ‘50s, surrounded by a Balkan family as we watch a barber perform a circumcision on two little boys.

Kusturica has centered his attention on the family in order to create a certain mythology about this terrible era of cruelty, pain and poverty, and this enchanting method earned the Palm D’or for the Yugoslavian film.

4. Time of the Gypsies (1988)

Unlike his other films, which were based on Emir Kusturica’s life and origins, this is a movie about a subject that didn’t affect Emir directly. “Time of the Gypsies” tells the story of Perham, a poor Gypsy boy who is quite different than those around him.

Between his artful blend of genres and his story about a life of gambling, religion and superstition, Emir creates the same film he had made in “Do You Remember Dolly Bell” and “When Father Was Away on Business”, but with another story, another intention and a distinct meaning. The filmmaker joins humor with tragedy, luck and chance as he portrays multiple conflicts centered around God and the Gypsies, a poor people that were forgotten by God.

Davor Dujmovic, who was an amazing actor, plays the role of Perham, an honest Gypsy whose life is surrounded by crime, gambling and cheating. When the boy falls in love with Azra, he tries to marry her, but her mother firmly refuses the marriage proposal because Perham doesn’t have anything to offer: no money, no job and no future.

The Yugoslavian Gypsy community express their feelings very directly and speak straight from the heart, which creates some very funny moments over the course of the story. American movie stars are widely idolized and serve as the sign of these people’s dreams. Emir is a person that understands the relationship between sound and image, so he uses a large range of Gypsy music to energize the story and set the mood for an unfamiliar reality within a traditionally rich story.

The Gypsies are connected to many stereotypes that are not always truthful, and this film demystifies some of them. The traditional music is also responsible for the film’s frenetic rhythm, in other words, the film is so fluent and mordant, that seems to have three or four hours of runtime.

“Time of the Gypsies” has some similarities with “The Godfather”: at first Perham is against crime like Michael Corleone, but ends up being corrupted by the mafia system. In this arc, we can see the value of money, which doesn’t buy happiness but buys respect.

Once more, Kusturica tries to employ a contrasting point of view, showing a criminal and decadent environment through the eyes of an honest and uncorrupted individual. In “When Father Was Away on Business”, he creates the same effect with Malik. Another strength of the film is the amount of feelings that jump outside the screen.

Thanks to a great performance by Davor Dujmovic, we are able to feel the pain, the love, the sad goodbyes and the powerfully tragic fate. There’s also something Freudian about Perham in the way his dreams show the beauty of his mind, which is full of fears, desires and fantasies.

In the world of vagrancy, slavery, larceny and prostitution, there is endless swindling and trickery, which is very funny to watch and consider. The nudity, so typical of the European cinema, is very natural and innocent in pieces by Kusturica, ensuring the realism that is needed in this kind of film.

Breasts are not always an erotic and pornographic object, they can simply be part of reality or, within the right perspective, art. In a story of redemption, the Serbian director shows us how funny it can be when we become what we most despise. “Time of the Gypsies” is a burlesque comedy-drama, based not in a Greek, but a Gypsy tragedy.

5. Arizona Dream (1992)

When “Arizona Dream” was released, the reviews were like the movie itself: bittersweet. While the film was not well received in the US, in Europe (especially in France) it became a cult film, one of those that does not appeal to everyone.

Even on American soil, Emir Kusturica continued to have his own peculiar vision of the world, and his artistic touch, which did not rely on tired cinematographic formulas, was strange to some American critics, who were not used to this kind of cinema. Truth be told, this is one of the most complex, artistic, surrealist and abstract films ever made by Emir Kusturica and, therefore, one the most underrated movies of his filmography.

In Emir Kusturica’s fourth feature film, everything can have a second meaning, but the one central concept remains: “What is life?” The cast is great, starring with Jerry Lewis, Faye Dunaway, Lili Taylor, and, above all, Johnny Depp and Vincent Gallo, who are perfectly-suited to the script’s demands.

Vincent Gallo offers a colossal performance as Paul Leger, an expert in cinema who provides many good laughs during the movie, but it’s impossible to overshadow Johnny Depp as the big star here.

We all know Depp is capable of an amazing metamorphosis into a role, but most people did not foresee that he would fit so well into Kusturica’s metaphoric vision of the world. Seeing Depp starring in truly artistic cinema is a pleasure to the eyes, and, with such a strong character in “Arizona Dream,” he really shows his talent and versatility, even imitating a chicken in a must-see scene that was, in fact, improvised.

Kusturica builds an existentialist poem and it’s really amazing how, time after time, he can always transmit strong emotions to the audience. The feeling of being alone among lots of people, that sense of being just a small point in the infinite universe and the uncertainty of what the future holds for us… All this is in “Arizona Dream” on a subliminal level.

If we compare the sad figure of Axel in the start of the movie to his persona when he smokes three cigars at the same time, we understand that life is a little like that: just a series of very different moments. This is why there is something truly remarkable and special that invigorates Emir’s story.

The filmmaker asks some questions about men’s weaknesses, the fear of dying, what happens after death, the pain of being alone, etc. The answers are offered philosophically through a “men vs. fish” comparison.

In his line of reasoning, Axel states that, usually, people say fish are stupid, but they are wise because they know how to be quiet and don’t need to analyze and think about everything. He goes on to argue that humans are stupid because we think too much but still don’t have a clue about what are we doing in life.

The movie shows this ridiculous face of the human being: the insecurities, the vanity and the desire to present something fake and superficial. There’s a fish that appears many times throughout the film, swimming in the air, and that image of the fish flying is the metaphor that Emir Kusturica uses to complete his “meaning of life piece of art.”

People are like fishes, they are just travelling aimlessly, trying to find a good reason to swim, but they don’t really know what they’re looking for. Axel thinks people all wish they could be “flying in love”, instead of falling. But, according to Kusturica, “life is all dreams.” If that’s true, then this film, too, is a mere dream.

6. Underground (1995)

At first, this film looks just another adventure by Emir Kusturica, but that appearance is just an illusion. “Underground” was very controversial when it was released because some critics said that it was a movie “full of pro-Serb propaganda,” but ultimately Kusturica had created another cinematic success and won his second Palm D’or.

Considered by many to be the magnum opus of Kusturica, the 1995 film shows a wiser and more mature director, who has developed a great arsenal of filmmaking techniques. Clearly influenced by Tarkovsky, Fellini and Renoir, Kusturica moves away from the Dusan Kovacevic novel and from the script too, relying heavily on improvisation to craft a story about two friends – Blacky and Marko – who are in love with the same woman, a great Yugoslavian actress.

Kusto divides the film in three parts: War, Cold War and… War. With this structure, the movie is a very creative lesson about European history, as the story transpires through three important war periods of the twentieth century: World War II, the Cold War and the Yugoslavian Civil War. But this film is not about a certain moment or a certain place, it exceeds the boundaries of time and space.

There’s always something happening as the characters form a new plan, and that makes the film very rich in content. The use of certain levity results in a comic side of war that is very interesting to see, such as when Marko is idly masturbating during a bombing that causes many deaths just outside his door.

As in his previous films, Emir Kusturica uses lots of singing, dancing and politics, retaining the same goofiness and all the ingredients that he usually uses in his stories.

At some points, it is easy to feel a little lost in this film because certain events occur without logic and explanation, but then we simply have to connect the pieces ourselves and voilá, all makes sense. Without doubt, this is an art film in all aspects, and such an approach is not always well received by the general public.

In the movie poster, we can read “one of the great films of the decade”, but I would risk saying this is one of the greatest films of all time. Even the apparently trivial moments can be important for the film’s overall intent and narrative, and this subtle and purposeful style captivates the full attention of the spectator.

It’s easy to find some similarities with Wolfgang Becker’s “Good Bye Lenin!” since there are two different realities in conflict: the familiar one, where the previous war is over and life is full of paranoia because of the Cold War, and the underground one, where people think World War II is still happening up above.

“Underground” is an energetic and tragic affair with an abundance of both smiles and tears and where danger, energy, freedom and claustrophobia share the same space. In its light and creative way, this piece shows how people’s fanaticism can run to a tragic end for those we love most, however unintentionally or unconsciously this may develop. Whatever happens, our thoughts and minds still depend on the most important things: memories, feelings and emotions.

Above the narrative’s events, there hovers an intriguing line that has a striking level of beauty and sadness: “there’s no war, while brother doesn’t kill brother.” This is a very special effort by Emir Kusturica and the movie that took him to a high level of cinema, etching his name into the history of film and ensuring that he will be remembered.

7. Black Cat, White Cat (1998)

First of all, “Crna macka, beli macor”, the original name of the movie, is a far superior title for this Gypsy story in comparison with the English translated one. This is primarily because “macka” is a feminine cat and “macor” is a masculine cat, but in English we can’t get that same contrast so easily, so we lose a little of the meaning.

In the same pattern of Emir’s early works, “Black Cat, White Cat” is a rude, violent, filthy and culturally deep film that focuses on the Gypsies’ dark business, their culture, their festive way of living and, of course, their strong emotions.

The film’s content is based in surrealism, as portrayed through the characters and scenery along the coast of the Danube; additionally, the plot begins constantly jumping into distant realities near the end of the film. This film is more “in your face” than others, and this leads the viewer both to an easy comprehension and to big laughs, ensuring that “Black Cat, White Cat” is one of the best and funniest films by Emir Kusturica.

The notion of perspective is the crucial to the film. Kusturica starts by sharing only a few frames from different stories, giving the viewer certain clues of how things will end. Within stories of Gypsy mafia, crime and deception, love remains the driving story element in the relationship between Ida and Zare, two poor Gypsies who love each other but whose fates are controlled by money and powerful interests.

Despite the gravity of their love, all this is narrated with a comic spirit, and this is what people really enjoy in the film. With lots of good laughs and the lead actor of “Serbian Film” offering an excellent performance, the film escapes from the stereotypical expectations of a comedy, thanks as well to the Gypsy culture reflected in the movie and to the music used throughout, such as the “Pitt Bull Terrier” theme.

The use of contrasts is, again, very well employed by Kusto. We see rich people living with poor people, criminals in conflict with an honest man, Zare, and the stereotype of submissive women, which we also see in “Time of the Gypsies”, in stark contrast with Ida, a rebellious, independent and self-motivated Gypsy girl. All those contrasts are symbolically represented by the image of the black cat and the white cat.

The concept of true love does not strike the viewer as a cliché, occurring as it does in the middle of crime and vagrancy, although Kusturica does not fully explore the emotional aspect of the film. What matters here is the story itself, the marriages that occur within three days, and the laughs provided by all the characters.

When all these elements combine, “Black Cat, White Cat” is a straightforward story where, in the end, love wins over money, the good are happy, and the bad are left in a nasty situation. Kusturica doesn’t close the film with an ordinary “The End”, but with a “Happy End.” This sums it up quite nicely.

8. Life is a Miracle (2004)

“Every film that I was doing is almost the same movie in different faces, different approaches.” Like a painter and his favorite subjects, Kusturica was always exploring the same concept throughout his filmography, but with distinct nuances and subjects. By creating many movies with a traditional atmosphere and a cultural strong feeling,

Kusturica became a master in this style of art film. Indeed, “Life is a Miracle” isn’t the best “Balkan film” made by Kusturica, but it is a movie that shows a mature director who knows what he is doing and who can turn a bizarre and baroque plot into a naturalistic story. This maturity and this strong craftsmanship eliminate some potential naivety from the film, and that’s an innovation here.

This is another film that takes place in… yes, you got it, Bosnia. “Life is a Miracle” is very visual and utilizes all of Kusturica’s usual ingredients with a very imaginative story that incorporates football, music, war, politics, rhythm, surrealism and Balkan culture.

This 2004 film is about the Bosnian war, which occurred from 1992 to 1995 and pitted Bosnia against Croatia and Serbia, and tells the story of a dysfunctional family that ran out of Belgrade and later regrets their actions. Again, we notice that Kusturica likes to promote his actors from supporting roles to main parts.

Slavko Stimac is Luka, an impotent father struggling against all the tragedies that ravage his family: his son is called away for war, his wife runs off with a Hungarian musician, and he has a Muslim prisoner in his house. Left alone in Bosnia, Luka tries to close his eyes to the war, but the bombing attacks and the specter of war nearly intrude into his home. Of course this happens with a comic element, which Kusturica always uses.

The connection between football and the army is a well-expressed concept here, since, at the time, people who played in football clubs were automatically exempt from the draft. So, lots of football players tried to be excused from combat to play football. Luka’s son, Milos, is an example of this situation which has occurred throughout the history of football.

Another well-conceived and shrewdly-developed attribute is Kusturica’s characteristic surrealism. The viewer is amazed to see, in the middle of the war, a broken-hearted donkey who cries and tries to commit suicide and an old man ripping down a football post and beating some football players with it.

This succeeds in being funny because it suits the film’s unusual and particular ambience, which carries that Kusturican bizarre feeling. At this point, the style is almost a unique genre created by the Serbian filmmaker.

In this portrayal of a clash of civilizations, it’s very interesting to see the way Kusturica developed the plot. Suddenly, former rival countries are sleeping in the same bed. Luka and Sabaha represent the orthodox Christian Serbs and the muslin Bosnians respectively, and they quickly show how easy it is to put their differences apart. The chemistry of the unlikely couple is very strong and they provide some of the most beautiful scenes in the movie.

Emir Kusturica proves that love and war can coexist at the same time and place, as we can hear the sounds of bombs and gunfire just outside the house while we see kisses and tenderness in the bed. In a certain way, those two are living in a world understandable only to them. All the other people are simply on the wrong wavelength.

Once we consider the film’s music, in “Life is a Miracle” Emir abandons the Gypsy songs and festive music used in his previous works and instead embraces more melancholic, serene, and yet sometimes heartrending songs. As in the past, the soundtrack hits the mark perfectly! This new melodies are appropriate to this ‘90s Bosnia, which conforms more closely with the rest of Europe than it did in older times.

This politically incorrect film brings to mind the story about Stalin and his twenty four partridges, as told by Milan Kundera in “Festival of Insignificance.” At one point in this story, Kundera says that the world lost its sense of humor. In “Life is a Miracle”, no one can take a joke because they’ve lost their sense of humor too. I’m glad Kusturica didn’t lose his.

9. Promise Me This (2007)

Emir Kusturica likes to compare his cinema with a circus, where everybody can understand the events without needing to be from a certain region. He perfectly achieves that effect in “Promise Me This”, a true circus in film form. Unfortunately, the Serbian relies too heavily on exaggeration and slapstick, to the point that some roles come across more as mere clowns than as convincing characters.

The beginning of the story looks promising, but there isn’t enough sobriety in the plot, and those theatrical exaggerations spoil the movie to some degree. As we know, Emir is very attracted to musing on the past, and, once again, this is a story that sends the viewer to the director’s childhood.

In terms of traditional genres, “Promise Me This” is an adventure movie in which we root for the protagonist, and it carries some similarities to Aesop’s extremely metaphorical “The City Mouse and the Country Mouse.”

The country mouse here is Tsane, a kid who lives with his grandfather in the remote hills of Serbia. The boy is growing up and his grandfather is afraid of dying alone, so he sends Tsane to the city to sell a cow, buy a souvenir and a religious icon, and, last but not least, come back with a spouse.

Kusturica draws a cartoon version of those severe times, when there was great fear among the people due to the military events of the 20th century. Not only are the characters cartoonish, but the plot is as well. There’s a scene where the grandfather Zivojin cries as he listens to the Russian Anthem but his grandson is laughing as he enjoys the view of his teacher’s breasts.

The film also presents a very touching connection between those two characters, and it’s striking to see how they cry together and find comfort each other. The use of surrealism is evident too, with a crying painting of Saint Nicholas and a man from the circus flying over the city.

Kusturica maintains his distinct quality, for he certainly absorbs us for two hours in this funny, surreal and burlesque world. We can’t deny that merit. He does it in the same way Tim Burton does. Even if the movie is bad (and sometimes it’s really bad), Tim Burton always holds our eyes into the screen because of the visual aspect of his movies. Nevertheless, this is a bittersweet film.

The happily-ending stories of Kusturica have the weakness of identifying the good and the bad too overtly, which is rather tedious after a while. The good are poor and naïve and the bad always have guns and are dressed with black Motörhead shirts.

Another thing that looks very artificial is Tsane’s love at first sight and his friendship with a pair of guys who look like the duo from “Funny Games”: he sees Jasna, he falls in love; he meets two men and they easily become his best friends; etc.

In addition, the contrast between the suspicious city people and the goodness and blind trust of the village people is accomplished, showing some cynicism about the value of honor, which is no longer a reliable virtue nowadays. Even so, the kid likes to fulfill his promises.

If we consider the talent and sensibility that Kusturica shows on other occasions, then “Promise Me This” seems like a fairly disappointing and amateurish effort. Many of the adventures are rather childish, which is counterintuitive because, in the previous film, Kusturica showed precisely the opposite: maturity and confident knowledge of his craft. “Zavet” or “Promise Me This” depends a lot on the expectations of the spectator, and that’s a bad thing.

The ones who are expecting for a nuanced, artistic and subtle film like “Underground,” “When Father Was Away on Business” or “Arizona Dream” will have a massive disappointment. For those who expect some good laughs and lighthearted humor similar to “Black Cat, White Cat” or “Life is a Miracle,” with minimal concern for production and realism, this film could be a really enjoyable pastime. All the ingredients are there, but the recipe is different.

10. Maradona by Kusturica (2008)

This was Kusturica’s debut in the fertile world of documentaries, but this is more a tribute to and deification of Maradona than a relevant documentary about his life. As proof of this, the film opens with a Baudelaire quote: “God is the only being who, in order to reign, doesn’t even need to exist.”

The film doesn’t tell us much that really matters, instead focusing on gossip about the personal life of Diego and his drug abuse (which is not quite explored), while his way of playing football, his dreams and desires, or details about his career are neglected. I don’t know if anyone wants to hear Maradona singing and talking about his political views, considering that he was a real football god. But, oddly, football is not the major topic here.

Kusturica introduces himself as the “Maradona of Cinema” and associates “El Diez” with some of his movies in an interesting metaphorical exercise. He also compares Maradona’s challenges in football with class struggles or with the tension between USA and Latin American countries, which is predictable due to Kusturica’s and Maradona’s political views. This lends a certain Robin Wood feeling to the scene.

Kusturica himself provides the narration of the “documentary” with some poetic, admiring and very cliché speech, which abounds in quotes by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Jorge Luis Borges, Latin American writers. Kusturica abandoned the energy of his previous works because this is a very slow-paced presentation of a life story.

When Kusturica talks about Diego Maradona, it looks as if there’s nothing to tell, so all the speech and images are about the superficial aspect of the Argentinean former footballer.

The meetings between Kusturica and Maradó are supposed to look natural and spontaneous, but they fail in this regard. The viewer can easily tell that it is all staged, so it simply isn’t enjoyable or interesting to watch. Not even Kusturica, who can always show the beautiful side of things, can save this piece of mediocrity.

The Serbian confesses that he wanted to create the best documentary about Diego that was ever made, but this might be the absolute piece every filmed about “El Pibe de Oro.” It certainly is the worst film of Kusturica’s entire career. There’s also an exhibitionist segment about Kusturica, who here seems to exclaim “look at me, I’m great too!”

Strange though it may be, some of the things that the Serbian most harshly criticizes are present in this “documentary”: cheap appeals to popularity, superficial entertainment, and an egotistical perspective. This “documentary” doesn’t talk about the talent of Maradona and Emir – greats of football and cinema – but instead shows their weaknesses.

Emir Kusturica says that in the beginning they didn’t knew who Maradona was and, in the end, they still in the same place. This is precisely what this “documentary” does wrong: it fails to add anything pertinent or new. This is a film for those who know very little about Diego Armando Maradona and want to learn the basic, simple facts of who he was, what he did, and the problems he had in his personal life.

For those who really love Maradona and know lots of things about him, the film is very painful and boring because it doesn’t pay attention to the subtle details or the important things about Diego’s life.

For example, the film does not explore the beauty of his football playing, his Midas touch in Napoli where he triumphed with an underdog team, his dreams, childhood desires, or the extremely interesting conflicts with defenders such as Andoni Goikoetxea, the Butcher of Bilbao, known for causing several injuries to Maradona when the Argentinean was playing for Barcelona. The films pays its tribute, but the results is just that: a tribute and nothing more.

Author: Pedro Bento

You must be logged in to post a comment Login