The artist shapes the material to represent a wider reality in which the spirit dwells. In order to achieve this, is it possible to rely on a small inconspicuous object from everyday life?

Günther Uecker is a member of the post-war generation of artists. Born in the former German Democratic Republic in 1930, Uecker began his studies during Soc Realism. Having been influenced by the work of Kasimir Malevich (Казимир Малевич), who exhibited his paintings in Germany in 1926, he fled from East Berlin to Dusseldorf in 1953, in order to continue his education at the Art Academy. It seems that apart from the geometric purity of Malevich’s abstract world, representing incomprehensible metaphysical essence, the energy embedded in his works of art has also made a lasting impression on Uecker.

In Düsseldorf Uecker meets the turmoil of the era. Searching for his own expression in the culture marked by suppressed guilt, Uecker applies a generally accepted recipe – oblivion. An attempt to free his consciousness from the past, to live in the moment and for the moment, guides him from the practice of Buddhism and Taoism to Islam. Gregorian chanting is another way to make your mind susceptible to new experiences by ritual repetition. Such cultural climate contributed to the success of the Yves Klein’s Blue Monochromes exhibition in Dusseldorf in 1957. Sky blue or ocean blue monochrome canvases could be associated with emptiness or a new beginning. Yves-Monochrome, who married Uecker’s sister a few years later, became a friend, a mentor and a role model. It takes a little bit more time for a disciple to successfully incorporate the experiences of a teacher in his own work. Uecker’s practice of that time includes manual processing of thick layers of paint, as well as the setting of everyday objects on the canvas.

Finally, due to a twist of fate or just accidentally, it is the nail that appears in the picture. This tiny object made of steel from this moment on becomes an obsession. This revelation fundamentally changes first the philosophical orientation and then the artistic practice. The great theme of death joins the former interplay of life and art. With the force of repressed emotions, all of a sudden, neglected passion, suffering and pain are all brought to the surface. Uecker is ready to cope with reality. The insight roars:

“The post-war generation is becoming the pre-war generation.”

There is no denying, no erasing, no fresh start, it is time to embrace “the dark side”, to transform it and display it. Uecker’s catharsis will become the collective one.

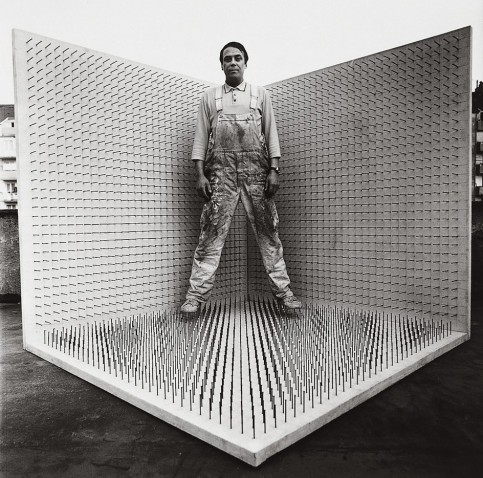

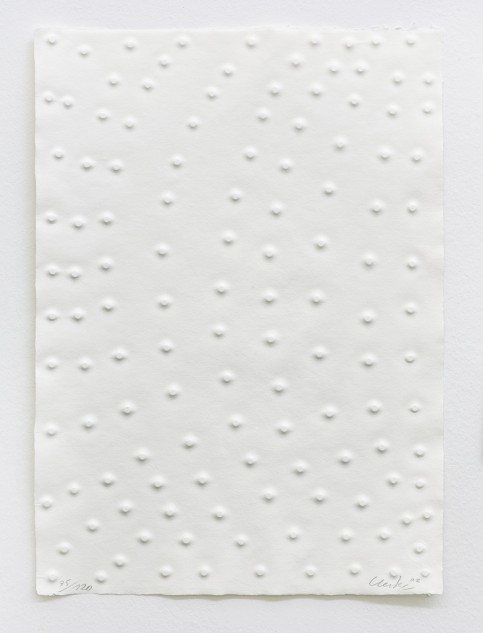

Initially, some kind of support is required. How to organize a new pictorial material? How to make it sing? How to lay bare its secrets? The starting point is geometry. The columns and rows of upright riveted nails are the echo of abstract purity. This deceitful harmony is further complemented by colour, mostly white, that covers both the nails and the surface – the influence of monochrome poetics. Klein’s work is only a support, a base from which Uecker will sail away into his own odyssey. Apart from many similarities, the differences are far more noticeable. Like Klein, Uecker feels a strong physical connection with his art; he feels that his physical strength and the way in which he moves greatly affect the object of artistic fixation, as well as the final results. Unlike the teacher who, during his anthropometry sessions, appears in front of the chamber string orchestra in an indispensable suit and a bow tie, Uecker wears dirty overalls in his photographs. His destiny is tied to the fate of those who work, suffer and get hurt. His brush is a hammer.

Solid structural organization, as well as the white colour in his works of art, led to the fact that Uecker exhibited together with two artists of seemingly similar orientation in 1958. Heinz Mack and Otto Piene are the founders of the Zero group, which Uecker formally joined in 1961. It seems strange that someone who has already found a way out of the post-war dilemma, returns to the beginning. The Zero group is a kind of opposition to the Art Informel movements such as Abstract Expressionism in America and the European Tachism, in which artists release their own insecurity, despair and the revolt of civilization through the pictorial material.

The intention of the group was noble – to revive the broken links between the alienated artist and society; to start from zero, putting aside disturbing content of which Uecker had become painfully aware. Apart from the common interest in Kinetic Art, the play of light and shadows, the combination of sculptures and paintings, there was always a critical difference, lurking and growing over time. Despite renewed interest in creating impressionistic effects, which implies a certain amount of optimism, a powerful expressionistic feature is unstoppably growing in Uecker’s work; something wild and raw, but not less beautiful.

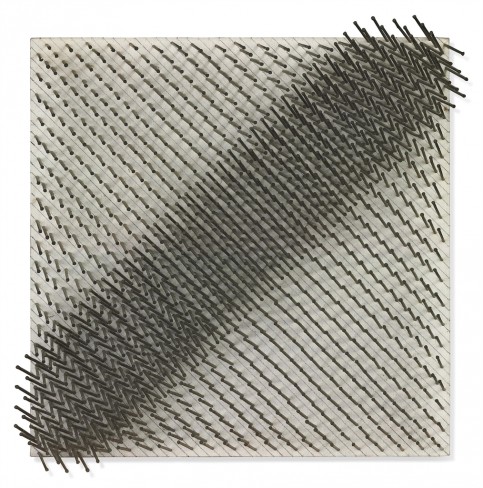

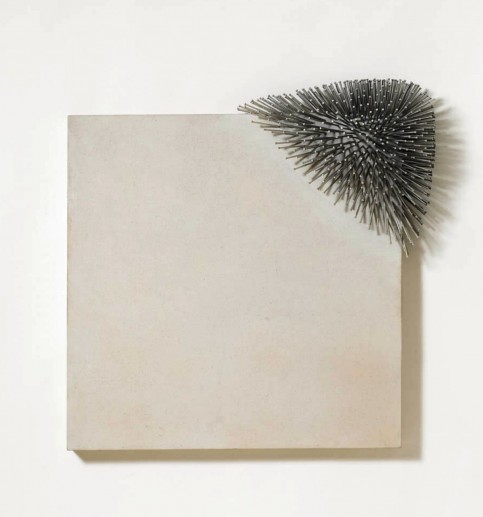

The military order of nails loses its rigid shape. With new confidence Uecker arranges the masses of riveted nails antisymmetrically. The point in which a steel blade sinks, is no longer a landmark in the fabric that conducts a controlled play of shadows. Some parts of his canvas or board are being attacked by the invasion of steel spikes, whereas the others are left entirely blank. The nail is more and more stripped down, without a layer of colour that masks its brutality. The infected, vulnerable, painful parts of the image are viciously exposed to the viewer.

The new organic structure further enhances the symbolism of suffering. The stab is ruthless. The inflicted wounds cannot be healed. At the same time, the nails are also a kind of protection, primordial defence mechanism, such as bristles, spines or thorns. The work of art “defends itself” with a harmless flat surface of the head of a pin. With each new breakthrough, Uecker conducts the cosmic energy necessary to deploy hundreds, even thousands of steel spikes. It is this voluntary suffering, this terrifying concentration, this exhaustive routine that injects the energy radiating from his works of art.

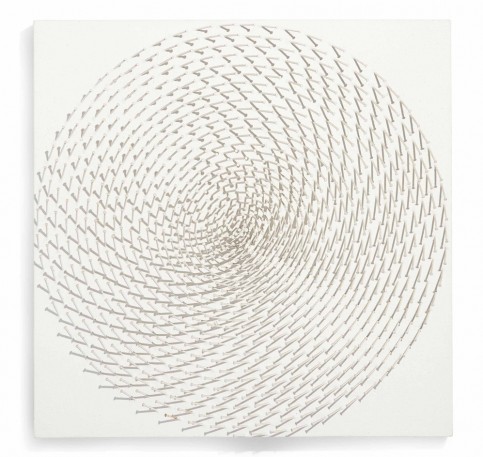

Sometimes, the upright nail bends. The aggressor falls as well as the victim. The waves of curved steel spikes represent a matrix or a torturing device? Across such a pattern, Uecker sets the clean white surface on which imprinted depressions remain, witnessing the pressure, as well as an ever fixed mark of a planned act. It is not always violence; Uecker often draws a parallel with work in the field, with ripe grain, with the circles of laid wheat. Even then, the circles resemble targets.

Cooperation with the Zero group didn’t last long. The artists split up in 1966, and by then Uecker had gained necessary confidence to ask questions, to tackle dilemmas, to be involved in the emerging problems of the modern world. The colonies of steel spikes “invade our everyday life”, bringing a feeling of unease into the comfort of consumerism. Everyday objects such as tables, chairs or TV sets, remain deprived of their basic purpose, but they ascend to a supreme reality, or rather returned into a context broader than sterile societal routine. After all, without the intervention of an artist, a nail is just a part of stale everyday life.

As an established artist, Uecker has ventured into installations, land art and happenings. Also, he has set the stage for Beethoven’s and Wagner’s operas with great success. Uecker participated in the exhibitions Documenta 3, 4 and 7 in Kassel (1964, 1968 and 1982) and Venice Biennale (1970). He was appointed as professor in 1976 at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, where he lectured until 1995. All this time he has been an active politically engaged artist worldwide. Serbian audience was able to get acquainted with his art in April 2001, when The Association of the Visual Artists of Serbia and The Goethe-Institut organized the exhibition “Exhausted Man: 14 quitened devices”, in The “Cvijeta Zuzoric” Art Pavilion. On that occasion, Uecker also translated and framed 120 verbs from the political language of hate of German extremists who called for deterrence of immigrants and foreigners in Berlin, in 1992.

Uecker once said:

”My failure is my art.”

Accordingly, art is a successful aesthetic shaping of societal failure. An artist nobly accepts that status. Does society accept the artist?

© ART HuNTER ::: Free

thinker and writer. Art

enthusiast and artist.

Mathematics professor.

Press corrector: Katarina Stanković, MA

You must be logged in to post a comment Login