The New Hollywood wave may be the most significant film movement in the history of American cinema. The classic era of Hollywood was built on vertical integration, meaning that the film studios controlled the production, distribution and exhibition of every movie they made, until the United States v Paramount Pictures Case forced the studios to end this monopoly of movies.

With the innovation of television only making things worse for the film industry, Hollywood was in need of something new and innovative, something different that could break the rules of everything they thought was essential to a critically successful and profitable movie.

The answer came from across the Atlantic Ocean, as the French New Wave took off internationally, it inspired an entire generation of filmmakers to put their own specific visions into practice. These two factors coincided so perfectly as the studios were willing to take risks on a new generation of filmmakers, right as a new generation of educated filmmakers were more eager than ever to enter the film industry.

Having been dominated by musicals and epics during the previous decade, this generation were focused on tackling more intimate and relevant themes, they were young, radical and everything Hollywood was looking for at the time as they sought to recapture the feel of European art house cinema. The directors in question were immensely talented individuals and instead of having their films constantly scrutinised by the studios, they were given more freedom to craft their own visionary ideas and concepts.

During this time, the director became the biggest star of the film, more than any actor producer or composer. Naturally a list attempting to narrow down the ten best is a difficult so to include some clarity, not only are these the ten best directors of the movement, they are the directors that embody the movement.

While juggernauts like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas also played a key role in the era of movies, this list will focus on those who personified the social commentary, realism and independence that defined the movement.

A few other directors worth mentioning (because there are so many) also include John Cassavetes, Hal Ashby, Peter Bogdonovich and Michael Cimino. But here are the final ten.

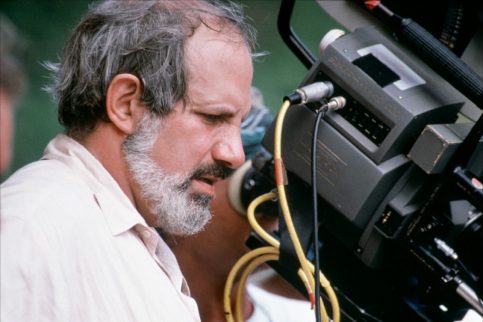

10. Brian De Palma

Most essential New Hollywood movie: Carrie (1976)

De Palma spent the late sixties crafting a small yet significant mark in the American independent scene with small hits such as Greetings and Hi Mom (both of which featured early roles for the up and coming Robert De Niro). In the next decade he quickly made a name for himself as a director of the psychological and supernatural thrillers. He put himself on the map as a new visionary with Sisters, a sort of homage to Hitchcock, yet one that was never afraid to rely on its own stylistics and themes when it needed to.

The nature in which De Palma draws suspense out of his direction and cinematography draws instant attention to his career and prominence. Perhaps his best known film Carrie gave him the position as an indisputable master of psychological thrills.

It was an observant examination of human character as well as a terrifyingly tense horror movie, becoming one of the few horror films to be nominated for multiple Academy Awards. Carrie used its suspense, suggestiveness and ambiguity to its full advantage as De Palma crafted a seminal horror film for generations to come, accompanied by a harrowing psychological portrait.

De Palma used the success of Carrie wisely as he experimented more in range as the movement drew on. His other projects included the science fiction thriller The Fury and though some felt De Palma was at risk of being a one trick pony he would go on to direct such masterpieces as Scarface and The Untouchables in the subsequent decade.

9. William Friedkin

Most essential New Hollywood movie: The French Connection (1971)

A man who was once reprimanded by Alfred Hitchcock for not wearing a tie while directing went on to forge one of the most varied and intense careers of the New Hollywood movement.

Friedkin’s movies shared a common theme of tension and terror, but they were all generated from a different genre and style, each one as innovative and unique as the last. He opened the decade with The French Connection, which was praised for its gritty realism and its use of a documentary style of filmmaking to capture a greater sense of realism that heightened its classic crime tropes to unprecedented levels.

His next film was the legendary horror masterpiece, The Exorcist. Friedkin utilised the most ferocious resources in special effects as he endured a tumultuous production to bring his film onto the big screen.

While renowned for its frequently graphic and disturbing content, Friedkin also used the story as a way to reflect themes of faith in the face of obstacles and tales of human interaction to underpin the films astonishing aesthetic and atmosphere of shock and nausea, but what makes The Exorcist incredible is its addition of hope to those emotions.

Friedkin’s sense of tension did not stop at horror either. In 1977 he reached into the realms of existentialism and brought forward a little film known as Sorcerer. Though it was a commercial failure (perhaps due to opening the same week as Star Wars) as well as being poorly received by critics it has later been regarded as an amazing thriller.

Friedkin’s directorial touches are perhaps most noticeable and admirable here as he employed an effective narrative, primeval stylistics and sustained sequences of suspense make it a masterclass of trepidation and peril.

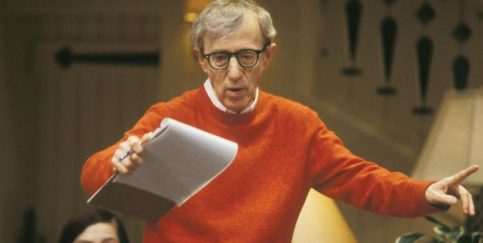

8. Woody Allen

Most essential New Hollywood movie: Annie Hall (1977)

It would be unfair to say that Woody Allen was completely unknown before the New Hollywood wave, having made a name for himself as a slapstick comedian and writer. But it was in the 1970s that Allen found his true voice, inspired by the European Art Cinema of the era he wrote, directed and starred in stories of endearing social relevance. They emphasised a fresh and new perspective on previously melodramatic stories of love, loss and life.

Annie Hall was a wonderfully intelligent and humorous film that never failed to pack a dramatic punch when it needed to, but at the same time it broke the fourth wall, played with the concepts of film itself and became a work of comedic genius. In the simplest terms it is a romantic comedy, but Annie Hall never feels limited by its genre and strived to be relevant to the era as well as timeless through an incorporation of both cultural references and pertinent themes.

Allen’s next film was his love letter to New York City, aptly titled Manhattan. As well as being superbly written with the same sharp and thematic style as Annie Hall but at the same time Manhattan retained a different sense of comedy through its own atmosphere, further romanticising the notions of love and relationships.

Yet it was Allen’s masterful direction that allowed the film to undercut these themes when it was required, not to make them seem over dramatic or sentimental. Allen was able to do this time and time again with his movies by taking big concepts and populating them with familiar and intimately shot humans in which we know the characters and feel their struggle even amid the ideologies of classic Hollywood.

7. Arthur Penn

Most essential New Hollywood movie: Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Having been persuaded to direct Bonnie and Clyde by its producer and lead Warren Beatty, Penn was able to pin down what was so compelling and emotive about this story of lover struck criminals.

It captured the attitude of the disaffected youth at the time, bringing out the film’s mass appeal to audiences of the time. As a result, it would become a rallying cry for the counterculture movement and attracted a great deal of attention, both good and bad.

Initial reviews were completely polarising, as many critics were disturbed by the films violent content matter, sometimes even in a comedic manner, and rapid shift between tones and style. Those who enjoyed the film praised it for the exact same reasons. It was Bonnie and Clyde that first sewed notions of love and violence so seamlessly together, that dared to sympathise with its protagonists despite their moral decadence.

Parallels between Penn’s movie and the artistic films from across the Atlantic were obvious. Its rapid fire style of editing, modern social relevance and humanity amid all the bloodshed made it a landmark in American cinema. Penn went on to direct a number of impressive films throughout the next decade with Alice’s Restaurant, Little Big Man and Night Moves but with Bonnie and Clyde alone he created a larger legacy than most directors do in their entire careers.

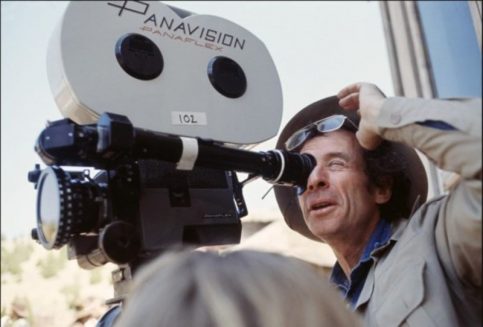

6. Mike Nichols

Most essential New Hollywood movie: The Graduate (1967)

Though many view Bonnie and Clyde as the first definitive film of New Hollywood, one can trace its origins back to the 1966 classic Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Beyond its thematic complexity and astonishing performances from Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, the film used profanity and sexual innuendo that was unheard of in cinema prior to its release, yet was still able to get a seal of approval from production codes of the time.

This was the final nail in the coffin for the more conservative rating systems in the film industry as the fact that the film had released proved that it was not even worth pretending that the code mattered any more.

The universal praise for the film earned its director Mike Nichols the title of ‘the new Orson Welles’. His next project was the iconic and youthfully charged film, The Graduate. It was a wonderfully subversive and relevant comedy, capturing a sense of free spirit and youthful alienation as it moves with a fast pace from one humorous situation to the next. The Graduate has something to say about everything from society to sexuality and once again appealed to the young audiences that were ready to take the film industry by storm.

Nichols developed a reputation as an auteur who worked closely and intimately with his actors to get the best performances he possibly could, whether it was the up and coming Dustin Hoffman to the experienced Elizabeth Taylor. He wanted to focus on the emotions that would drive his films, emphasising the human nature of cinema rather than pure spectacle.

5. Terrence Malick

Most essential New Hollywood movie: Badland (1973)

It would be unusual to give such high praise to a director who during this era, made just two films before taking an eighteen year hiatus from filmmaking, unless that director in question was Terrence Malick.

His 1973 debut Badlands was a richly textured film that can draw some comparisons with Bonnie and Clyde, a pair of young lovers commit a crime spree across the Midwest, blending comedy with violence in a contrasting and sometimes ironically juxtaposed ways. But there are key differences in how Malick embraced the grandeur of his script, examining the big picture of human life rather than intimate drama of individuals.

Badlands also substitutes the speed and intensity of Penn’s crime film for a frostier and remorseless tone. Most of this genius was attributed to Malick, with good reason. After his script for Deadhead Miles was deemed un-releasable by Paramount Pictures Malick made the decision to direct his own scripts, and in his own way without any interference from producers or studios, without fear or consideration for potential commercialisation. Malick perfectly encapsulates one of New Hollywood’s defining characteristics, the director is the artist of the portrait of film.

His second film, Days of Heaven was met with a less enthusiastic critical response upon its release. It would go on the be re-evaluated as a work of brilliance and a pioneering achievement in cinema. Like every movie he has made, Days of Heaven is visually stunning and deeply thought provoking. So with this respect and praise from Hollywood’s finest, what was Malcik’s next move? To not direct another film until 1999 of course.

4. Sam Peckinpah

Most essential New Hollywood movie: The Wild Bunch (1969)

Another key aspect of the movement was to put a revolutionist spin on existing genres. The genre that personified classic Hollywood more than any other may have been the western, films that usually consisted of morally straightforward, bloodless and simplistic conflicts (not always, but often). Sam Peckinpah brought forward one of the most violent, sadistic and human views of the west in cinema history with The Wild Bunch.

Peckinpah was best known for his for his visually innovative and explicit view of bloodshed and action, as he examined the conflict between ideals and values as well as the corruption of human society concerning violence. The Wild Bunch came at the perfect time to resonate so strongly with audiences dissatisfied with films that failed to show the consequences of violence following the Vietnam War.

Peckinpah continued that style with many of his subsequent films, crafting intelligent and controversial stories of suffering that remain provocative today. Straw Dogs in 1971 was a direct confrontation of savagery and prejudice that lay within humanity, then teamed up with Steve McQueen to make two more endearing and intense films Junior Bonner and The Getaway, both of which were successful and further advanced the crime-thriller genre as well as maintaining the themes that had established Peckinpah as such a unique voice of film.

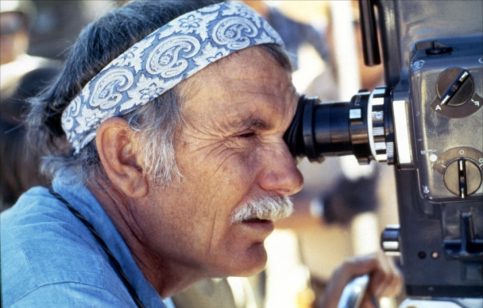

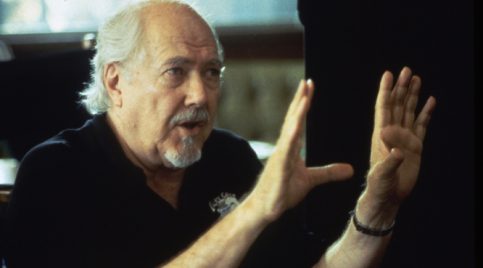

3. Robert Altman

Most essential New Hollywood movies: MASH (1970), McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), The Long Goodbye (1973), Nashville (1975)

You would be hard pressed to find a director with more variety and diversity within their body of work than Robert Altman. In the 1970s alone his films ranged from satire to western to musicals and all were deeply subversive, utterly compelling and completely magnificent.

MASH was a tumultuous production, especially for Altman with lead actors Elliot Gould and Donal Sutherland asking to have the director fired. The end result was a film that drew a clear parallel between its comedy and violence, portrayed soldiers as human beings in a way few had before and commendably bold in its criticism of the military.

Altman’s next film was a revisionist western McCabe and Mrs Miller. However that description may be improper as Altman himself has referred to the film as an ‘anti-western’ as it ignores and discards many classic tropes of the genre in favour of a plot driven by emotion and character as well as its brutal depiction of the American frontier. Altman wielded his camera in a fluid and unobstructed manner to capture the flowing nature of his actors and dialogue, clearly emphasising how this was a film of life and personality, not simple shootouts.

The 1970s also saw Altman direct The Long Goodbye, Thieves Like Us, but perhaps most importantly, Nashville. Like all of Altman’s movies it was a genre bender, it could be described as a musical but in broader terms it is an epic, a comedy, an utterly human drama.

It characterises the relationships and lives of two dozen people within the American folk music scene, and provides an almost complete summary of the 1970s, viewing those who loose and win, those who live and breathe within the world and without ever having to slow down the story for those unwilling to pay attention, Altman used his genius as a storyteller to capture a series of emotions that few have since been able to.

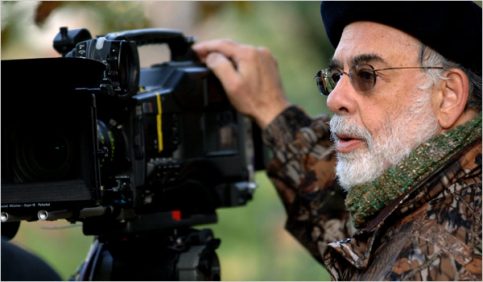

2. Francis Ford Coppola

Most essential New Hollywood movies: The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), The Conversation (1974), Apocalypse Now (1979)

Coppola won two Oscars in two years with his screenplays for The Rain People and Patton, what he directed next was The Godfather. That alone would cement any director’s place in cinema history, a work of absolute mastery. Coppola’s nuanced handling of the characters, in which they were portrayed as complex and humane individuals was an innovation at the time and used their struggle as a response to a corrupt society.

The sequel came in 1974, and elevated the saga to a Shakespearean level of tragedy as commentary of crime, corruption, the American dream and the struggle for power became a story of epic proportions, each one serving as a superb companion to the other, or stunning individuals.

The same year as Godfather Part 2, Coppola also released the widely acclaimed thriller The Conversation. The film was a bold statement of modern society perhaps more than any other Coppola film, and one that only gains more relevance as time passes. It examines the place of technology within society and its paranoia concerning information and intelligence.

Though the film was produced before a certain decade defining event in politics and therefore was not associated with it in its conception, audiences obviously reacted strongly to the film as it poignancy was heightened by being released just a few months before the Watergate scandal.

But with the decade drawing to a close and the New Hollywood movement nearing the end of its run, Coppola had one more masterpiece to make. Apocalypse Now, perhaps the greatest war movie ever made. Coppola used his twisted characters and environment to fully capture the madness and chaos of the Vietnam War. The film was about witnessing both the war itself and the effect it had on the participants, reaching into the darkest parts of the human soul as it becomes primal, selfish and arbitrary.

It was a descent into hell and insanity, with such a troubled production some question if the film permanently effected Coppola’s own mentality as a filmmaker. Regardless though, the end result was beyond words and essentially marked the end of the New Hollywood era, one of the most radical, innovative and experimental ages in film history.

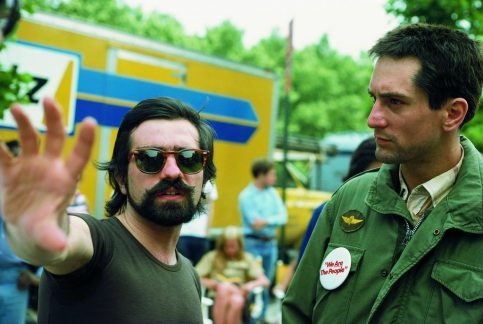

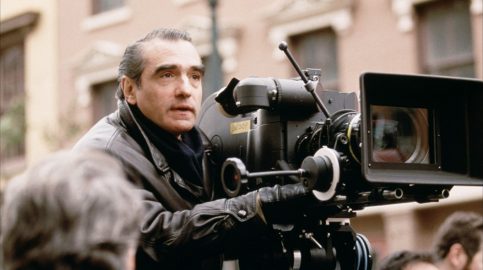

1. Martin Scorsese

Most essential New Hollywood movies: Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980)

If there is any director’s name that has permeated the last five decades of cinema to such an extent, it is Martin Scorsese, from his early hits of the New Hollywood era, to Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Departed and The Wolf of Wall Street, every decade since the 1970s has had a truly great Scorsese movie. His themes span from identity and isolation to conflict and redemption.

His first major success was 1973’s Mean Streets that encapsulated everything that the New Hollywood movement would be later praised for. It was personal, bold, gritty and realistic and was completely innovative in terms of its acting and direction. The rapid pace of its editing matched the unrestrained power of the movie and was just one of the factors that made it utterly enthralling.

What followed was Taxi Driver, one of the most unflinching, brutal and humane examinations of a character in film history. It established Scorsese as a giant in the directing world through its complex camera movements and cinematography. Like Mean Streets, it was also deeply personal as the film lives and dies through the perspective of Travis, we view New York through his ideologies and his isolation from the rest of its inhabitants. The fact that Travis is a veteran of Vietnam only made his psychological analysis more relevant.

Not only did Taxi Driver create a story of intimacy and relevance, it used the few moments it had to make a statement on society in general, its moral depravity and corruption, the injustice and social turmoil of the era. It is all through the eyes of one man’s struggle to cope with this society, his failure to simply incorporate himself with the current world and forget the horrors of his past. The psychosis of Travis represented the psychosis of an entire nation, and spoke directly to them.

Joshua Price

You must be logged in to post a comment Login