“Rashomon” is one of Akira Kurosawa’s most famous films, and is now considered one of the greatest films ever made. It is a very significant production for the Japanese movie industry since it marked its entrance to the world stage, a move that proved the prowess of Japanese cinema in the best way possible. “Rashomon” went on to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951, and an Honorary Academy Award at the 24th Academy Awards in 1952, among a plethora of other awards.

The film’s success in Japan was also significant, even in financial terms. It was given a Hollywood-like premiere at the Imperial Theater in Tokyo, then considered the best theater in the country, and despite its experimental and intellectual orientation, it earned large box office receipts all over the country. Long before it won the Golden Lion, it had won back its production costs, and theater managers considered it one of the greatest commercial hits of 1950. The same applied to the production company, Daiei.

Furthermore, it is considered one of the most influential films of all time, both in terms of technique and aesthetics, as it also established Kurosawa as one of the masters of world cinema. Here are five reasons why. Please note that the article contains many spoilers.

1. Great adaptation of a masterful novel

Although the movie borrows the title and setting from Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story “Rashomon”, it is actually based on another one of his works, the short story “In a Grove”, which provides the characters and plot. This novella is considered one of Akutagawa’s (who is regarded as the “father of the Japanese short story”) most iconic work, since it presents a combination of an early modernist style through the search for identity, and themes from classic Japanese literature, with the presence of samurais being the most obvious.

Kurosawa stayed very close to the story’s presentation, although he did not follow it to its fullest. In that fashion, a woodcutter and a priest find solace from the rain under the Rashomon gate and soon after, another passerby joins them. Waiting for the hurricane to pass, they busy themselves by discussing a heinous crime that occurred in the nearby forest, where a samurai was tortured to death and his wife was raped. The main suspect is a notorious bandit and the two of them were witnesses on the court.

The three men try to reach the truth, using their memories of the testimonies of the bandit, the wife, the samurai’s deceased spirit through a medium, and the woodcutter. Through these contradicting stories, Kurosawa presents a study of the human psyche, which eventually leads even the priest to doubt his faith in humanity. The finale, however, gives him hope again.

In explaining the script he wrote with Hashimoto Shinobu, Kurosawa said: “Human beings are unable to be honest with themselves about themselves. Even the character who dies cannot give up his lies when he speaks to the living through a medium. Egoism is a sin the human being carries with him. This film is like a strange picture scroll that is unrolled and displayed by the ego. Some say they can’t understand this script at all, but that is because the human heart itself is impossible to understand.”

In this fashion, Kurosawa set the humanistic and relative reality concepts that are the most dominant in the film.

2. Direction that works on many levels, with an elaborateness that changed the medium

“Rashomon” is a truly unique film, particularly due to Kurosawa’s direction. Starting with the narrative, Kurosawa presents a nonlinear puzzle, which presents conflicting takes on the same story. However, the element that makes a difference is that the audience never actually learns the truth, neither about the actual event nor the court’s decision.

The only thing provided is a sense of hope for humanity. In that fashion, Kurosawa stresses the impact World War II had on Japan, since the country was stripped of any cultural identity provided by their presumed military excellence and samurai principles. The ending of the film also suggests the same for Japan, as it provides a sense of hope through the fate of the abandoned baby.

However, the film’s most impressive quality lies with the concept of truth in connection to human nature. As the multiple narrations contradict each other, all of the individuals become untrustworthy, even the one who is already dead, and the woodcutter, who emerges as the “good guy” at the end of the film.

This reality, where everyone lies, either significantly or not, is presented through the details of the case. The way the samurai died, the wife’s attitude toward the two men, the missing dagger, and a number of other elements are all loose ends. The woodcutter may be kind, but the degree to which he becomes believable depends on the viewer, particularly after the third man in the gate confronts him for what he did with the knife.

The uncertainty of the events comes in direct contradiction with the perception that film, as a medium, is truth itself, since image coincides with fact. Jean-Luc Godard in “Le Petit Soldat” remarked that “cinema is truth twenty-four times a second.” However, a decade before, Kurosawa contradicted this statement with “Rashomon”, in a film where the camera seems to lie constantly. At the same time, through this technique, Kurosawa makes the audience a part of the truth, as each viewer can decide for himself which version he will adopt.

On a final level, Kurosawa also deals with the issue of honor, a concept that seems to be far more important than truth for the protagonists. This becomes obvious from the story each one presents, as they try to shape the events in order to avoid losing honor.

In that fashion, Tajomaru is infuriated when it is suggested that he has fallen from his horse, and tries to exemplify his abilities in battle. The wife is humiliated to the point that she cannot live in a world where even her husband feels contempt for her, as she identifies the lack of honor with shame.

The samurai focuses on personal honor, and according to him, his wife totally lacks it, while the bandit seems to have a measure of it. Lastly, even the woodcutter shapes the event in order to avoid revealing the fact that he has stolen the knife, as he does not want to be perceived as a dishonorable bandit.

3. Cinematography influenced from silent films, additionally giving meaning to each scene

With this film, Kurosawa actually wanted to make a tribute to silent films, and as silence takes over large parts of the movie, the focus on cinematography is even greater than usual. This trait is particularly evident in the scenes where the bandit, the samurai, and his wife are present. Kazuo Miyagawa, a legend in the Japanese industry through his collaboration with Kenji Mizoguchi, presents the theme of the same story through different perspectives, in outstanding fashion.

The framing, particularly of the three characters, is quite impressive, with Miyagawa using triangular compositions, with the one who speaks shot in close-up in order to give emphasis. As he uses dolly shots and pans, his camera moves perpetually, giving a sense of continuity in every scene.

Furthermore, his visual style gives meaning to each sequence. Take, for example, the scenes in the court. The setting looks extremely pure, in an open and well-lighted space where even the sand seems to be smooth, as this is a place where justice rules. On the contrary, the scenes in the forest are filled with shadows, and even the small amounts of light find it difficult to pass through the thick branches. This depiction symbolizes that the forest in the story is a place of lawlessness.

Even the impressive depiction of rain in the scenes occurring in the gate has its own meaning, as it represents the distortion of truth and the confusion shared by the priest and the woodcutter. As the woodcutter decides to take the baby to his house, which represents the future, the storm breaks. The same applies to the two characters. The priest has his faith in mankind restored and the woodcutter proves that he is actually a good person.

4. The use of natural light as exemplified in the scene in the woods

In a flashback that presents the case from the woodcutter’s point of view, the protagonist enters and walks through the woods carrying an axe. The 16 shots that make the scene show both the woodcutter and the sun through dense trees.

In the first aspect, his movement is depicted as both from left to right and right to left. This tactic is a metaphor for the case the film deals with, where nothing is predetermined and certain. As the woodcutter’s movement differs according to the point of view, the same applies to the case.

The second aspect, the shooting of the sun, was considered taboo up to that point, and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa is credited with the “first” use of the effect. The sun is shown through thick branches, with the camera turned upside down. The way the sun is depicted is as obscure as the way truth is presented in the film.

5. Acting in the style of silent movies

Since Kurosawa did not search for realism in the acting, and in accordance to the style of silent films, the majority of the cast gave overdramatized performances where they use their face, gestures, and eyes to express their feelings and thoughts, instead of words.

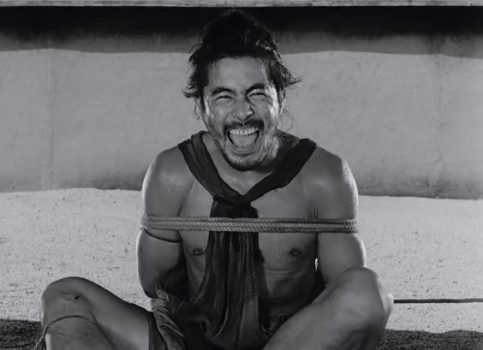

This trait becomes particularly visible in the cases of Toshiro Mifune, who plays the bandit, and Machiko Kyo, who plays the wife. Both of them act in a fashion that includes intensely expressive facial expressions, exaggerated laughs (usually in order to mock), and grandiose gestures. Kichijiro Ueda, who plays the commoner under the gate, also acts in the same fashion, with this trait being particularly evident during the last sequence.

On the other hand, although equally laconic, Takashi Shimura’s acting, who plays the woodcutter, is rather restrained, and emits the dignity that made him one of the most significant Japanese actors of all time.

Panos Kotzathanasis

You must be logged in to post a comment Login