Reputation and reception

James Joyce‘s Ulysses (1922) may be more talked about than read. It occupies an intimidating position within the literary canon as a byword for experimental modernism. Joyce helped to forge its reputation, mischievously claiming ‘I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality’.[1] Even Virginia Woolf, reading shortly after publication, found Ulysses a struggle, dismissing it as ‘diffuse’, ‘brackish’ and ‘pretentious’.[2] Prestige is evident in its perennial placing in lists of ‘Great Books’, and echoed in its value to collectors.[3] In 2009, a first edition sold at auction for £275,000, the highest sum ever achieved for a 20th-century novel.[4] Yet its reputation for difficulty masks the extent to which Ulysses is warm, welcoming and witty, granting a uniquely intimate perspective on what it is to be human.

Classical learning and popular culture

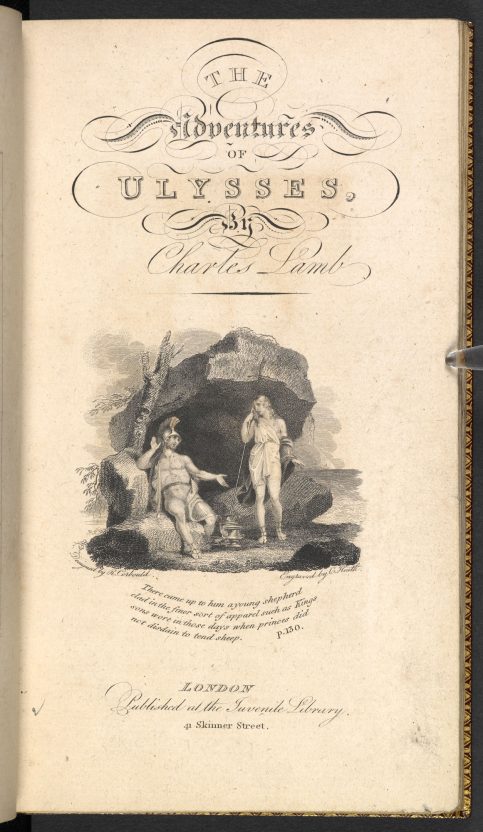

Ulysses is ostensibly a modern reworking of The Odyssey. Its 18 chapters were each named after an episode of Homer’s epic, and Joyce’s first critics made much of this tribute to shield him from the charge of obscenity. But Joyce’s appropriation of classical heritage is loose and irreverent. Joyce’s Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, is a middle-aged advertising salesman, whose wanderings are not across the world during many years, but around Dublin over the course of one day, 16 June 1904. Bathos is an essential part of Ulysses‘s comic treatment of its own cultural ambitions. Leopold Bloom’s first contact with the classical world comes in the fourth chapter, ‘Calypso’. Attempting to explain the term ‘metempsychosis’ to his wife Molly, he gestures towards a picture, The Bath of the Nymph, framed above the marital bed. The title suggests Greek legend, but the image is plainly titillating – and Bloom recalls it was ‘Given away with the Easter number of Photo Bits: splendid masterpiece in art colours’. Molly has read the term ‘metempsychosis’ in a popular novel – the sensational circus romance Ruby, Pride of the Ring – and Bloom endeavours to explicate ‘the ancient Greeks’ through reference to a promotional souvenir from a notorious soft-core men’s magazine. Later in ‘Lestrygonians’, Bloom wonders whether Greek goddesses have anuses, and, in ‘Scylla and Charybdis’, Buck Mulligan reports he has seen Bloom peering furtively at the private parts of Greek statues to check. Such moments summarise how Ulysses persistently entangles the high and the low, taking Homer as a frame for the shape of the novel, but embedding classical allusions within the fabric of throwaway popular culture or bawdy jokes. Homeric erudition is counterbalanced by rich references to sexy films shown on ‘What the Butler Saw’ peephole machines, or the music-hall song ‘Those Lovely Seaside Girls’, or an advertising jingle for ‘Plumtree’s Potted Meat’. Joyce’s canvas is not the mythic past, but the vibrant contemporary life of the modern city.

Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom: character and plot

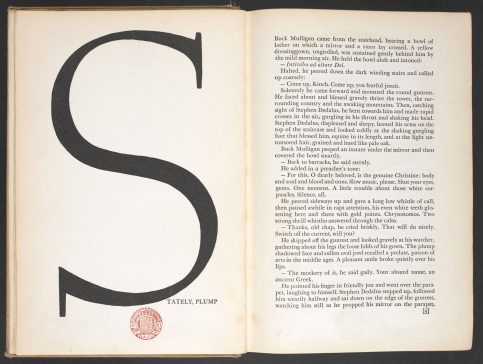

Leopold Bloom is Ulysses‘s central character, and the majority of the novel follows his perambulations around Dublin during the course of one day. But Joyce begins not with Bloom but with Stephen Dedalus, the ambiguously autobiographical protagonist of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). Some months after the close of A Portrait, Stephen Dedalus together with two friends Buck Mulligan and the Englishman Haines are having breakfast in their lodgings, a Martello tower on the Dublin coast which Mulligan has rented from the British government. Haines asks Stephen to explain his theory of Shakespeare, and readers familiar with the undergraduate Stephen from the fifth chapter of A Portrait – callow and prone to delivering his aesthetic theories with ponderous seriousness – may find their hearts sinking. However, Mulligan, capering in a silk dressing gown of jester’s yellow, is quick to protest: ‘I’m not equal to Thomas Aquinas and the fiftyfive reasons he has made out to prop it up. Wait til I have a few pints in me first … The sacred pint alone can unbind the tongue of Dedalus’ (ch. 1). Mischievous and mercurial, Mulligan summarises the way Ulysses punctures highbrow seriousness.

To Stephen Dedalus belong the first three chapters, the novel’s ‘Telemachiad’. Stephen, like Telemachus of Homer’s Odyssey, is the homebound son awaiting reunion with his wandering father. Odysseus’s role is granted not to Stephen’s real father Simon, a brilliant cameo of feckless charm, but, symbolically, to Leopold Bloom, who Stephen will eventually encounter in the closing hours of June 16th, after several near misses. Chapter four, ‘Calypso’, begins the day again with Bloom, and the shift precipitates readers from erudition to the everyday. Bloom is first encountered setting a kettle to boil, talking to his cat, and contemplating breakfast: ‘Kidneys were in his mind as he moved about the kitchen softly’ (ch. 4). His appearance heralds perhaps the most beguiling achievement of Ulysses: its probing of the extraordinary in ordinary daily life.

Bloom’s kitchen – shabby, functional, domestic – is a typical setting for this epic of the commonplace. It is the starting point of a day which will traverse the unremarkable city streets as Bloom runs errands: buying lemon soap from a chemist, attending a funeral, placing an advertisement in a newspaper, collecting a letter from a post office, ordering a sandwich in a pub, checking a reference in a library, eating dinner in a saloon bar, meeting an acquaintance by appointment in another pub, going for a walk by the sea-shore, calling in at a maternity hospital to ask after a friend in labour, visiting a brothel only to make his excuses and leave, having a cup of coffee in a late-night cabman’s shelter. These actions form the skeleton of the novel’s plot, but many of the pleasures of reading Ulysses arise from Bloom’s internal musings as he performs them.

Bloom the anti-hero

Leopold Bloom is deliberately anti-heroic. His profession is both new and uncertain. An advertising canvasser, he solicits commissions from small businesses, designs imagery and copy and negotiates its placing in Dublin newspapers. He is married to the glamorous Molly, an amateur opera singer of some local reputation – yet a letter from her lecherous manager Blazes Boylan arrives on the morning of the 16th, confirming an appointment with her that afternoon, and underlining to Bloom the inevitability of her infidelity. Meanwhile, he is involved in an adventure of his own – a perilous virtual flirtation with Martha Clifford, a ‘smart lady typist’ (ch. 8) he has contacted through a small ad. Precariously employed and precariously married, he is also a precarious father. A letter from his 15-year-old daughter Milly reminds him of his other child, ‘poor little Rudy’ (ch. 4), the longed-for son who died shortly after birth. If Stephen Dedalus is a son without a satisfactory father, then Bloom is a father always aware of the loss of his son.

Bloom’s relationship to faith and fatherland is similarly unstable. His Odyssean journeyings are shadowed by the legend of the Wandering Jew, punished for taunting Jesus on his way to the Crucifixion by being cursed to wander the earth until the Second Coming. Bloom’s Jewish heritage marks him as dangerously different in an Ireland constrained by narrow definitions of nationhood and blighted by casual, often vitriolic, anti-Semitism. In the ‘Hades’ episode, Bloom is excluded from his fellow mourners’ easy camaraderie. ‘The Devil break the hasp of your back!’ remarks Simon Dedalus ‘mildly’ as the funeral cortege passes ‘A tall blackbearded figure’ identified as ‘Of the tribe of Reuben’ (ch. 6). Bloom’s painful attempts to make himself fit in by telling ‘an awfully good’ parable of Jewish meanness is snubbed, as ‘Martin Cunningham thwarted his speech rudely’, taking up the joke himself. In ‘Cyclops’, Bloom is challenged by the one-eyed and unnamed Citizen, a virulent nationalist who demands of Bloom ‘What is your nation if I may ask?’, and spits when Bloom responds ‘Ireland … I was born here. Ireland’ (ch. 12). Yet Bloom’s Jewishness, which in ‘Cyclops’ necessitates his hasty exit from Barney Kiernan’s pub, a biscuit tin flung in his wake, is an identity only partially inhabited. He has been baptised into the Christian faith on three different occasions, and breakfasts on a pork kidney fried in butter, breaking three kosher dietary rules against pork, offal and the mixing of meat with dairy. Bloom is an outsider, an exile who can never belong, neither in Ireland nor in his ancestral faith. His perambulations across Dublin during the novel’s course underline his status as a subject out of place.

A new interiority

One of Ulysses‘s many pleasures is the unprecedented insight it offers into its characters’ inner lives. In ‘Calypso’, Bloom affectionately returns his cat’s mewing with a conventional ‘Miaow!’, but Joyce, more accurately, gives the cat a succession of nuanced vocalisations: ‘Mrkgnao!’, ‘Mrkrgnao!’, ‘Gurrhr!’ (ch. 4). The detail is more than a brilliant feat of feline transcription. It indicates Joyce’s commitment to capturing the individual voices of his subjects, most centrally Bloom himself. Bloom’s consciousness is caught with eloquent brevity: ‘Why are their tongues so rough? To lap better, all porous holes. Nothing to eat? He glanced round him. No.’ (ch. 4)

Joyce intersperses a narrative (‘He glanced round him’) with Bloom’s own thoughts (‘To lap better, all porous holes’). Bloom’s characteristic telegraphese (the clipped language of telegrams) grants a new kind of access to his consciousness, allowing readers to follow the intimate trajectories of his thoughts, and to learn not just what he thinks but how.

Numerous literary styles

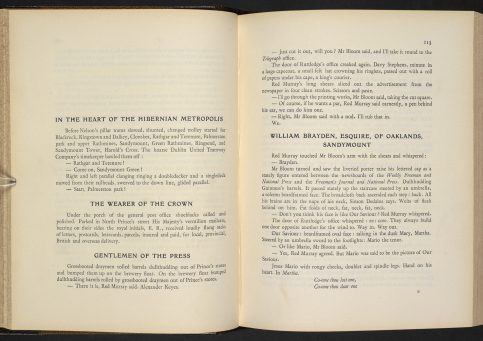

The intimacy of Ulysses‘s portrait of Bloom is achieved by the experimental nature of the novel’s many literary styles. The first chapter, ‘Telemachus’, initially resembles the free indirect discourse of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, but the novel soon gives way to a dazzling range of innovations. Bloom’s distinctive interior monologue, introduced in chapter four, is a dominant literary mode, in which Bloom’s fleeting thoughts, moment by moment, are counterpointed with terse description of his actions. But, as the novel continues, styles evolve to enhance content. Episode seven, ‘Aeolus’, takes place in the offices of The Freeman’s Journal, where Stephen and Bloom have business to transact. Appropriately, it is written in the journalese of a daily newspaper, where short paragraphs are divided by eye-catching headlines:

WE SEE THE CANVASSER AT WORK

Mr Bloom laid his cutting on Mr Nannetti’s desk.

– Excuse me, councillor, he said. This ad, you see. Keyes, you remember? (ch. 7)

Where ‘Aeolus’ is concerned with journalism, the ‘Sirens’ episode focusses on music. The beguiling song of Homer’s seductive mermaids are replaced by an impromptu sing-song performance by the regulars of the Ormond Quay saloon bar, but the musical theme informs the episode’s style, written in the loose form of a fugue, with an overture establishing the theme, variations and repetitions.

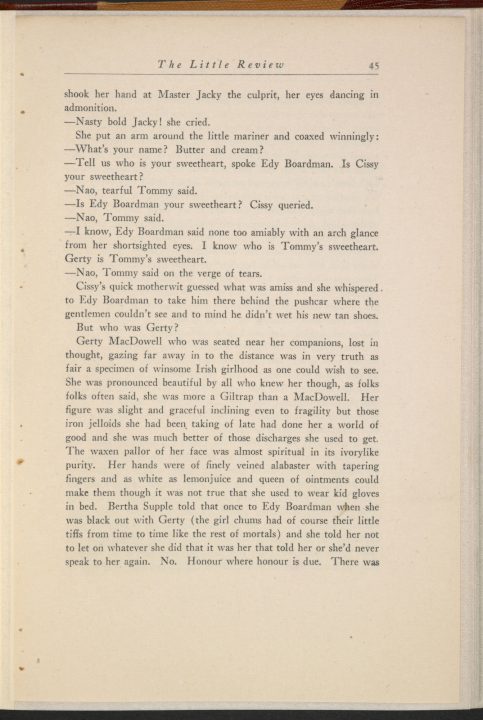

Styles echo substance, but they also enhance access to inner lives. The first half of the ‘Nausicaa’ episode describes 22-year-old Gerty MacDowell in the language of the romantic fiction she reads – exposing her imperfect masquerade as heroine, ‘as fair a specimen of winsome Irish girlhood as one could wish to see’ (ch. 13). ‘Circe’, written in the form of a hallucinatory play or film-script, reveals the phantasmagorical fears and fantasies besetting Bloom’s subconscious self. ‘Eumaeus’, the 16th episode, adopts the circumlocutary style Bloom himself might write: ‘they proceeded perforce in the direction of Amiens street railway terminus’ (ch. 16). The overloaded, elaborately ponderous writing seems teasingly designed to wear out the reader, encouraging vicarious participation in Bloom’s mental and physical fatigue. Exhaustion also inspires Ulysses’s final ‘Penelope’ episode, Molly Bloom’s sleepy small-hours soliloquy, in which everyday concerns mingle with erotic memories, and lovers substitute for one another. Joyce’s experiments with form and style create a fragmented montage from disparate modern modes of communication, while helping to create characters who become vividly real.

Too much information?

The intimacy of Joyce’s writing disconcerted Ulysses‘s first readers, even the most sympathetic. When Joyce sent the ‘Calypso’ episode to editor and mentor Ezra Pound for serial publication in the coterie New York magazine The Little Review, Pound was aghast at its ending. Feeling his bowels loosen, Bloom visits the outside privy, taking with him a copy of Tit-Bits, since ‘He liked to read at stool’ (ch. 4). Settling down, ‘He read on, seated calm above his own rising smell’. Joyce’s description of Bloom’s defecation was unprecedented. Pound was appalled: ‘Leave the stool to Geo. Robey!’ he advised.[5] George Robey, a popular music-hall comedian, specialised in risqué toilet humour which, to Pound, had no place in modernism.

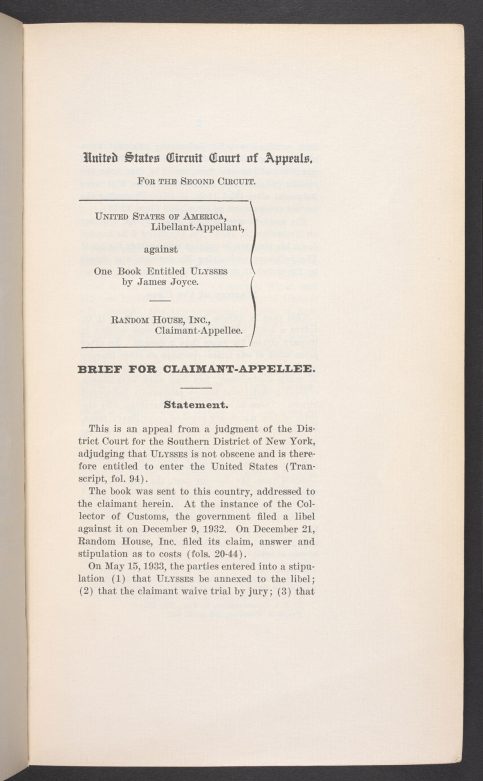

Pound’s shock anticipated the uproar Ulysses would later cause. The ‘Nausicaa’ episode, in which Bloom, watching Gerty MacDowell’s enticing leg-show on Sandymount Strand, masturbates to orgasm, assured the novel’s 1921 prohibition in the USA. Published in Paris by Shakespeare and Company in 1922, it soon became a byword for filth, most obviously manifest in Molly Bloom’s final erotic soliloquy. Banned in the UK until 1936, Ulysses was branded obscene. However, Pound, and Joyce’s later legal censors, missed the wider significance of the novel’s explicitness.

‘Obscene’ derives from the Greek for ‘off-stage’, and refers to material which should remain behind the curtain, beyond the limits of representation. For Joyce, nothing was off-limits. Following his characters into their most private moments, depicting them ‘at stool’, or, in Molly’s case, beginning to menstruate astride a chamber-pot, was part of a larger creative commitment to represent fully his characters and the experience of living in the modern world. Ulysses‘s central achievement is its humane dedication to recreating everyday life with intoxicating intimacy.

Footnotes

[1] Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 573.

[2] The Diary of Virginia Woolf, ed. by Anne Olivier Bell and Andrew McNeillie, 5 vols (London: Hogarth Press, 1977-84), II, pp. 199-200 (entry for 6 September 1922).

[3] Ranked 46 in The Guardian‘s ‘100 Best Novels’ (2014); ranked 1st in the “100 Best Novels” survey by the Modern Library Editorial Board of authors and critics.

[4] http://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/jun/04/ulysses-sells-record-price

[5] Paul Vanderham, James Joyce and Censorship (New York: NYU Press, 1998), p. 19.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login