Next year will be the 50th Anniversary of one of the greatest films ever to be put on the silver screen, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Made in 1968, Kubrick’s tour de force is an iconic piece of modern media art, with its immeasurable influence still being felt on contemporary directors and filmmaking ideologies even in the 21st Century.

With ground-breaking visuals, an instantly recognisable soundtrack and several avant-garde cinematic techniques, 2001 is a genuine masterpiece of cinema, and for that reason (as well as several others), is the greatest Science Fiction film of all time.

1. Subversion of Classical Cinematic Techniques

After dominating American silver screens for the previous four decades, the cinematic style of “Classical Hollywood” filmmaking was finally beginning to decline towards the end of the 1960s. Films such as Easy Rider (1969) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967) signalled the start of a new era, and with it came a complete reformation in the American approach to cinema.

Following along in this progressive movement, whilst also being completely unlike anything in Hollywood at the time, was 2001. Kubrick’s paragon is generally considered to be a part of the New Hollywood brand of filmmaking, however it is arguable that 2001 was still largely unmatched in America in its subversion, distortion and sometimes outright rejection of the previously indispensable cinematic rules and techniques that dominated Classical American cinema.

For example, the narrative logic of Classical Hollywood cinema would often follow the psychological processes of a single central protagonist, often attempting to reach a final goal or conclusion. This structure of a beginning-middle-end linear narrative, the norm at the time, is largely abandoned by 2001.

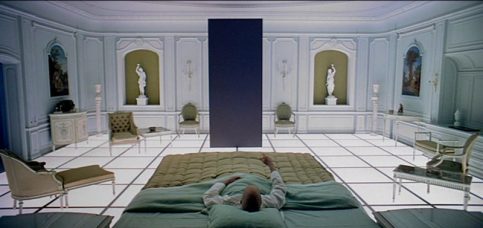

The only recurring “character” in the 3 main sections of the film – the enigmatic, other-worldly black Monolith – has no emotion, no action, and certainly no psychological process to follow. This not only means the classic “goal-orientated” narrative is deserted, but also that the audience cannot truly gain any emotional connection with any character, creating a distancing and meditative effect that allows the viewer to genuinely reflect on the film for themselves, rather than from the point of the view of a protagonist.

Furthermore, the use of cinematic time in 2001 is warped to a degree so extensive and far-reaching that the audience witnesses not just two, but three stages of human evolution in under two and a half hours. The film begins with primitive apes learning how to use bones as weapons, whilst the ending looks beyond the human race at a species even more advanced than ourselves – the “Starchild”.

In a single jump cut, Kubrick moves from an ape throwing a bone into the dry African sky to a Pan Am Spaceplane, moving through outer space millions of years later; possibly the most ambitious jump cut in cinema history. This ambition would have never occurred in Classical Hollywood, with continuous, linear and uniform timelines (flashbacks were occasional) being the standard.

There are several more examples of the ways that 2001 rejected the traditions of Hollywood filmmaking, and the ways in which Stanley Kubrick consistently used these subversions to the advantage of the feature. However, by the abandonment of two key classical cinematic rules, the logic of narrative and time in a film, it shows how far Kubrick was willing to go to achieve his vision, and – by the success of the film – how adroitly he executed it.

2. Strong Themes of Existentialism and Technology

Those who attempt to criticise Stanley Kubrick often argue that his films lack a genuine emotional depth, making his whole filmography appear cold and distant, regardless of technically proficiency. There may be some truth in this argument – from Spartacus onwards his films began to have an increasingly nihilistic view of the society around him – however in 2001, it must be stated that the film’s lack of emotion (or more accurately, lack of human emotion) is necessary for the rest of the films major themes to be fully explored by Kubrick.

From the moral dilemma of A Clockwork Orange to the duality of man in Full Metal Jacket, the philosophical beliefs of Kubrick, shown throughout his career, point towards the existentialist-nihilist end of the spectrum. This is presented consistently, and with great significance, throughout 2001.

The tenets of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, as well as his belief of the Ubermensch, can be recognised in the events concerning the Apes, Bowman and the Starchild – man’s final evolutionary step towards the “Supermen”. This development into higher life through Bowman’s own individual acts of will is strongly existentialist in its conception, giving meaning to his own life through the virtue of authenticity.

In addition to the possible philosophical connotations, the relationship between the human race and technology is one of the more obvious themes of 2001. The HAL 9000 Computer, an effectively perfect entity, is put at odds with Bowman and Poole (the human race) when it becomes aware of the true importance of the Discovery One’s mission to Jupiter.

This raises the question, can we really trust technology? Will technology, if sentient enough, sabotage the human race in pursuit of its own gain, just as HAL does? In the context of 1960s America where the global “Space Race” dominated the news, and even today with the development of robots and potential A.I., these questions remain totally and unequivocally relevant.

Nietzsche and technological progress are two of the many thematic influences on 2001, and also two of the most important. Through the rejection of emotion and character development, Kubrick allows these themes to be fully investigated, removing all ulterior motives from Bowman and HAL to reduce them right down to the basic existential human purpose; survival of the individual, and exceeding that, evolution.

3. Ground-breaking Special Effects

Special Effects (SFX) in 21st Century cinema, with the aid of CGI, have reached unprecedented levels of accuracy, detail and creative reverie. Jump back nearly 50 years, and the SFX team working on 2001 – including the acclaimed SFX supervisor Doug Trumbull – were making cinematic history as they put together what was then ground-breaking visuals, paired with unparalleled scientific accuracy.

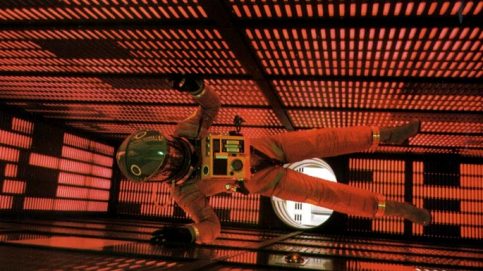

Trumbull, one of four SFX supervisors on the film, was responsible for the development of slit-scan photography on the set of 2001. Now fairly common in use, at the time it required a uniquely adapted custom built machine, and Trumbull’s utilisation of it resulted in one of the most iconic and essential scenes in the film; Kubrick’s transcendental “Stargate” sequence.

Slit-scan photography may have been the most truly original effect employed by Kubrick, Trumbull and Co., however many other SFX in 2001 are just as impressive in their ambition and scope. The rotating sets (Kubrick had a 30-short-ton Ferris Wheel made for $750,000), zero-gravity illusions and use of detailed miniature spacecraft models all contributed to the fantasy Science Fiction element of the space epic, aweing 1960s audiences in the reality of its magnitude.

Kubrick won his only Oscar for the Visual Effects of 2001, and deservedly so. The work of Trumbull and other SFX supervisors must also not go unmentioned in the legacy of the feature, with their contributions helping to create visuals that were unmatched in quality and originality at the time of the film’s release, and still stand up today as some of the best SFX in Science Fiction cinema history.

4. Bold and Challenging Ambiguity

Ambiguity in cinema, and art in general, can be both a blessing and a curse. Often in Hollywood and mainstream cinema, ambiguity is rejected in favour of literal narratives and themes, appealing to the masses and drawing in as large an audience as possible.

Although there is certainly nothing wrong with this, it is arguable that an element of ambiguity can allow individual viewers to interpret the work for themselves, therefore evoking a more genuine and personal emotional response to a film. This ambiguity, of course, can be taken too far – an incessantly idiosyncratic piece of art can be just as mind-numbing and ineffective as a completely literal one.

Kubrick plays this fine line between literality and idiosyncrasy perfectly in 2001. Linked together only by the constant recurrence of the perplexing black Monolith, the narrative of 2001 is certainly ambiguous, as are its characters. The four central parts of the piece – Dr. Floyd, Bowman, Poole and HAL – are barely characters in the classical sense.

There is almost no emotional connection between the four and the audience, with little being known about any of their backgrounds, opinions or personalities; the closest we get to any true emotion in 2001 is, perversely, from the HAL 9000 Computer, showing one of the most basic human facets – a fear of death.

This abandonment of the classical use of characters allows the viewer to meditatively explore the rest of films events for themselves, which in their own right are ambiguous and largely unexplained.

The “Stargate” sequence, Bowman’s final moments of life, the resulting Starchild – a 20 minute psychedelic rollercoaster with no dialogue, no emotion and no consistency in location or time. This bold conclusion from Kubrick leaves the audience suspended in a mixture of awe and thoughtfulness, pushing them further and further to think about the films meaning for themselves, rather than simply being told what to think.

Some may argue that 2001 is too ambiguous, making it difficult and even strenuous to watch. This may be true, but without films that challenge and provoke the viewer then we will be left with only literal art that does not truly question anything, and therefore answer nothing. This shows the importance of Kubrick’s unapologetic oracle, and the directorial skill it took to execute the work without completely alienating the mainstream.

5. Stanley Kubrick’s Magnum Opus

After becoming concerned with the increasing amount of crime in America, a 33 year old Stanley Kubrick moved to the county of Hertfordshire, Southern England in 1961. Despite being a world away from the shining stars and bright lights of Hollywood, Kubrick, from his Manor in the country, became one of the most respected and successful directors of the era.

A duo of comedies with the legendarily versatile Peter Sellers (Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964)) shot Kubrick into stardom, and by the late 1960s he was gifted with what all directors dream of – complete creative and artistic control, whilst also possessing the stature in the film industry for any feature to be commercially viable.

Kubrick – producing, co-writing and directing the film himself – took complete advantage of this freedom. A demanding perfectionist the vast majority of the time, this independence allowed Kubrick to fully exert the meticulousness of his unique directorial style, creating a work that was, at the time, completely unrivalled in its scientific realism, technological accuracy and special effects.

2001 also marked an artistic turning point for the still relatively young Kubrick – by 1968 he was still only 40, and still had over 30 years of his career ahead of him. Not only did the work venture into a completely new genre Kubrick had previously not employed, but it also marked his first experimentation with colour in film, which he uses with aplomb in the infamous “Stargate” sequence – “the ultimate trip”, indeed.

Furthermore, 2001 signalled the end of Orson Welles’ vast cinematic stature overshadowing Kubrick, with the former’s influence being felt immensely in the earlier stages of Kubrick’s career. Bill Krohn, a correspondent for Cahiers du Cinema, stated – “Nothing Kubrick did after 2001 resembles anything by Welles, because this is when Kubrick began making films that are like no films that had ever been seen, including his own”. This then, shows the utmost importance of 2001 to Kubrick and his legacy, and therefore to the whole of Cinema; with this epic achievement of grandeur and eloquence, Kubrick evolved into a cinematic giant on the level of Hitchcock, Chaplin and Welles.

In an oeuvre of impressive and highly influential filmmaking, 2001 stands above the rest in Kubrick’s filmography as a masterpiece of cinema, Science Fiction and modern media art. Elevating him from the shadow of Welles, 2001 truly etched the legacy of Kubrick into the very framework of cinema history, leaving arguably the greatest filmmaker, and greatest film, to ever be seen.

6. Predictions of Modern Technology

Nowadays, technology is generally taken for granted and accepted as the norm in the Western world. Smartphones, laptops and tablets are all the product of great scientific advancements in the last decade or so, with the expansion of technology still seeming potentially infinite in the dynamic marketplace of the 21st Century.

However, preceding this vehement acceleration in the development of modern technology, speculation of future computers and machinery was universal; and no more so than in the Science Fiction genre. Blade Runner and Back to the Future hypothesised flying cars, whilst I, Robot and A.I Artificial Intelligence (to which Kubrick contributed to greatly in its development) predicted the eventual creation of mentally “conscious” machines – AI.

Despite the once fantasy concept of Artificial Intelligence now potentially becoming reality, flying cars are still considerably far away from becoming commercially and environmentally viable. This makes the predictions of modern technology in 2001 all the more impressive – both Blade Runner and Back to the Future were made in the 1980s, and were substantially more farfetched than anything found in Kubrick’s work.

Not only was the technology in 2001 startlingly accurate and realistic, but also heavily influential on what we see today – Samsung once even argued in a lawsuit that Apple’s iPad was in fact based upon the Visual Tablets used by Bowman and Poole on the Discovery One. The audio-visual call between Dr. Floyd and his daughter greatly resembles the facets of FaceTime, whilst the eerily monotone voice of the HAL 9000 computer could even be labelled as an early vision of Apple’s built-in helping hand, Siri.

Made in 1968, nearly 50 years ago now, Kubrick’s (and his teams) predictions of modern technology are simply astounding in their precision, clarity and progressiveness. No Science Fiction film, or any film for that matter, has ever matched 2001 in its veracity of the distant future; and it could be quite possible that no film ever will again.

7. Iconic Soundtrack and Use of Music

After working with Hollywood composer Alex North on his two previous features, Spartacus and Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick commissioned his regular colleague to create a score to match the visual immensity of his upcoming work, 2001. Boldly however, Kubrick removed North’s compositions in the post-production process, replacing them with the epic classical pieces that the feature is now perpetually associated with. North’s unused score is nevertheless a strong effort and deserves its own individual recognition, however it is hard to argue with Kubrick’s final choice – a soundtrack that equals, if not exceeds, the quality of the visual and thematic action of 2001.

Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s seminal work of the same name, opens Kubrick’s feature in an image of pure majesty; the sun rising over the Earth and Moon, showing us the vastness of space and the insignificance of ourselves in the blackness of the Universe. Paired with Strauss’ eternally iconic tone poem of double basses, organs and trumpets, the scene becomes not just a great sequence in its own right but also a fitting introduction to the tone and vision of the film. Contemplation, spectacle and absolute possibility; both Strauss and Kubrick sought to elicit these responses from their respective audiences, together creating one of the most iconic and epic opening scenes in Cinema history.

Paul Thomas Anderson, a great contemporary American filmmaker in his own right, said of Kubrick; “It’s so hard to do anything that doesn’t owe some kind of debt to what Stanley Kubrick did with music in movies. Inevitably, you’re going to end up doing something that he’s probably already done before”. Many have attempted to imitate or parody 2001, but few will ever truly live up to the utter immensity of Strauss’ transcendent symphony, or how effectively Kubrick put it to use in his vast tale of galactic exploration.

8. Limitless Interpretations

Being one of the most famous films in cinema history, 2001 has had more than its fair share of critical and professional analysis. It’s purposeful ambiguity and open ended conclusion has resulted in almost limitless interpretations about its conception, influences and true meaning.

The whole piece can be taken from several angles; philosophically, theologically, as an allegory, or even as a postulation on the process of evolution. Since the existential philosophical viewpoint has already been discussed in this article, only the religious and allegorical exegesis will be focused upon in this point. Saying this, all of the themes interweave into one larger commentary regardless of how much you attempt to separate them, and, of course, there is no right or wrong – Kubrick himself encouraged speculation, and refused to offer an explanation of “what really happened”.

Theologically, it can be proposed that the narrative of the film itself is in fact a search for God, or the scientific equivalent of him. The possible purpose of the unexplained Monoliths can be likened to the purpose of Earth’s Western monotheistic prophets such as Muhammad, Jesus and Abraham; to spread the word of God and help us learn of his existence and truths. The Monoliths aid both the apes and Dr. Floyd, and eventually, when Bowman has reached the final Monolith on the outskirts of Jupiter, help him transform into the “Starchild”, reaching a heavenly status as he finally learns the truth of a higher being.

Alternatively, it can be argued that Bowman himself becomes a God, with Kubrick telling the audience that there is in fact no monotheistic God, but rather only a scientific definition of a higher being, and that this being is the next step in evolution past ourselves.

In addition to these theological assumptions, the whole feature can be seen as an allegory of the process of conception. The apes, being the most primitive, are seen as the birth of the human race, whilst Dr. Floyd, Poole and Bowman are seen as the representations of everyday human life. The “time warp” scene in which Bowman rapidly ages with no explanation has been interpreted to represent the ageing and death of the human race, shown by the birth of a completely new species; the infinitely more advanced “Starchild”.

Whether these interpretations are wholly accurate or inaccurate is truly unimportant. The significance of these several inferences is that 2001 is not telling the audience anything, but rather making them think for themselves and form their own opinions on God, existence, and human purpose. Kubrick harnesses ambiguity to thrust the viewer into challenging thought, resulting in one of the most speculated upon moral and thematic messages of 20th century modern media artwork.

9. Legacy and Influence on Filmmakers and Cinema

Even the (very) few who do not recognise 2001 as a masterpiece of cinema cannot deny its legacy and influence on several generations of filmmakers. Two of the most popular directors of the 70s and 80s, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, can be seen as having taken direct influence from 2001, both in its visuals and cinematic ambition.

Even further than this however, the ripples of the 2001 tidal wave can still be felt on modern cinema today, with established directors such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan citing it as an inspiration towards their own works – Nolan’s Interstellar, especially, can be seen as harking back to Kubrick’s magnum opus.

2001, simply from a visual point of view, clearly had great impact on the Sci-Fi genre as whole. With its ground-breaking special effects,

Kubrick and Trumbull showed that nothing was impossible to film; even zero gravity action, rotating surfaces and psychedelic space trips. The use of small scale models to capture the immensity of space is mirrored by Lucas in his Star Wars trilogy, and several other filmmakers harnessed this technique before the modern development of CGI.

This aesthetic influence is perhaps not as relevant as it was previously, with the technological developments of the digital age making models and slit-scan photography techniques effectively obsolete. Despite this, the influence of 2001 on Sci-Fi cinema is still immeasurable – before blockbuster hits such as Alien and ET, very few Science Fiction films were taken seriously, making them commercially inviable. 2001 was the first “serious” Sci-Fi film to be successful in the brutal market-place of cinema, therefore effectively establishing the “Sci-Fi Blockbuster” genre and influencing cinema as a whole to a fathomless extent.

Spielberg once labelled 2001 as the “Big Bang” of his generation, and this may potentially be the most important facet of Kubrick’s influence canon. Regardless of visual, thematic or even commercial influence, what 2001 truly encourages all filmmakers to do is to pursue their cinematic vision at all costs, to think independently and, most importantly, use cinema as a medium for intelligent and progressive thought – an invaluable message that will influence filmmakers of any age, skill or circumstance.

10. Transcendent of the Sci-Fi Genre

If 2001 was forcefully categorised into a single film type or genre, the answer would almost definitely be Science Fiction. Containing many Sci-Fi tropes, 2001 certainly uses several motifs of the genre. Travelling millions of miles through space, various different types of spacecraft, astronauts floating through space without the restraints of gravity – all of these images are perpetually attached to Science Fiction cinema, and rightly so. Why then, despite employing a range of classical genre elements, does 2001 feel like so much more than just a Science Fiction film?

A possible explanation is the high-brow themes and ideologies that diverge themselves in 2001, which, in the vast majority of other Science Fiction features, are largely avoided. Perhaps with the exception of Blade Runner, no other Sci-Fi blockbuster can claim to address existentialism, theology and the condition of the human purpose to such a complex, intellectual and elaborate degree; very few films at all can declare as much philosophical consciousness as 2001.

Another potential reason for 2001’s transcendent feel could be its immense influence on the entirety of cinema. Outside of just the Science Fiction genre, Kubrick’s space epic encourages freedom and individuality in cinema, as well as the benefits of using the facet of ambiguity in both the narrative and themes of a feature. By rejecting the classical cinematic style of 1920s and 30s Hollywood, Kubrick pushed the boundaries of mainstream cinema further than any director before him with 2001, taking full advantage of the creative freedom he had been gifted to bend the rules of cinema to his will, becoming a master of his craft in the process.

A third and final explanation could be the astounding longevity that 2001 possesses. Next year will be the film’s 50th Anniversary, yet the themes it addresses, its visuals and its set designs are still stunningly contemporary.

As long as cinema remains progressive and forward-thinking as an art form, 2001 will always be alongside it, endorsing modernity and dynamic thinking in film. Similar to the vast black Monolith, 2001 will tower over cinema for the eternity of the medium, helping it to evolve and progress regardless of any external factor; it has become an absolute constant in film, and a building block upon which modern cinema has been built.

These reasons, as well as many more, are all contributors to the transcendent, epic and superlative quality of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. There is not one overwhelming factor that places the work higher than the rest of Science Fiction cinema, but rather, a whole host of combining factors that work simultaneously to create what is a philosophical essay on human existence, an ambiguous exploration of possibility, a ground-breaking achievement in Sci-Fi cinematic visuals, a hugely influential piece of artwork, a Nietzsche inspired existentialist commentary; all of these ideals, and much more. The beauty of 2001 is that it can truly be whatever you want it to be, regardless of anybody else’s interpretations or viewpoints. Stanley Kubrick, a genius on a par with Welles and Hitchcock, knew this:

“The very meaninglessness of life forces man to create his own meaning.” – Stanley Kubrick, 1968

Source:

10 Reasons Why “2001: A Space Odyssey” Is The Greatest Sci-fi Movie of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment Login