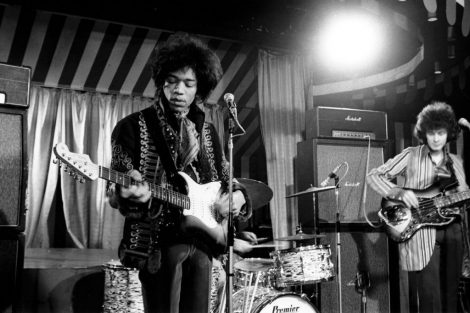

“We’ve been doing new tracks that are really fantastic and we’ve just been getting into them,” Jimi Hendrix told Rolling Stone in February 1968, right after he and the Experience had played San Francisco’s Fillmore West. “You have these songs in your mind. You want to hurry up and get back to the things you were doing in the studio, because that’s the way you gear your mind….We wanted to play [the Fillmore], quite naturally, but you’re thinking about all these tracks, which is completely different from what you’re doing now.”

No one knew it at the time, but the new tracks Hendrix was referring to — which he, bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell had been working on intermittently since the previous summer — would form the nucleus of Electric Ladyland, the sprawling double album that would finally see the light of day October 16th, 1968. The final studio album ever recorded by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and their only one to top the charts on both sides of the Atlantic, Electric Ladyland saw Hendrix moving light years beyond his two previous works, Are You Experienced?and Axis: Bold as Love, both of which had been released in 1967.

While the stomping “Crosstown Traffic” and the smoldering psych pop of “Burning of the Midnight Lamp” wouldn’t have sounded particularly out of place on either of those records, Electric Ladylandwas full of bold new sonic colors, flavors and adventures, including “And the Gods Made Love,” a “sound painting” featuring vari-speeded drums, distorted vocals and backwards cymbals; the lilting Curtis Mayfield-influenced lullaby “Have You Ever Been (to Electric Ladyland)”; the angry protest of “House Burning Down”; “Voodoo Chile,” a 15-minute live blues jam with Steve Winwood and the Jefferson Airplane’s Jack Casady; the slinky soul-jazz groove of “Rainy Day, Dream Away”; and the epic psychedelic apocalypse of “1983 (A Merman I Should Turn to Be).” The album also contained two tracks that would forever loom large in the Hendrix legend — the megalithically heavy “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and his radical reworking of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower.”

But while many Hendrix fans today regard Electric Ladyland as his true masterpiece, its birth was a profoundly difficult one. Recording sessions for the album, mostly split between London’s Olympic Studios and New York’s Record Plant, were regularly interrupted by touring commitments. Hendrix found himself frequently frustrated by trying to make the music on tape match the sounds in his head, while his drive for perfectionism and his endless fascination with sonic experimentation wound up alienating some of his most trusted colleagues. And even in its completed state, Electric Ladyland didn’t end up sounding (or looking) quite like Hendrix had envisioned.

On November 9th, Sony Legacy will offer additional insight into the multi-layered and -hued work with the release of a massive 50th-anniversary box set that includes outtakes, demos, a new 5.1 surround-sound mix by Electric Ladyland engineer Eddie Kramer and the 1987 documentary At Last … the Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland.

In honor of the album’s 50th anniversary, here are 10 things you might not know about Electric Ladyland.

1. Whitney Houston’s mom sang backing vocals on “Burning of the Midnight Lamp.”

The first song recorded for Electric Ladyland, the introspective “Burning of the Midnight Lamp,” was tracked at New York’s Mayfair Studios on July 6th and 7th, 1967, just three weeks after the Experience’s incendiary performance at the Monterey Pop Festival. Though written during the sessions for Axis: Bold as Love, it hadn’t been recorded in time to make the cut for that album.

The “Burning” sessions marked the first time that Hendrix worked with engineer Gary Kellgren; the two hit it off beautifully, and Kellgren would go on to play a major role in the making of Electric Ladyland. When Hendrix and producer Chas Chandler decided that the song needed female backing vocals, Kellgren’s wife, Marta, hired the Sweet Inspirations, an in-demand vocal quartet led by Emily “Cissy” Houston, whose young daughter, Whitney (just three years old at the time), would go on to become an immensely successful singer in her own right. Though Hendrix’s psychedelic music seemed a little unusual to Houston and her cohorts — who had already done sessions for the likes of Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Solomon Burke and Van Morrison — they were more than up for the challenge.

“They all thought it was quite strange,” Chandler recalled in At Last … the Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland. “ ‘Midnight Lamp’ sort of threw them a bit, but they liked it, and they did a great job.”

2. Hendrix played a homemade kazoo on “Crosstown Traffic.”

“The wah-wah pedal is great because it doesn’t have any notes,” Hendrix told Rolling Stone in 1968, waxing rhapsodic about the then-new invention, which was one of his favorite musical tools. But while Hendrix loved to experiment with the sonic possibilities of new guitar gear, he also wasn’t afraid to go the DIY route when the occasion called for it. On “All Along the Watchtower,” he used a cigarette lighter as a guitar slide — and to achieve the right buzzing effect on “Crosstown Traffic,” he doubled the guitar line by blowing through a kazoo constructed from a comb and cellophane.

“He was doing ‘Crosstown Traffic,’ and couldn’t seem to get the sound that he was trying to express across,” Hendrix’s friend and confidante Velvert Turner explained in At Last … the Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland. “Jimi said, ‘Do you have a comb on you, man? Give me a comb. Somebody get me some cellophane.’ If you take a comb and put cellophane across it and blow through it, it gives a kazoo sound. So the guitar solo on ‘Crosstown Traffic,’ the guitar is laced by the sound of a kazoo, and that’s Jimi with this particular comb. Which I just thought was amazingly brave for someone to do. Jimi would reach out and grab anything he possibly could get his hands on if he thought it could produce the desired sound for him.”

3. Brian Jones tried (and failed) to play piano on “All Along the Watchtower.”

Hendrix often encouraged other musicians to join in on his recording sessions, and Electric Ladyland featured several guest contributors, including Al Kooper, Buddy Miles and three members of Traffic (Dave Mason, Steve Winwood and Chris Wood). But when a certain member of the Rolling Stones showed up at Olympic Studios during the recording of “All Along the Watchtower,” his enthusiastic attempts to add a piano to the track were quickly foiled by his level of inebriation.

“None other than Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones stumbled by the session, decided to help out and play some piano,” Eddie Kramer recalled in At Last … the Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland. “I think he valiantly tried for a couple of takes, but it was abandoned, and they went back to cutting the basic track without him.” Not wanting to hurt his friend’s feelings, Hendrix moved Jones over to percussion; the rattling that punctuates the song’s intro is the sound of Jones hitting a vibra-slap.

4. Bob Dylan thought Hendrix’s version of “Watchtower” was an improvement on his original.

“I love Dylan,” Hendrix enthused to Rolling Stone in 1969. “I only met him once, about three years ago, back at the Kettle of Fish [a folk-rock-era hangout in New York] on MacDougal Street. That was before I went to England. I think both of us were pretty drunk at the time, so he probably doesn’t remember it.”

While Hendrix performed several Dylan covers before he died in 1970, including “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” and “Drifter’s Escape,” his masterful overhaul of “All Along the Watchtower” was his ultimate tribute to the singer-songwriter. Dylan himself has praised the Electric Ladyland version on several occasions, even incorporating Hendrix’s arrangement of the song into his live performances. “It overwhelmed me, really,” he told the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel in 1995, when asked about Hendrix’s take on the song. “He had such talent, he could find things inside a song and vigorously develop them. He found things that other people wouldn’t think of finding in there. He probably improved upon it by the spaces he was using. I took license with the song from his version, actually, and continue to do it to this day.”

5. The all-star jam “Voodoo Chile” was Hendrix’s attempt to re-create the atmosphere of his favorite NYC club on record.

“I like after-hour jams at a small place like a club,” Hendrix told journalist John Burks in February 1970. “Then you get another feeling. You get off in another way with all those people there. You get another feeling, and you mix it in with something else that you get. It’s not the spotlights, just the people.”

During the making of Electric Ladyland, Jimi’s favorite place in New York City for after-hour jams was the Scene, a popular nightclub located in a basement on West 46th Street, just around the corner from the Record Plant, a new recording studio built by Gary Kellgren with Hendrix in mind. The Scene was a magnet for touring musicians, and it was not unusual for Hendrix to spend a few hours jamming at the Scene with whoever was there, and then head back to the Record Plant for some late-night recording. On the night of May 2nd, 1968, after encountering Steve Winwood and Jack Casady at the Scene — both of their bands were in town for gigs at the Fillmore East — he brought them back to the studio and instructed Eddie Kramer to set up the microphones for a Scene-style jam session with Mitch Mitchell on drums.

“We had been over at the Scene all night when Jimi said, ‘Hey, man, let’s go over to the studio and do this,’” Kramer recalled in At Last … the Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland. “The idea was to make it sound as if it was a live gig.” Three takes later, the slow blues “Voodoo Chile” was committed to tape for posterity; audience sounds were subsequently overdubbed to give it more of a “club” vibe.

6. “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” was recorded off-the-cuff while the band was being filmed for a TV documentary.

The day after “Voodoo Chile” was recorded, Hendrix returned to the studio with Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell to be filmed for a possible ABC-TV documentary. Though the musicians were supposed to only pretend that they were recording, Hendrix seized the moment to teach his bandmates a new song — and three takes later, with the tapes rolling, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” was born.

“We learned that song in the studio,” Redding told author John McDermott. “They had the cameras rolling on us while we played it.” “We did that about three times because they wanted to film us in the studio, to make us [imitates a pompous voice] ‘Make it look like you’re recording boys,’ ” Hendrix told John Burks. “One of them scenes, you know, so ‘OK, let’s play this in E; now a-one and-a-two and-a-three,’ and then we went into ‘Voodoo Child.’ ” Though the studio footage was never used by ABC, and has since been sadly lost, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” remains one of the heaviest and most potent tracks ever recorded by Hendrix.

7. Hendrix’s studio perfectionism caused his manager/producer to quit during the making of the album.

While both “Voodoo Chile” and “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” were recorded in three takes apiece, such spontaneity was in short supply during the making of Electric Ladyland, much to the chagrin of Chas Chandler, Hendrix’s manager and producer. Chandler, who far preferred the “hit it and quit it” method of record making, grew increasingly frustrated with Hendrix’s perfectionist tendencies — as exemplified by the four-dozen takes he required for the funky field holler “Gypsy Eyes” — and the party atmosphere that dominated many of the Record Plant sessions.

“I would go in there [to the Record Plant] and wait for Jimi,” Chandler told author John McDermott, “and he would show up with eight or nine hangers-on. When he finally did begin recording, Jimi would be playing for the benefit of his guests, not the machines….We’d be going over a number again and again and I would say over the talkback, ‘That was it. We got it.’ He would say, ‘No, no, no,’ and would record another and another and another. Finally I just threw my hands up and left.”

Experience bassist Noel Redding was also extremely unhappy about the festivities surrounding the sessions, as well as the fact that Hendrix — in his quest to get everything exactly like he heard it in his head — had decided to play bass on many of the album’s tracks, thus leaving Redding with little to do. “I took it out on Jimi,” Redding wrote in his autobiography, Are You Experienced?, “letting him know what I thought of the scene he was building around himself. There were tons of people in the studio, you couldn’t even move. It was a party, not a session. He just said, ‘Relax, man …’ I’d been relaxing for months, so I relaxed my way right out of the place, not caring if I ever saw him again.” Redding would eventually return to the sessions (even singing lead on “Little Miss Strange,” a track he’d penned that Hendrix dug enough to include on the album), but Chandler was gone for good.

8. Hendrix’s U.K. label neglected to inform him that they were putting naked women on the album’s cover.

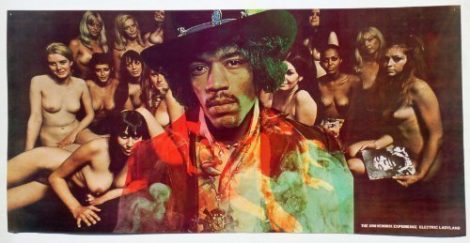

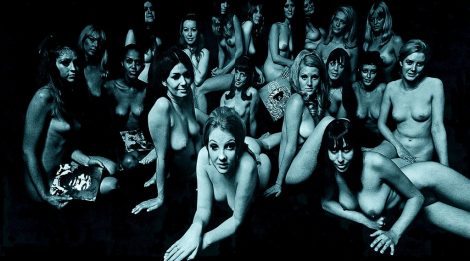

In addition to being a musical perfectionist, Hendrix had very specific visual ideas for Electric Ladyland. Photographer Linda Eastman, who would marry Paul McCartney the following year, had taken a photo of the Jimi Hendrix Experience hanging out with some children on José de Creeft’s Alice in Wonderland sculpture in New York’s Central Park, and Hendrix thought it would be perfect for the cover of the album. “Please use color picture with us and the kids on the statue for front or back cover — OUTSIDE COVER,” he instructed Reprise Records, his U.S. label. For whatever reason, Reprise opted instead to use a solarized Karl Ferris photo from Hendrix’s 1967 performance at London’s Saville Theatre — while Track Records, Hendrix’s U.K. label, took a more provocative and controversial tack by using a David Montgomery photo of 19 nude women.

According to a December 7th, 1968, news article in Rolling Stone, the Track release of the album “met resistance and censorship in many record shops and outlying provinces in the British Isles,” while London wholesalers were only selling the record with a nudity-obscuring brown wrapper. Hendrix, for his part, claimed he hadn’t been informed about Track’s plans for the album cover.

“I didn’t know a thing about the English sleeve,” he told Melody Maker in November 1968. “Still, you know me, I dug it anyway. Except I think it’s sad the way the photographer made the girls look ugly. Some of them are nice looking chicks, but the photographer distorted the photograph with a fish-eye lens or something. That’s mean. It made the girls look bad. But it’s not my fault.”

9. Hendrix was unhappy with the way the finished album sounded.

While Hendrix spent long hours in the studio recording Electric Ladyland — running up a $60,000 bill at the Record Plant and $10,000 at Olympic (or more than half a million dollars in 2018 terms) with his round-the-clock work — he unfortunately had no such luxury when it came to the final mix. Pressured by Reprise for a finished product, he was forced to mix the record while out on tour with the Experience.

“It’s very hard to concentrate on both,” he lamented to Hullabaloo magazine, shortly after the album’s release. “So some of the mix came out muddy — not exactly muddy but with too much bass. We mixed it and produced it and all that mess, but when it came time for them to press it, quite naturally they screwed it up, because they didn’t know what we wanted. There’s 3D sound being used on there that you can’t even appreciate because they didn’t know how to cut it properly. They thought it was out of phase.”

10. Rolling Stone gave the album a mixed review upon its release.

Electric Ladyland sounded like nothing else when it was released in October 1968, so it’s not entirely surprising that many contemporary reviewers were unable to fully get their heads and ears around its 75 minutes of sheer awesomeness. Tony Glover — writing about the album for Rolling Stone’s November 9th, 1968, issue — gave Electric Ladyland a decidedly mixed review, one which praised the album’s more straight-ahead blues excursions (as well as “All Along the Watchtower”) but he seemed unsure about its heavier moments, and specifically bemoaned the way Hendrix’s wailing guitar upset “the beautiful undersea mood” of “1983.” “My first reaction was, why did he have to do that?” Glover wrote. “Then I thought that he created a beautiful thing, but lost faith in it, and so destroyed it before anybody else could — in several ways, a bummer.”

Thirty-five years later, however, the album achieved its rightful due in Rolling Stone, landing at number 55 on the magazine’s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

Source:

You must be logged in to post a comment Login