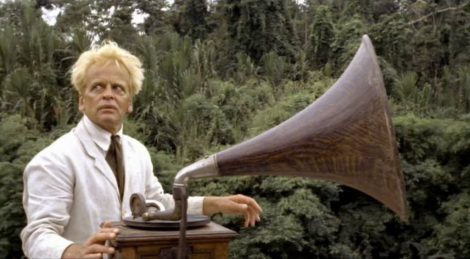

In Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, the jungle, oppressive and thick, provides the perfect backdrop to the ambitions and lunacy of men. Obsession weighs heavy on Fitzcarraldo (Klaus Kinski), a man consumed with a plan to build an opera house in the heart of the Amazon. In order to fund the project, he intends to make his fortune in rubber. He is able to cheaply purchase a plot of land, which cannot be easily accessed due to deadly rapids. To overcome this, he plans to take a steamship down a neighboring river and, if you can possibly imagine, over a mountain standing between the two waterways. Throughout his journey, Fitzcarraldo’s mania is unwavering and intense. Before departing, he appears to be the face of madness as he, bug-eyed with blonde hair standing on end, stands atop a cathedral, ringing the church bell and shouting for his opera house. Fixation, however, permeates the film beyond its main character, and is deeply rooted within the core of the film.

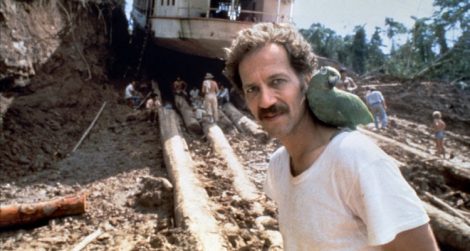

Fitzcarraldo’s obsessions closely mirror those of the film’s director. Just like his protagonist, Herzog is fueled by an intense, creative passion that pushes him to accomplish the unimaginable. The filming of Fitzcarraldo was most definitely a trial. It took over three years of hardship deep in the Amazon to bring the film to completion, and the struggles gone through by Herzog and his crew are evident within the film. When Fitzcarraldo’s steamboat inches its way up the mountain, Herzog rests on the image for some time. It isn’t sweeping or impressively cinematic, but what need would this moment have for such superfluity? The simple idea that this is really happening, this feat against nature is occurring before you, is more than enough to keep an audience completely mesmerised. But, even in this trance, one wonders, does all the hardship and toil gone through in the name of a dream give it some higher value? Does the story behind the film elevate it as a work of art? Should it? Witnessing the boat’s journey tempts one to agree. If shot on a soundstage, the scene, devoid of its distinctive, infeasible authenticity, would hardly carry the significance that it does and, in some way, the film would be made pointless. However, in Burden of Dreams (Les Blank), a documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo, an exhausted Herzog, still slogging through filming, states even if his project is successfully completed, “nobody on this earth will convince me to be happy about that, not until the end of my days.”

At the film’s end, a celebrating Fitzcarraldo drunkenly falls asleep after the steamboat finally descends over the mountain. Before he can rejoice, the native people who have assisted him, spiritually motivated, cut the boat loose. It drifts into violent rapids and, now battered, Fitzcarraldo has no choice but to sell it. His dream is dead. But before completely resigning himself to failure, Fitzcarraldo uses the last of his funds to rent out a small-time, local opera and, with a huge cigar at his lips, proudly listens as they all float home down the river. The moment isn’t quite victorious, and again, one questions if this meager end justifies the means. Though perhaps Fitzcarraldo did not realize his dream, Herzog certainly did. – Hadley Pack

The best thing about the film Fitzcarraldo is its production story. It is heartbreaking to watch Burden of Dreams, a wonderful documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo, knowing how unenjoyable the movie itself turned out. The plot surrounds a European man named Brian Fitzgerald, otherwise known as Fitzcarraldo (Klaus Kinski), who wishes to bring opera to the small Peruvian town he lives in by building an opera house in the jungle. To do this, he must harvest rubber from the surrounding wildlife and get help from the local native peoples to drag his boat over a hill from one river to the next.

Before delving into the bad, there were a few enjoyable pieces of this film. The first is the fantastic cinematography. Fitzcarraldo is chock-full of slow pans of the forest that risk boring the viewer, yet sustain one’s interest due to the beautiful jungle, interesting composition, or one of the many exotic animals caught on film. Shots of note are the opening pan of the forest from the treetops, a small light illuminating Fitzcarraldo as the red-painted faces of the natives create a wall behind him, and the large boat being dragged ever so slowly over the hill, puffs of smoke from its funnel clouding the sky.

The soundtrack was another strong point of the film. Fitzcarraldo is obsessed with the opera singer Enrico Caruso, and Caruso’s magnificent voice is played quite often throughout. The European opera contrasts nicely with the surrounding wildness of the jungle, as well as the native people’s music that is played later on, foreshadowing their clash of culture. It was a nice detail that almost all of the music played was diegetic; actually in-scene and heard by the characters. It’s a stylistic choice that is deserved and makes sense considering music’s importance in this movie’s plot.

Here are just a few bits of the long, crazy tale of the production of Fitzcarraldo, a story much more interesting than Fitzcarraldo itself. The director, Werner Herzog, mirrors Fitzcarraldo uncannily in his near-insane levels of commitment to his art, and his willingness to push himself and others forward into obvious danger. The entire movie is filmed on-location in the Amazon, 500 miles from the nearest city. A crew member cut his own foot off with a chainsaw after being bitten by a snake. The original actor playing the main character, Jason Robards, had to quit after coming down with dysentery. They actually managed to lug the huge boat over the hill using a rope and pulley system, even when there was an estimated 70% chance that it would fail and possibly crush 20-30 people.

Fitzcarraldo is a long, boring film that dawdles around for a good half an hour before finally getting to the plot. It feels as if there are plenty of scenes that could be cut from the movie entirely with little to no change to the experience, especially in the beginning. There is little to care about unless one is infatuated with the opera, as the characters aren’t written well enough to be likeable or interesting. All the characters seem two-dimensional except the main character, Fitzcarraldo, whose motivations are stupid and personality is easily dislikable. It’s difficult to care about a rich, white man attempting to bless the native population of Peru with his culture’s music, especially when most of those people are probably struggling to survive in their harsh living conditions. How does he think this is a worthwhile ambition? How does he think that any of these people can afford to go to an opera? Would they even want to? It’s of little matter to Fitzcarraldo, who is so obviously infatuated with his own dream that he compares himself to a god for the native people: “God does not come with cannons, but with the voice of Caruso.” This would be fine if Fitzcarraldo was supposed to be a dislikable character to prove a point or unveil some truth, but there seems to be little evidence that the audience isn’t supposed to like him, especially when considering his good fortune, the light tone of the movie, and the ending.

The acting doesn’t help the likeability of the characters, either. In both the German and English dubs (though it’s much worse in the English version) everything is said with a dramatic intensity that belongs in a bad T.V. soap-opera. The worst offenders were Don Aquilino (Jose Lewgoy), a rubber baron, and Molly (Claudia Cardinale), Fitzcarraldo’s love interest. Aquilino is supposed to be an unlikeable, racist old man who Fitzcarraldo doesn’t care for but needs to get into the rubber business. It seems that through seeing how bad Aquilino is the viewer is supposed to identify with and forgive Fitzcarraldo for his faults. However, Aquilino’s character is so overdone he’s one step away from a mustache-twirling villainous mastermind from a superhero comic book, complete with maniacal laugh. Molly’s character doesn’t suffer from her acting, persay, but the amount of extra huffs, puffs, laughs, gasps, and general dramatized, non-verbal noise the actress makes in between sentences is hilarious at points.

The portrayal of the native Amazonian tribe in relation to Fitzcarraldo and his ship is offensive and not realistic. They seem to be a mystical, benevolent (to the protagonist, anyways) force of nature rather than an actual people with minds of their own. Yes, it is true that in the end they do send the ship back down the river from whence they came. But this seems like a cheap excuse for a whole bunch of behavior that just doesn’t make sense. If these are people with a reputation for killing anyone who enters their territory, why don’t they for this specific ship? Why do they decide to work for Fitzcarraldo, when they can’t understand his language and, most likely, his intentions? It all just seems to be because he’s white. It is even said in the movie: “The natives expect salvation from the white vessel.” There are scenes in which the native people touch him curiously, gazing at his paleness in awe.

The way Fitzcarraldo abuses this power is sickening. He uses the native people for hard labor and puts them in great danger, not expecting to pay anything substantial in return. When an explosion goes off and terrifies a group of natives, Fitzcarraldo hushes the silly “bare-asses” and motions for them to go back to work. And they do, for no reason at all, because they shouldn’t be able to understand him. One even is crushed under the boat as it slides back down the hill and dies, and the natives stop working for a while, but only a few days. The shots of Fitzcarraldo in a glowing white suit surrounded by a sea of working native people is reminiscent of a plantation owner. When down about how some things are going poorly, he says: “We have the strength of hundreds of Indians.” It leaves a sour taste in one’s mouth. Again, this would all be fine if Fitzcarraldo were meant to be a hated character. However, the ending of the movie suggests that he is not.

To finish it all off, Fitzcarraldo has an extremely anticlimactic and unsatisfying ending. After dragging the boat over the hill, the natives send it back down the river and into the deadly rapids they were attempting to avoid in the first place. These are waters that were hyped up the entire film to be deadly and dangerous, and yet nothing bad happens because they went through them. The ship isn’t damaged, no one dies, no one is injured, nothing is lost, rendering them going over the hill to avoid the rapids in the first place useless after all. While Fitzcarraldo does lose his ridiculous dream of having an opera house in the jungle, he doesn’t seem to broken up about it. At the end, he scrapes up enough money to have a single opera show on his boat before he sells it and makes his money back. Fitzcarraldo sails around his Peruvian hometown, smiling and smoking a fat cigar as music swells and people rejoice. This is a problem. Throughout the entire film, this egotistical, crazy white knight abuses his power and to get something out of the film the viewer would usually want him to either learn a lesson, change, or for some point to be made about race or cultural differences. Instead, the only thing Fitzcarraldo seems to have learned is that building an opera house in the Amazonian jungle is a stupid idea, and it’s not even certain if he knows that. The story goes from nothing to nothing.

All in all, the only good reason to watch Fitzcarraldo is to prepare for the fantastic documentary on its making. Burden of Dreams has a more interesting story, more likeable people, a more satisfying arc, and a better message. It depicts the native tribes as what they are– humans. And while Werner Herzog does share Brian’s insane passion for his art and his tendency to endanger others, from what can be gathered from the documentary he pays his workers fairly, and warns them of the dangers. He is seen talking to the native people and showing them respect, and his goal was an achievable one. It’s a shame the film turned out the way it did. – Emerald Seale

Les Blank’s documentary Burden of Dreams was a brilliantly executed interpretation of the production behind Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo. While Herzog’s zany personality and far-fetched dreams for his film are supposedly the focus of the documentary, the more interesting story lies in the lives of the actors. Hundreds of native Peruvians participated in the production of the film, which required not only acting, but hard, physical labor. Herzog’s dream was to create a film in which a man pulls a 30-ton steamship over a mountain, and his reputation of going to the extreme followed him to this production as well. It was because of Herzog’s outrageous attempt that Blank was invited to film the production. However, Blank’s final product is closer to an ethnographic study of the natives in the film. I was pleasantly surprised with the respectful nature of the documentary considering the blatant racism shown in Herzog’s film. After Brian Fitzgerald (Klaus Kinski), the lead role in Fitzcarraldo, treated the natives as a singular magical force dedicated only to working for his dream, I was expecting Werner Herzog to have a similar manner about him.

However, I found Herzog to be much more considerate and open-minded when it came to the treatment of the native people working on his film. He provided separate living spaces during the filming to respect the cultural differences and made sure they had what they needed to thrive in the environment. He even took up a Catholic priest’s suggestion to make prostitutes a part of the crew to keep the men from going crazy in the jungle for so long. While this decision might have been questionable, it does show an interest in the well-being of the members of his crew with whom he is less familiar. To me it is because of his considerate acts just as much as his close-to-comical view of the world that makes him so much more likeable than his character, despite all their similarities. It is an unfortunate reality that the creation of Herzog’s dream led to the injury and death of so many people due to the harsh environment of the jungle in which they filmed. Through the creation of the film, there were two plane crashes, a drowning, a few deaths from disease, and a self-amputation due to a venomous snakebite. Because of this, Herzog said, “Even if I get that boat over the mountain, nobody on this earth will convince me to be happy about that…not until the end of my days.” And that deserves more respect than I could ever grant to Brian Fitzgerald.

The documentary itself was beautifully shot, and I specifically enjoyed the mimicking of Fitzcarraldo’s soundtrack. Burden of Dreams used the same operatic music that was played throughout the original film, but this time it took turns with music played and sung by the native people working on the film. While the documentary did give me a greater respect for Fitzcarraldo and for Herzog, it did not help me to enjoy Herzog’s film, which I still find to be boring and unpleasant. Burden of Dreams went above and beyond expectations to present the viewer with the most interesting subjects, images, and sounds that made up Fitzcarraldo. – Havana Soler

Source: The Pigeon Press

http://thepigeonpress.org/three-perspectives-fitzcarraldo/

You must be logged in to post a comment Login