Playing with the boundaries between the visual and the musical is an old game. The Pythagoreans were probably the first westerners at it when they declared: “The eyes are made for astronomy, the ears for harmony, and these are sister sciences.” This relatively simple proposition was taken up by medieval and later sages, who developed it into a vast intellectual undergrowth of arcane and convoluted theories of how music and the mathematical proportions of creation were one and the same.

The Romantics had their own, similar, thoughts: Goethe declared that architecture was “frozen music”, and the mid-Victorian über-aesthete Walter Pater breathlessly announced that “all art aspires towards the condition of music”. By the late 19th and early 20th century, however, blurring the edges between music and the other arts had become a widespread obsession. The idea fitted with the spirit of an age when artists and commentators from Russia to America were embracing pseudo-religions, dabbling in pseudo-sciences of dreams and symbols, and gabbling with excitement about the prospects for a new synthetic experience of art where the material distinctions between word, image and sound would melt away into a kind of spiritual – though it often seems more sexual – ecstasy that would shake the body and the world. Poems and paintings became music, and music became paintings and poems.

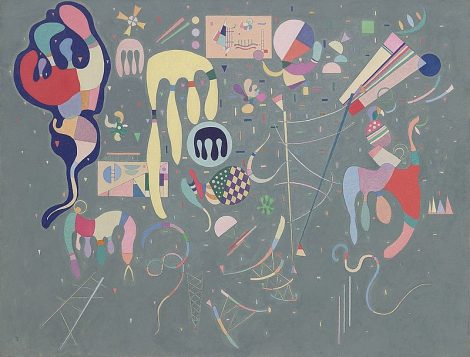

This was when the gaudy flowers of Wassily Kandinsky’s paintings burst from their buds. Music – and the idea of music – appears everywhere in Kandinsky’s work. Take his generic titles: Compositions, Improvisations, and Impressions. His mighty 10 compositions were created over more than three decades from Composition l in 1907 to Composition X in 1939. The first three were destroyed in the second world war but enough survives in sketches and photographs to give an impression of what they were about and how they fitted into a sequence of paintings that aspires to be, in musical terms, a cycle of “symphonies”. The Improvisations are, on the whole, less monumental, more dramatic. One writer compared them to “concertos”. Kandinsky himself called them “suddenly created expressions of processes with an inner character”. And as for the Impressions, although this may seem less of an obviously musical title, we know that several of them were specifically written in response to the experience of hearing particular pieces of music.

There are also one-off titles by Kandinsky with musical intentions. In Moscow in 1903 he published 122 primitive-looking woodcuts that he called Poems Without Words, clearly having in mind the old musical genre of “songs without words”. In 1913 he created a book of linked poems and woodcuts called Klänge – “Sounds”. During this same prewar period he wrote several play scripts – more like opera librettos or film scripts – to which he gave titles like The Yellow Sound, The Green Sound and Black and White. Though hardly stageable, these pieces were intriguing experiments in the synthesising of drama, words, colour and music into a single seamless whole.

Also at this time Kandinsky wrote his famous theoretical work On the Spiritual in Art. This classic text of early modernism brims with the “spiritual” enthusiasms of the age. But it is also remarkably precise about what Kandinsky considers the practical stuff of his art, and especially about colour, ascribing particular emotional (“spiritual”) qualities to each shade, grouping them into families of like and unlike, and proposing complex ways in which contrasted colours could be balanced with one another. As is dazzlingly evident from the art he produced at this period, Kandinsky’s fundamental idea of a unifying colour-theory, however outré or whimsical it might appear, played a big part in enabling his astonishing imaginative leap into abstraction.

To support his colour theories, Kandinsky appealed in his manifesto to the evidence of synaesthesia, the scientific name for the condition in which the senses are confused with one another (as when someone hears the ring of a doorbell as tasting of chicken or whatever). He wrote enthusiastically of how “a certain Dresden doctor tells how one of his patients, whom he describes as ‘spiritually, unusually highly developed’, invariably found that a certain sauce had a ‘blue’ taste”. This touching medical support for the idea that a spiritually superior person will naturally perceive the significance of the kinds of colour connections that he is talking about leads Kandinsky on to a grandiloquent cascade of musical metaphor:

“Our hearing of colours is so precise … Colour is a means of exerting a direct influence upon the soul. Colour is the keyboard. The eye is the hammer. The soul is the piano with its many strings. The artist is the hand that purposely sets the soul vibrating by means of this or that key. Thus it is clear that the harmony of colours can only be based upon the principle of purposefully touching the human soul.”

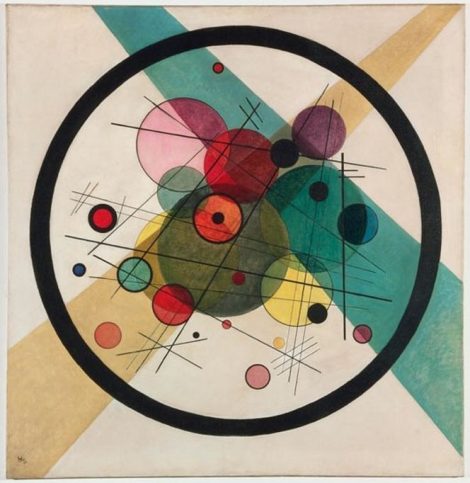

The heart of Kandinsky’s connection to music, of course, is found not in his titles or theoretical self-justifications but in his works of art. And here it is clear that however arbitrary his scaffolding of theory, he had genuinely arrived at a way of playing on the canvas with the tensions and relationships between pure colours. In an eloquent essay in the catalogue to the Tate Modern’s forthcoming exhibition, Kandinsky: The Path to Abstraction 1908-1922, the German artist Bruno Haas speaks of the clarity of Kandinsky’s painterly “syntax” and describes how Kandinsky’s families of colours resonate with one another to produce visual “chords”. As if aware that we might not believe him, Haas suggests ways in which we can prove to ourselves the existence of these “chords” by taking a colour print of one of Kandinsky’s pictures and holding down our hands over this bit or that to see how the colours (and shapes) change in relation to one another. He quotes a vivid line from Kandinsky describing the experience of painting in this way and once again using a musical metaphor:

“I had little thought for houses and trees, drawing coloured lines and blobs on the canvas with my palette knife, and making them sing just as powerfully as I knew how.”

Although Kandinsky’s hyper-Romantic language of musical and sensual connections is vivid and often original, it was also of its time. At this period many artists and adventurers, often of quite different cultures, talked in generally similar terms. WB Yeats’s journals of his early London years touch on some of the same themes, French art and music of the Debussy era is full of associations and theories of this kind, and the Viennese were given an especially fruity prompt in this direction by Freud. It was Vienna that produced for Kandinsky perhaps his most remarkable artistic friendship, with the composer Arnold Schoenberg. In 1911, Kandinsky heard a concert of Schoenberg’s music and realised he had found a comrade-in-arms. The two began a long and often stormy friendship involving fierce criticism of one another’s works, and the intense sharing of ideas and influences. Schoenberg, who was also a painter and writer, was as deeply involved in the idea of breaking down the barriers between the different arts as Kandinsky. Nowhere is this more vividly seen than in their theatrical experiments of these years. In 1909, Kandinsky wrote the mysterious text of his proposed music-drama The Yellow Sound (the composer was supposed to be Thomas de Hartmann, who later worked with the “mystic” Gurdjieff). The fifth scene begins:

“The stage is gradually saturated with a cold, red light, which slowly grows stronger and equally slowly turns yellow. The giants become visible as do the rocks.”

The following year, Schoenberg wrote the libretto for his opera The Lucky Hand. The second scene begins: “In the background a soft blue, sky-like backdrop. Below, left, close to the bright brown earth, a circular cut-out five feet in diameter through which glaring, yellow sunlight spreads over the stage.” Both Kandinsky and Schoenberg were seeking to create music dramas in which colour would be perceived on the same level as sound and action. And this before the invention of modern lighting.

There was something else about Kandinsky, however, that separated him from many of his German and French contemporaries. He was a Russian. Born in 1866 in Moscow and brought up there and in the southern city of Odessa on the Black Sea, he was steeped in the habits and passions that characterised so much Russian art from Dostoevsky to modernism.

Take synaesthesia, for example. Dostoevsky touched on this subject when making notes about his experience of migraines. By the late-19th century it had become downright fashionable among Russian composers to claim to suffer, or take pleasure and inspiration, from this condition. Always it was the same brand of synaesthesia, the confusion of sound and colour, even though, as Richard Cytowic – the modern authority on synaesthesia – has pointed out, this is in fact an extremely rare variety. So Rimsky-Korsakov, a composer a generation older than Kandinsky, was convinced that he heard musical keys as colours, while Scriabin, a composer of Kandinsky’s own generation, not only declared that he heard keys and chords as colours, but composed his sumptuous orchestral work Prometheus: Poem of Fire in 1909-10 to include a “colour keyboard” illuminating the concert hall with a flood of colours and transporting the meaning of the music into another dimension. To help us, Scriabin wrote out in schematic form his personal vocabulary of music-colour-emotion. Though almost in the manner of Kandinsky, it is of comical clunkiness: C major = The Human Will = Deep Red, G major = Creative Play = Orange, and so on. Unsurprisingly, given such preoccupations, Scriabin, along with Schoenberg, was one of several musical contributors to The Blue Rider, the pioneering magazine that Kandinsky and a group of like-minded artists issued in 1912.

Similar concerns are also found in the work of many of the modernist and experimental writers who flourished in Russia in the very early 20th century. To take one example, between 1899 and 1908, the brilliant novelist Andrey Bely wrote four substantial prose-poems that he called “Symphonies”. In them, he unfolded dream-like sequences of symbols, echoes of myth and fragments of real life, held together by nothing much more than the sound and rhythm of the language and vague suggestions of formal signposts borrowed from classical music. In other words, in his symphonies Bely was attempting to endow language with the same supposedly abstract qualities of music that Kandinsky was trying to introduce into painting in his Compositions, Improvisations and Impressions. Interestingly, along with several other Russian colleagues, Kandinsky and Bely fell deeply under the influence of Rudolph Steiner at this time, a fact that significantly affected their creative practice.

Beyond music, writing and painting, the dominant art in Russia at the dawn of the 20th century was theatre. This, after all, was the age not only of Stanislavsky, but of his great pupil, the director Vsevolod Meyerhold. Meyerhold repeatedly spoke of transforming theatre into music, and caused a tremendous stir in 1909 with his epic production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, in which the colours and shapes of the sets and the movements of the singers were carefully choreographed in time to the music so that they became, as it were, part of Wagner’s score.

This was also the age of Diaghilev and his vastly successful Russian Ballet. The whole point of Diaghilev’s epic spectaculars such as The Firebird and The Rite of Spring was the way they brought together Russia’s greatest painters, composers, dancers and choreographers to create an overwhelmingly colourful, dramatic and musical experience, which was then self-consciously sold to western audiences as authentically “Russian”.

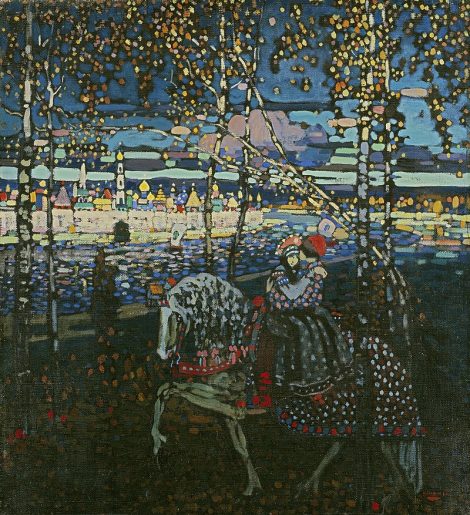

Like so many Russian emigrés, Kandinsky seems never to have doubted his cultural roots and never ceased to speculate about their importance for him. Though he spent much of his life abroad in Germany and latterly in France, he spoke and wrote constantly about Russia, and especially about his native city of Moscow and how its distinctive beauties had nurtured his peculiar way of seeing the world. Images of Russia, usually of an old Russia, surface constantly in his earlier work – troikas, brightly coloured onion domes and the rest – and even in the great paintings of his abstract period we can detect the fertilising influence of Russian icons with their own strangely abstract language of piercing colours and symbolic shapes.

When he visited Moscow in 1910 he wrote to his lover back in Germany: “I am totally in love with Moscow. It is beautiful … indescribable.” When he encountered there his fellow Russian artists and avant-gardists he was “practically delirious”. And once back in the west he felt, he said, a “never-waning longing for Moscow” and for “the soil from which I derive my strength”.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login