The author and the illusionist might seem an odd couple, but a shared interest in the afterlife made for an unlikely bond and a bitter rift.

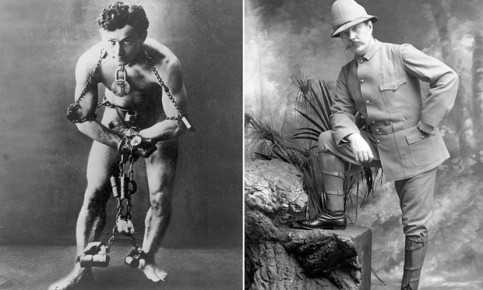

In 1920, two of the biggest celebrities of the age met for the first time. One was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the famed creator of the great detective Sherlock Holmes, and the other was Harry Houdini, the illusionist and escapologist who became one of the world’s highest-paid entertainers for his ability to escape from a steel and glass coffin filled with water in which he had been suspended upside down, or to make elephants disappear.

Some believed that Houdini was not an illusionist but had real magical powers. The actor Sarah Bernhardt apparently asked him to conjure her a new leg to replace the one she had amputated following a stage accident.

Conan Doyle and Houdini were an improbable pair. One was very much the bluff Scottish Victorian gentleman, educated at a minor Catholic private school; the other a largely self-educated Hungarian immigrant to the US who had spent most of his life in rackety vaudeville. The two men were brought together by a shared interest in spiritualism, but it was also spiritualism that destroyed this unlikely friendship.

The theatre is a place where ghosts rise. It has been described by Alice Rayner inGhosts: Death’s Double and the Phenomena of Theatre as “a specific site where appearance and disappearance reproduce the relations between the living and the dead”. Since it often also involves the audience suspending disbelief, it is a good place to explore the tale of the two men, one who believed the most important thing was to “prove immortality”, and one who feared it was impossible.

Their story is told in Impossible, a play that premieres at the Pleasance on the Edinburgh fringe with Phill Jupitus as Conan Doyle and Alan Cox as Houdini. The show plays upon the duality of theatre and the way it uses sleight of hand and sleight of mind to make us see what does not exist. Cox has even been learning some magic tricks.

Director Hannah Eidinow is fascinated that Conan Doyle, who believed he saw the faces of the dead, including his own nephew, in a photograph (later proved to be a fake) taken at the Cenotaph, once set up in practice as an eye doctor.

“There is something interesting about the way he was always so convinced by the evidence of his own eyes. Theatre is all about directing the eye,” Eidinow says, “and where people look. It’s about controlling what people see and don’t see.” Many 19th- and early 20th-century mediums used theatrical techniques. What, after all, is the spirit cabinet used by famed practitioners such as the Davenport Brothers, but a form of puppet theatre that appears to animate the dead?

Following the death of his son, Kingsley, during the first world war, Conan Doyle became a devout believer in life after death and an untiring missionary for the spiritualist cause, donating the equivalent of millions of pounds in today’s money in trying to prove that the dead were all around us and eager for a chat.

Houdini, the showman, longed to believe that he might be able to communicate beyond the grave with his beloved mother, but knew far too much about the trickery and faking of the stage to be easily convinced. Early in his career, before he found fame as an escape artist, Houdini and his wife, Bess, were not above drawing on their own theatrical skills to give public seances on the vaudeville circuit in order to ensure there was bread on the table.

It was Houdini’s public campaign to expose fraudulent mediums who he described as “human leeches” – particularly Margery Crandon, a Boston medium who performed scantily clad and on occasion apparently emitted ectoplasm from her vagina – that led to a rift between the two men that had not healed by the time that Houdini died from a ruptured appendix in 1926.

Conan Doyle, a medical doctor and the creator of that great rationalist, Sherlock Holmes, might seem like an unlikely person to fall for the claims of mediums. But from the mid-19th century onwards, spiritualism had a widespread following both in the UK and across the Atlantic, its rise coinciding with the industrial revolution and a period of great technological and scientific advances.

“Maybe,” suggests Cox, “the faster that new technologies bring change and the more we think we know about the world or how it works is being explained to us, the more we look for something beyond, something that can’t be explained. It could be the inner world of the imagination and theatre, which is a kind of magic, or something like spiritualism.”

The huge loss of life in the first world war only gave spiritualism more converts. Public seances in the Albert Hall and other huge venues were common, and the appeal of the movement cut across the classes. Rudyard Kipling’s sister was a society medium, and while Conan Doyle might have been teased in some quarters for his belief in the authenticity of the fairy photographs taken by two young cousins in 1917 at Cottingley in Yorkshire, his claims that there was an afterlife and a direct conduit between our world and the next was treated with respect by many, including the media.

Conan Doyle’s own wife, Jean, became a self-proclaimed medium and purveyor of automatic writing. At their Sussex home, they had their own personal spirit guide called Phineas who regularly predicted global catastrophe. Phineas also dictated when the Doyles should move house or travel. In his entertaining book Houdini and Conan Doyle: Friends of Genius, Deadly Rivals, Christopher Sandford recounts an occasion when Jean got the local station master to reschedule a train that her husband was due to take on the advice of Phineas. The counsel of Phineas, it appears, quite often chimed with the desires and interests of Jean herself.

In fact, it was after Jean’s attempt to contact Houdini’s mother during a seance in a hotel room in Atlantic City in 1922 that serious cracks in the men’s relationship began to appear. Although following the private seance, in which Houdini’s mother apparently made contact via automatic writing, the Doyles thought he Houdini appeared deeply moved, he subsequently publicly announced that he did not believe that the 15 pages of grammatical English were a genuine message from beyond the grave. Not least because his mother’s English had been terrible.

The relationship barely survived that incident, and when Houdini increasingly denounced mediums who Conan Doyle was convinced were utterly genuine, their relationship broke down.

“There may have been an element that Houdini knew that in denouncing spiritualism it kept him in the headlines, but I think that he was being cruel to be kind when he told people, Conan Doyle included, that they were being deceived, because he thought grief was making them susceptible to charlatans,” says Cox. “He wanted spiritualism to be true, but he was convinced by his investigations that it wasn’t, and he couldn’t stand by and say nothing.”

After Houdini’s death, his widow, Bess, held a yearly seance, hoping that her husband might make contact and give her message using a prearranged code. He was always a no-show. In 1936 she gave up, supposedly declaring that “10 years is long enough to wait for any man”.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login