The purpose of this essay is to offer a Deleuzian time-image analysis of Tarkovsky’s montage theory of “time-pressure,” foregrounded against the historical backdrop of Eisenstein’s montage of attractions. Several films from Tarkovsky’s later work will be examined for montage elements that support or contravene these theories.

The history of the post-Revolution USSR can be broken into three major periods: 1) Stalinist period (1927-1953) 2) post-Stalinist period (1953-1986) and 3) Gorbachev (and post) period (1986-). During the Stalin period the Soviet film industry was under the control of the communist regime.1

The Russian new wave began during the Post-Stalinist period, at about the same time as it did in the rest of Europe. It is characterized by films about national history and WWII, social dramas, and poetic films. The Russian new wave filmmakers are many, among them, Andrei Tarkovsky, Sergei Paradjanov, Alexei German, Tengiz Abuladze, Otar Iosseliani, and Nikita Mikhalkov. To speak of Soviet-Russian cinema is to discuss the achievements of the old and new school of film making, and one can easily begin by comparing the works and theories of Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky.

Soviet montage developed after the 1917 Russian revolution. Sergei Eisenstein is considered, if not the father of Soviet montage, its most articulate spokesperson. Soviet montage views movement and space as the distinctive characteristics of cinema as opposed to theater. Montage defines the way in which images are cut and assembled together. The director composes separated filmed fragments into a whole and juxtaposes these fragments into an integral structure to achieve a rhythmical effect. Eisenstein considered montage as the basis of art cinema (film art). The “montage of attraction” puts objects, ideas, and symbols in collision to produce an intellectual and critical response from the viewer.2

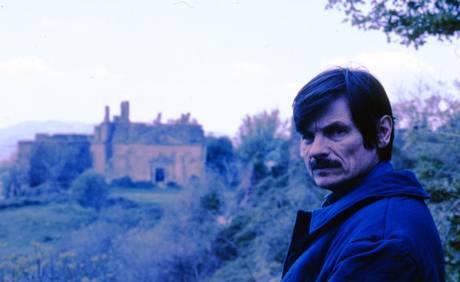

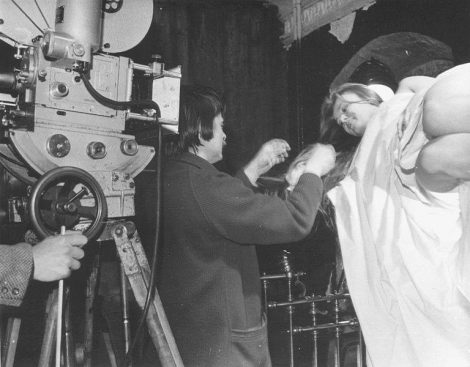

Andrei Tarkovsky is the most celebrated filmmaker of the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s (until his death in Paris on Dec. 29, 1986). He is the patriarch of the contemporary Soviet “poetic film.” Tarkovsky strongly opposed montage and believed that the basis of art cinema (film art) is the internal rhythm of the shot. Tarkovsky’s idea of “Sculpting in Time” proposes cinema as the representation of distinctive currents or waves of time, conveyed in the shot by its internal rhythm.

Tarkovsky believed the film image not to be a composite of different shots arranged in a structure within a specific sequence progressing in time. He reasoned that if the film image is not a composite then the dominant factor of the film must be its rhythm. Rhythm is at the core of the “poetic film.” But Tarkovsky’s idea of rhythm is not that of Eisenstein, instead he envisioned cinematic rhythm as some kind of movement within the frame, and not as a sequence of shots in time. Hence, the main characteristic of poetic film is the process of Sculpting in Time as opposed to Eisenstein montage of attractions. While Eisenstein’s process of editing is guided by intellectual and conceptual juxtaposition of images, Tarkovsky’s time sculpting involves editing techniques which allow spontaneous unification of the shot as a self-organizing structure. Instead of the interplay of concepts (Eisensteinian montage), Tarkovsky creates the film image as an expression of the matter world, or simply the world. For Eisenstein, the concept dictated the cut; but for Tarkovsky, it is time that rules, dictating the editing techniques. Therefore, time within the frame expresses something significant and truthful that goes beyond the events on the screen and those in the frame; and so, the direct perception of time is like a pointer to infinity (this approach is quite different to the montage of attraction between shots where elements in the shot juxtapose concepts, making the viewer produce some intellectual link). While the montage of attraction produces a burst of meaning, arousing the viewer with the purpose to suggest specific ideas and concepts, Tarkovskian time rhythms illustrate a way of seeing life in its essence, life’s movements. Moreover, this poetic expression of the material world may go beyond the artist’s intention and be received differently by each viewer. In the Tarkovskian School of film poetics, the filmmaker expresses his philosophy of life as opposed to creating a new perception of a social reality.

More typical than Paradjanov’s treatment as a film director was the plight of Andrei Tarkovsky [1932 – 1986], the second major figure from the postwar Soviet cinema during the sixties.3 Tarkovsky was probably influenced in his decision to study at the VGIK (Moscow film school) under Mikhail Romm by his father, the Russian poet Arseni Tarkovsky.4

In 1974 Tarkovsky produced an autobiographical film a la Fellini’s Amarcord (1973), entitled Zerkalo (Mirror), which was criticized as being labyrinth in form and parabolic in nature. In 1976, he directed an acclaimed stage version of Hamlet in Moscow. Late in the decade, Tarkovsky made Stalker (1979), an ambiguous allegory of decay shot in Estonia which was read by some as an indictment of the Soviet government’s repression of intellectual freedom. It is an eerily dismal film about a writer and a scientist who are guided by a man called the Stalker, on a journey through a mysterious wasteland referred to as the “Zone.” Their goal being to travel to a place called the “Room” where all wishes may be granted, but they fail in their quest through lack of will power. In 1982, he began shooting Nostalghia (1982) in Italy for Gaumont and RAI, with Soviet cooperation.5 In 1985, he completed his final film, the international co-production The Sacrifice (1986) in Sweden.6

Tarkovsky’s Mirror is a philosophically personal and autobiographical film dealing with memory and temporality. The concepts of time and remembrance have been the tropes of investigations by other authors; for instance, Alain Resnais’ Muriel (1963) is a personal film that explores such issues through the socially changing framework of French history (circa 1960). Tarkovsky’s Mirror, alternatively titled Mirror or A White, White Day, delves into the personal histories of its characters through a kaleidoscopic mesh of interwoven time periods. In Mirror, history becomes an enigmatic Mirror that reflects three different levels of temporality in which time expresses a sense of universal oneness. There are three distinctive periods that differentiate time from an otherwise unified portrayal of the personal history of its principal protagonist, Alexei, the narrator (voice-over), who is glimpsed only the end of the film:

1) the ‘present’ circa 1975,

2) the ‘past’ of post-WWII (mid-1940s),

3) and another ‘past’ of pre-WWII (1930s).

In Mirror Tarkovsky differentiates history into temporal categories and integrates within them the personal histories of the characters to expose the unifying aspects of time. He captures a temporal oneness through a sensibly oneiric cinematography and carefully structured mise-en-scéne, especially in its color tones, surface textures, and sound designs. Moreover, he matches stock footage from these periods with the time sensibility of his own shots, that is, he cuts documentary footage with the time-image_s emerging out from his _time-pressure editing. This type of time-thrust cutting, which he used to make his thesis film The Steamroller and the Violin (1960) is in contrast to the Soviet montage style developed by Sergei Eisenstein. This new way of conceptualizing montage involves the matching of the internal rhythms within the shots with each other, and it is this new brand of temporal linkage that dictates the cut (not the concept which dictates the cut in Eisensteinian montage). These inner rhythms are related to the flow of time, the direct perception of time that exists and emanates from the shots; and as with any dynamic continuum, the flow of time carries a temporal mass or momentum, definable by a so-called “time-pressure,” a hypothetical concept in Tarkovsky’s montage theory of Sculpting in Time.7

Tarkovsky explains that editing cannot be the dominant structural element of a film, as the protagonists of Soviet montage cinema (Kuleshov and Eisenstein) maintained in the 1920’s. The film image comes into being during shooting, and exists within the frame. As Donato Totaro explains, editing brings together shots which are already filled with time (1992, 24). The function of editing is to organize the time-image_s into a wave structure inherent to film, that is, the _time-pressure wave. Tarkovsky’s concept of time-pressure is like a meteorological time-front that propagates from shot-to-shot and throughout the film, or a cardiopulmonary time-pulse that thrust against the arterial walls of the scenes, bringing temporal oxygenation to the shots and overall meaning to the film-form.

In Tarkovsky’s view, the Eisensteinian theoretical structure of the montage of attraction, as a form of editing that brings together two concepts and generates a new, third one, cannot fully explain the nature of cinema. This view is akin to the inconsistencies that exist in Newton’s law of motions (analogous to Eisenstein’s laws of montage) in explaining why light bends around the sun or in predicting the perihelion shift of the orbit of Mercury. Even though Tarkovsky has great admiration for Eisenstein’s pioneering efforts, the traditional Soviet montage cinema can only be a subset of a more encompassing grand unified theory of film. Tarkovsky’s theory derives from the incomplete understanding of time that exists in Eisenstein’s theory (whose temporal concepts are very similar to the indirect perception and treatment of time in Newtonian physics). Tarkovsky hypothesizes that time can be directly perceived in film. He theorizes that the time-thrust (temporal force or energy) is equivalent to the cinematic material (filmic matter projected on the screen at the speed of light – analogous to E = MC2) and therefore it is inherent to every shot. Therefore, just as Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity reduces to Newton’s gravitational law of force, as the material velocity becomes very much smaller than the speed of light; so too does Tarkovsky’s theory of time-rhythm montage (or Sculpting in Time) reduces to Eisenstein’s theory of shot-concept montage, as the division of the sensory-motor link becomes much more rational than irrational. Tarkovsky believed that film’s ultimate goal cannot be the interplay of concepts because the film-image, specifically the time-image, is tied to the concreteness of time and the temporality of matter, reaching out along mysterious paths to regions beyond infinity. For this reason, the poetics of cinema, a mixture of base, everyday material substances, is very much resistant to symbolism (in the Tarkovskian sense).

Even though Tarkovsky and Eisenstein appear to have opposite views on the idea of montage, Sculpting in Time incorporates some of Eisenstein’s montage categories (rhythmic, tonal and overtonal) into its own system of cutting. Eisenstein’s film structure can be described as an organic form with artificial content while Tarkovsky’s approach is organic in body, exhibiting the characteristics of a living organism, and thus, it is essentially natural. Tarkovskian time-rhythm montage is no more than the natural time variant of the unification of the shots that exists in the material of the film. It allows the separate scenes and shots to come together spontaneously, joining up according to their own intrinsic pattern of relationships and articulations. Retroactively, a self-generating structure forms during editing because of the inherent material temporality that is caught during shooting. The grouping of the shots creates the structure of a film, but not necessarily its rhythm. In a brilliant occasion of praxis aligning with theory, Tarkovsky writes: “The distinctive time running through the shots makes the rhythm…rhythm is not determined by the length of the edited pieces, but by the pressure of the time that runs through them (1986, 117).

The flow of time running through the shots creates the rhythm of the film. Moreover, rhythm is determined not by the length of the shots, but by the pressure of the time that runs through them. Therefore, montage can only be a feature of style because it cannot create this time-rhythm, the truly dominant element of our modern cinema.

Flowing systems permeate all aspects of life, matter, energy and time; but they manifest their myriad rhythms in a contradictory duality of nature, exhibiting particle-wave characteristics. On the microscopic level, nature behaves as a matter-wave whose motion is described by a matrix energy operator, H, operating on a particle-wave function, within the dynamics of the Hamiltonian representation where time is effectively stationary at the moment of the measurement, or within the Schrodinger representation where time evolves along with the moving matter, through the operations of a 2nd order space differential operator. A finely exquisite understanding of elementary quantum physics offers a penetrative insight in the Tarkovskian theory of time-pressure. The material duality of time [in Einstein’s general theory of relativity, time (t) is an equivalent coordinate to those of space (x, y, z), where all four quantities are expressible as a single 4-vector in space-time (x, y, z, t)]. The implication is tremendous because time behaves much like a light-wave that never stops moving, but also as a particle-wave that can be relatively arrested (an implication that allows for the direct perception of time in Tarkovsky’s cinema). It is not surprising that a cinematic physics exists which leads us to ask questions such as: “what is a time-thrust and/or time-pressure?” In response to this question, Totaro replies, simply, that it is the use of nature in cinema that guides and gauges the degrees of temporality of the audiovisual presentations and since nature exhibits an immense repertoire of all kinds of activities [water, fire, rain, mud, snow, wind, and even milk (just to name a few)], they become propagators of time-image_s in which the flow of time is perceived directly through a _time-thrust or time-pressure.8 The use of nature in film is purely organic and has a sense of circularity, akin to certain Eastern philosophies which, like Buddhism, are characterized by non-linear forms of thinking; for example parallelistic logic, where A is equal to not A, is in marked opposition to Aristotelian logic where A can never equal not A.

Time dictates the particular cutting strategies because it is imprinted in the frame. The shots that won’t edit or properly join, are pieces that record different kinds of time; implying that actual time cannot be joined with conceptual time. The temporal consistency that propagates through the shot is defined as its rhythmic intensity (or “sloppiness”). It follows from cinematic physics that editing is the assembly of the shots which results from the time-impedance matching (analogous to the impedance matching characteristics of filters used in electronic circuitry) of their inherent time-pressure_s. In short, to make a Tarkovskian film is to maintain the operative _time-pressure (or “thrust”) that unifies the impact of radically different shots.

How does time-pressure makes itself felt in a shot? To paraphrase Tarkovsky with a Deleuzian twist, time materializes when there is a feeling of something significant and truthful that goes beyond the optical and sound situations on the screen. The audiovisual events depicted on the screen are merely material indicators of something stretching out beyond the infinity of the image (in electromagnetic field theory, the light wave’s potential becomes zero only at infinity) – what Tarkovsky calls “pointers to life.” Thus, a truly real film stretches beyond the boundaries of its sound-images, creating more thoughts, ideas, than consciously put there by the filmmaker. It does so by recording on film the time-waves which flow beyond the edges of the frame; and like time’s dual nature (particle-wave), the dominant factor in Tarkovskian cinema is a dual or two-way process in which a real film lives within time only if time lives within it. A ‘real’ film is like a living organism because it grows in form and meaning after leaving the editing bench, detaching itself from authorial intent and allowing itself to be experienced and interpreted in individually personalized ways – just as those unique and precious moments in real life.

This is a radical movement in modern cinema because it liberates film from the constraints of the author who creates it, allowing the film to live in time on its own.9 Ian Christie discusses the issues of formalism and neo-formalism in the modern cinema:

Formalism, they [David Bordwell & Kristin Thompson] believe, unlike some structuralist and psychoanalytical methodologies, crucially implies an active spectator … Bordwell proposes a ‘constructivist’ theory which links perception [Tarkovsky] and cognition [Deleuze] … Both Thompson and Bordwell make use of the term ‘parametric cinema’, adapted from Burch (1973) to take their neo-formalist analyses into challenging terrain … defined as the foregrounding of an artistic motivation in a systematic, structuring fashion … it was not until the 1980s that … the long-neglected work of Mikhail Bakhtin …Bakhtin’s most influential concept is probably ‘dialogism’, which emerged particularly from his study of Dostoevsky’s novels … involves distinguishing between an author’s direct speech and that of his characters, which can approach the relationship between two sides in a dialogue … two of Bakhtin’s other contributions seem even more pertinent to cinema …Bakhtin showed how these (i.e. ‘speech genres’) interact with literary genres to define a ‘genre memory’ [Tarkovsky] which sets limits to each genre … This term (i.e. ‘chronotype’), taken from mathematics, is used by Bakhtin (1981) to refer to the specific interrelationship of time and space in different forms of narrative … Maya Turovskaya (1989) has used the concept of the chronotope to illuminate Andrei Tarkovsky’s idea of cinema as ‘imprinted time’.10

Tarkovsky strictly applies time-thrust editing theory to the minute details of his films and achieves a separation between authorial intent and spectator participation. Films such as Solaris and Mirror tap into the time-memory elements of the viewers’ personal histories, allowing each individual to develop his or her variant forms of understanding to what he or she perceives.

Tarkovsky’s theoria appears to be a complicated cinematic construct but it is not.11 What is difficult about Tarkovsky’s cinema is its praxis. It is not easy to identify the proper time-image match which is necessary to maintain the desired stability of the time-pressure level between shots. In short, it is imperative that the time-wave propagates freely from shot-to-shot, otherwise, a form of resistance develops in the “gap” and the purity of the optical and sound situations which is the basis for the direct perception of time is lost.

Gilles Deleuze discusses the significance of this “breach” in the sensory-motor linkage:

bq.… from its first appearance, something different happens in what is called modern cinema … the sensory-motor schema is no longer in operation, but at the same time it is not overtaken or overcome. It is shattered from the inside … perceptions and actions ceased to be linked together, and spaces are now neither coordinated nor filled [ i.e. “gaps”] … It is here [in the “gaps”] that the reversal [where sign and image transposed their relation] is produced: movement is no longer simply aberrant, aberration is now valid in itself and designates time as its cause …. It is no longer time that depends on movement; it is aberrant movement that depends on time.12

The stationary relation of the sensor-motor link and the indirect image of time is transformed to a delocalized relation of the pure optical and sound situations and the direct image of time.13

Deleuze writes about Tarkovsky’s text of the ‘cinematographic figure’ as follows:

…Tarkovsky says that what is essential is the way time flows in the shot, its tension [i.e. time-pressure] or rarefaction, ‘the pressure of time in the shot’. He appears to subscribe to the classical alternative, shot or montage, and to opt strongly for the shot (the ‘cinematographic figure’ only exists inside the shot). But this is only a superficial appearance, because the force or pressure of time goes outside the limits of the shot, and montage itself works and lives in time …. Tarkovsky calls his text ‘On the cinematographic figure’, because he calls figure that which expresses the ‘typical’, but expresses it in a pure singularity, something unique. This is the sign, it is the very function of the sign … It is only when the sign opens directly on to time, when time provides the signaletic material itself, that the type [cinematographic figure => ‘typical’], which has become temporal, coincides with the feature of singularity separated from its motor associations. It is here that Tarkovsky’s wish [a reference to Stalker] comes true: that ‘ the cinematographer succeeds in fixing time in its indices [in its signs] perceptible by the senses [my italics].’”14

In short, modern film is not a language operating with predefined cinematic units (unit-shot = montage-cell) and montage is not a super-unitary system that organizes sub-unit shots.15

The time-thrust can be easily overlooked because they are often unperceivable optical and sound situations, with no commensurable links to each other and no easily inferable connections to conventional referents.16 For example, Mirror is structured by the interposition of personal memories within a timeline of significant historical events and socio-cultural situations. Tarkovsky’s style of cutting tends to keep the historical temporalities separate, but now and then, he allows them to co-exist in the same diegetic space and sometimes in the same shot. In Mirror, the act of remembering alternates between two worlds, one actual and the other virtual, and sometimes, memory exist simultaneously in both worlds. The memory-scape bifurcates into actual and virtual situations that parallel each other within a temporal quandary.17

Mirror extracts images from thought-memories and surrounds them in a world of time. Material objects are reflected in a Mirror-image (time-image) as a double movement of liberation and capture, where the virtual object Mirror_s the real; as if, momentarily, the image in a _Mirror separates from its surface and crystallizes into physicality, only to reabsorb again and become mentality. In short, the time-image has an image-structure, a coalescence of the actual and the virtual. Donato Totaro explains that the physicality relates to matter as an extension of space and to the movement-image, while the mentality is tied into memory as a duration of thought and the time-image. The movement-image is a spatialized cinema, as seen in Hollywood genre films, where time is measured by movement and determined by action. The time-image is a temporalized cinema, as in the European art films, where the temporal links between shots are non-rational and incommensurable, resulting in the emergence of empty, disconnected spaces; what Deleuze calls “any-space-whatevers.”18 Totaro correlates Bergson’s views on memory19 with another form of the time-image concept:

The crystal-image, which forms the cornerstone of Deleuze’s time-image, is a shot that fuses the pastness of the recorded event with the presentness of its viewing. The crystal-image is the indivisible unity of the virtual image and the actual image … The crystal-image shapes time as a constant two-way Mirror [like in Mirror] that splits the present into two heterogeneous directions, “one of which is launched towards the future while the other falls into the past. Time consists of this split, and it is … time, that we see in the crystal [the crystal of Mirror]” (Deleuze’s Cinema 2, pp. 81).20

The significance of the crystal-image is of immense importance in Tarkovsky’s theory of time-pressure and in the time-rhythm montage of Mirror because it is the key that unlocks the door to the compositional domains of the opsigns and sonsigns which are the correlates of the time-images. Totaro writes that:

Deleuze uses the crystal-image as an aesthetic rather than purely theoretical tool by ascribing stylistic qualities to it [film style => philosophy] … Deleuze does not subscribe, as does Tarkovsky, to the notion that the long take, or time registered in the shot, is of a different value or type than time registered through montage (Eisenstein) … this is a superficial distinction because, “the force or pressure of time goes outside the limits of the shot, and montage itself works and lives in time” (Deleuze’s Cinema 2, 42).21

If one compares film with music, cinema stands out as giving time visible, real form. A piece of music can be played in different ways where musical time is a condition of certain causes and effects set out in a given order, carrying abstract and philosophical sensibilities – music records time inwardly. But film is able to record time outwardly with visible signs, recognizable to the senses – so time becomes the very foundation of cinema, as sound is in music, color in painting, character in drama. Rhythm is not the metrical sequences of the shots but the time-thrust within the frames. What is different about Tarkovsky’s editing is that it brings together time, imprinted in the segments of film. Cutting does not engender, or recreate, a new quality; but it brings out a quality already inherent in the frame that it joins. Editing has to do with temporal extensions and the degree of intensity with which these _time-thrust_s possess (_time-pressure_s). Editing represents intervals of time dealing with the diversity of life perceived. Rhythm exists in the life of the object visibly recorded in the frame while the temporal movement is conveyed by the flow of the life-process in the shot. It is through this time-rhythm that the director reveals his individuality and stylistic marks. Time-rhythms come into being spontaneously during shooting, with the filmmaker’s sensibility for nature’s rhythms in his search for these elusive _time-image_s. Tarkovsky’s editing style disturbs the passage of time by introducing time-flow interruptions (the act of cutting) which create temporal distortions. It is the distortion of time that gives it rhythmical expression.

This is the basis for Tarkovsky’s theory of Sculpting in Time. It exposes the direct figure of time by the deliberate and careful joining of shots of uneven time-pressure. The cutting has to come from the inner necessity (within the shot) and the organic process going on in the material as a whole (akin to Eisenstein’s overtonal montage). The process of joining segments of unequal time-value breaks the time-rhythm. However, if the temporal disjunctions are correlated by the _time-thrust_s (forces or pressures) within the assembled frames, then the desired rhythmic design can be achieved. As Totaro notes:

Matching shots of differing rhythms can be done without destroying this organicprocess if it grows out of an inner necessity. An example is the car journey sequence in Solaris. Through camera movement, sound and consistent forward direction the shots in this sequence share the same rhythm. The montage heightens to a frenzied single-frame fusion of overlapping highways, lights, skyscrapers and cars. This technological symphony is abruptly followed by a cut to astronaut Kelvin’s childhood dacha. The image is quiet, peaceful and serene. The time-pressure in this shot is opposite from that in the previous shots. …This is one of the few examples of Tarkovsky using expressionistic editing and deliberately matching shots of differing time-pressure_s. But the cut is theoretically justified because the stark contrast between the chaotic _time-pressure in the technological montage and the tranquil rhythm in the shot of the natural landscape reflects one of the film’s thematic conflicts of technology/nature, space/earth (1992, 24-25).

Tarkovsky’s sense of time is related to his innate perception of nature. His editing style is dictated by the rhythmic pressures in the segments of film. His authorial signature comes from his editing style and is the mark of his attitudes to the conception of cinema and philosophy of life. His art films are formed by organic processes and are living organisms with their own circulatory system (time flow) which must not be brought to stasis. Tarkovsky’s time-pressure montage represents the sensibility of an auteur, his film style, and personal philosophy. Tarkovsky’s films form a cinema of thought-images.

Mirror is a direct image of time created by a flux of thought-images (or thought-waves) propagating in the time-memory universe of Alexei’s mind. The film reflects the real life recollections and habitual memories of an existing person (Alexei as Tarkovsky’s persona) in relation to his family. It also Mirror_s the pure recollections associated with Alexei’s past, and especially, the involuntary recollections and virtual memories of his childhood dreams and fantasies. _Mirror is a personal and self-revealing film with autobiographical characteristics that correlate private and collective memories. Tarkovsky did this by reconstructing the country house where he grew up, a beautiful wooden cottage located adjacent to a field of buckwheat, as well as using old photographs, visual recollections, etc. Tarkovsky sets up the story in a dacha specifically to evoke/recreate the time-memory elements of his childhood. The re-constructed house of Tarkovsky’s childhood, set against a buckwheat field backdrop, recreates a personal history that is both real and imaginary; and where there is no distinct separation between interior and exterior spaces. To underscore this autobiographical palimpsest, Tarkovsky gets his father, the acclaimed Russian poet Arseni Tarkovsky, to recite his poetry at several points during the film. He cast both his real mother, Maria Tarkovskaya, for the part of Alexei’s mother as an old woman and his 2nd wife, Larissa Tarkovskaya, who plays the role of the doctor’s wife in the “earring scene.”

Mirror is a dream-memory unfolding within the narrator Alexei’s personal history. It functions overtonally (Eisenstein’s overtonal montage) as a single, unified memory-image within a history fragmented in time. Tarkovsky’s execution of the shots orchestrates a kinesthetic intensity of an overtonal time-pressure that propagates from shot-to-shot throughout the entire film. There is a unified, temporal feel to the film that makes the objects and events look real and virtual at the same time; in short, they become crystal-images. The overtonal qualities of Tarkovsky’s compositions go beyond those of Eisenstein’s juxtaposition of stationary shots because they achieve a greater dynamic range of temporal timbre. When Tarkovsky organizes the various cinematic elements of the film, he allows different aspects of time to interact with each other; for instance, he treats the mobility of the tracking camera with regards to the movement within the shot and the temporal chromaticity of the image. In effect, the camera interacts with the time-thrust that pierces through the frame-to-frame structure of the shot, evoking emotionally visceral responses from the viewer rather than conceptual attitudes about history and society. Tarkovsky presents a Möbius strip of distressingly nostalgic periods in the USSR (Russian & world histories), filtered through Alexei’s personal history. For example, the documentary archival footage (found film segments) of the Red Army crossing Lake Sivash (called the “Putrid Sea”), of the refugees exiled in the Soviet Union from a savage Civil War in Spain, and of the Chinese Maoists waving their little red books, are all actual facts with historically significant moments which are estranged and rendered oblique, by a combination of film overexposure and frame acceleration, into an all encompassing, non-distorted subjective time-image.

Tarkovsky’s intermixing of chronologically ordered stock footage with non-chronological personal histories further wrench the linearity of the temporal events. These found film segments move forward in time, from an atmospheric balloon journey undertaken by a Kurdish aviator in 1937 to the Soviet-Chinese conflict of the 1960s; while the personal histories gallop back-and-forth through the time-memory mesh, where time is no longer linear nor linked.

Tarkovsky creates these disruptions in time by breaching the feeling of its normal rhythms. The sense of time’s universality is violated by personal memories that penetrate into past histories, creating ripples through the fabric of time. A sense of virtuality parallels one of actuality, and what is most personal becomes time-like and most universal. In effect, Mirror breaches the movement-image structure by implanting a time-image mesh (a mesh => “gaps”) at the heart of an infraction in the steady flow of time. The temporal disruptions result from the mélange of personal histories and time-memory elements that maintain the time-pressure differential between shots, sometimes moving into flashbacks and sometimes into dreams.

It is the attention to this kind of editing detail that gives Mirror its feeling of being real, even though, the film is not realism because it is effectively a mental construct, made by re-constructing nature into a memory-scape. Tarkovsky gives us a taste of the different flavors of memory that time carries along in the film. They are a mix of pure perception, pure recollection and involuntary memory which he interweaves in the historical fabric of the private lives of its characters. In effect, the habitual forms of actual memory are intermixed with the much large set of virtual memories which comprises almost everything else that someone can think and/or dream about. In Mirror, the interpenetration of present realities (circa 1975) with past memories (1930s and mid-40s) creates a perplexity about the juxtaposition of non-chronological fragments, stressing the indivisibility of time and the infinite possibility of a perception that journeys beyond the borders of the screen. Tarkovsky achieves a sense of temporal unity through the confusion between ontological states, an inseparable feeling of being in a here-and-now simultaneously with a there-and-then, in short, a sense of not being so much in the present but more in the past. Cinematically, he accomplishes this feat of “mystical realism” by sometimes using variable slow motion shots, with slowly creeping lateral tracks or pans, which achieve the effects of molding time by capturing the subtle details of certain sound and image events that exist in nature. These are the pure optical and sonic situations that trigger the avalanche of virtual memories, _time-image_s, including sound-images, which ripple through this inseparable weave of time. They mold the temporal momentum or mass that flows in all of Tarkovsky’s films.

Tarkovsky’s time-rhythm montage creates dreamlike imagery that resists the spectator’s need for logic and credibility. An oneiric liquidity flows through not only Mirror, but most if not all of his films. These films achieve a kinesthetic feeling of time through the sensory-motor link that they continuously disrupt. Dialogue and audiovisuals are combined to convey daydreams and time-memories about the past, present and future. Tarkovsky unveils time directly to his audience by capturing the time-rhythms within the consecutive frames of the shot and matching them with the time-images in a series of shots. As the analysis will demonstrate, Tarkovsky does so in basically two ways, one by the continuous movement of the camera through space and the other by not controlling the viewer’s attention by cutting from one image to the next; all of which emphasizes the temporal nature of reality.

There is no better way to show Tarkovsky’s style of editing (time sculpting) than to examine the details of the optical and sound situations which he develops in Mirror, so I would now like to illustrate some of these strategies of time-pressure at work with the following close textual analysis. To supplement my analysis of Tarkovsky’s theory of time-pressure in Mirror, a partial scene/shot breakdown with detailed audiovisual description has been included as an appendix at the end of this work. I will look closely at the first shots of the pre-credit scene and the first 22 shots of the opening sequences of the film.

The pre-credit opening scene of Mirror is unique because it precedes the credits and involves two shots, one relatively short (20”) as compared a very long one (3’38”). Moreover, it is filmed in a documentary style and viewed on a television screen by an adolescent boy. The sense of authenticity is carried throughout the film with precise insertions of found historical film segments. This editing strategy is part of the overall narrative because it sets an emotional tone rather intellectual one. The stuttering of the teenager hints at the fragmentation of the spoken language and to the fractured representation of the self as written subject. There is hope in this film because in the prologue the stuttering is hypnotically suppressed when the teenager says: “I can speak.” This event announces the emotional emancipation of the filmmaker through his characters. The longing for freedom is at the heart of Mirror as is the fear of loosing it, because hypnosis can never be a cure to stuttering (am emotional problem reflected through language).

Documentary realism, boom shadow and all.

Mirror reflects an apprehension of childhood and its memory-image_s which coexist with the narrator’s (Alexei => Tarkovsky) present state of mind and real situation. The _time-thrusts reflect the forces of memory that reside in the mind-brain where they can continually renew themselves in the present moment, allowing the perception of time to become like a taut string or sheet, sustaining a tension between present and past that creates a broken representation of the individual, as represented by the stuttering subject in the pre-credit sequence of the film (a unusual montage strategy).

The opening of Mirror is also unique because it straight-cuts to a long take (45”) of the buckwheat field in the background (one of Tarkovsky’s childhood memories) and a young woman (Alexei’s mother) in long shot, sitting side saddle on a wooden fence rail, smoking a cigarette and facing the field while apparently looking at some thing moving in the far distance. It is the combination of the long take and the unusual mobility of the camera that pulls out the time-pressure from this shot. Specifically, the camera tracks forward slowly toward the back of the woman, favoring neither her nor the expansive field in the background, hesitating on her, but then moving past her to the man in the extreme background. By not cutting into the continuity of time, it is able to further register the direct feeling of time as it moves forward, passing her on its way into a view of the field and the mysterious point of interest, the stranger (passer-by).

This first post-credit scene (shots: 1 – 11) in Mirror is important because it is the all pervasive crystal-image that carries the force of the time-memory through the entire film. It is where the flow of time is most directly perceived. It is representative of the time-thrust that propagates through the film, enabling the linkage of past (film’s beginning) and present (film’s ending) to be achieved through a process of memory renewal in the present (Alexei’s childhood memories). The strong physical nature of the mighty gust of wind that waves through the field as the man stands in it, feeling its thrust against his whole body, is the epitome of the crystal-image in this film; and by not cutting into these shots (shots: 7, 8 and 9; especially shot 7) and letting flow freely as time-images, Tarkovsky achieves artistic emancipation, demonstrating his style of editing as the process of sculpting in time.

The use of nature’s time flow, especially the ‘wind’ in this opening scene, is of prime importance in Mirror. Tarkovsky sets up the story in a dacha specifically to evoke/recreate the time-memory elements of his childhood. He did so by using old photographs, visual recollections, etc., to reconstruct the country house where he grew up, a beautiful wooden cottage located adjacent to a field of buckwheat. It is the ‘tonal intensity’ (Eisenstein’s tonal montage) of this time-image, the sloppiness of the sound-image of the wind blowing through the buckwheat field, that creates the pure optical and sound situations through which the time-pressure propagates. This “dacha-buckwheat-wind” time-image is a prime example of a modern theory of cinema. Tarkovsky’s neo-formal theory of sculpting in time integrates earlier elements from Eisenstein formal theory and then goes on to re-theorizing about the essential nature of cinema. It redefines the cinematic unit in terms of time, shifting emphasis from the shot-montage to the time-rhythm.

The third scene (shots: 12 – 15) is also important because it enters into the childhood home. The “dacha” is the predominant chronotope of Mirror. It is the intrinsic connection that links the temporal and spatial relationships presented in the film whose polyphonic nature is expressed in the last sequence where the blending of space and time occurs as the past merges with the present, expressing the indivisible unity of time.

The fourth scene (shots: 16 – 18) is crucial to the narrative push because it brings to mind the chronotopes of the dream-memories that seems to take place inside the dacha but differ from the color memory-images that appear in the previous scene. Here, they occur in monochrome and seem to be slowed down. The shadowy images (both optical and sound) of the bedroom where the little boy (young Alexei) sleeps are flattened without much depth, but as opposed to the room of the dacha in the last scene, it is richly decorated and cluttered; and the sounds are displaced to the interior planes of consciousness, creating a strange feeling of dislocation that occurs in dreams. There is another strange dream-chronotope later in the film, that is, the woman’s levitation which takes place in another non-identifiable space, similar to the space of young Alexei’s bedroom.

These scenes demonstrate how Tarkovsky succeeds in suppressing the dramatic meaning in the optical and sound situations and allows a temporal meaning to float from beneath the narrative and come from beyond the image. The filmic features that he presents show evidence of bizarre mind states produced by quasi-dreaming and pseudo-remembering. An analogue of reality is presented where peripheral vision is blurred and light comes alive with pulsating changes in chromatic tonality. It is a virtual reality where space and time are discontinuous and matter (fire, wind, water) moves with a graceful force (time-thrust).

The fifth scene (shots: 19-20) seems to carry with it the dislocation and strangeness of both space and time that appeared in the previous scene. Here, the plaster on the ceiling of a not so easily identifiable room begins to disintegrate, falling in slow motion onto a spatial position previously occupied by the young woman with wet hair. The feeling is kinesthetic because the oneiric force of the time-thrust seems to transcend space and time, allowing the audience to feel the physicality of this virtual event. Moreover, this unique cinematic presentation appears to suppress (as in the case of the stuttering teenager) any psychoanalytical interpretation in favor of the actual experience of this oneiric mood. Mirror is a mood film at heart.

The sixth scene and the last one of real interest in the scene/shot breakdown (shots: 21 – 22) breaks the standard belief in the idea of editing, that is, the linkage of identifiable shots into a scene (Hitchcock and others have used such a device before Mirror). There is an apparent hidden cut in shot 21 that results from a camera pan across the image of the young woman who is looking at herself in the Mirror, to a blackened screen, and then the pan continues to another space and a different time (the present) where an older woman (Alexei’s mother) is seen simultaneously as an actual (physical) and virtual (memory) image existing as the reflection off the surface of a Mirror (crystal-image). The significance of the Mirror motif occurs here as it did earlier when the young woman looks into a clouded Mirror and sees herself as an older woman (played by Tarkovsky’s real mother, Maria Tarkovskaya). Tarkovsky’s greatest achievement in film is to make this homage to his “mom” as a dream-memory of a time-image that is reflected in a Mirror. This is the deepest emotional expression and form of love that a son can do for his mother, and such is the work of art known as Zerkalo (Mirror).

APPENDIX

A partial scene/shot breakdown of Mirror: with detailed audiovisual description and shot length in minutes (’) & seconds (’‘):

PRE–CREDIT OPENING SCENE:

1. The film begins in color with a straight cut into a shot of a young boy positioned in front of the screen of a television set, as we hear: “What is your name? My name is Yuri Zhary.” (20”)

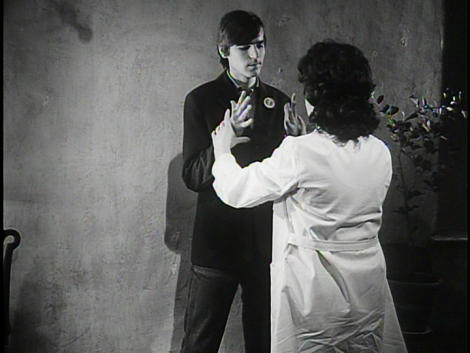

2. A straight cut to a long shot of a woman psychologist who is using hypnosis on a eenage boy to cure him of a severe stuttering problem. (3’38”)

3. A straight cut to a black screen with white lettering giving the film’s title – ‘The Looking Glass’ (5”). A straight cut to the other film credits

OPENING:

A straight cut back to the film’s title – ‘The Looking Glass’ (6”)

SCENE 2. EXTERIOR – DAY – BUCKWHEAT FIELD:

1. A straight cut of a woman in long shot, sitting side saddle on an old wooden fence, smoking a cigarette and facing opposite camera toward a huge buckwheat field in the background. She is wearing a white dress with a dark sweater. Her hair is blond like yellow straw. The color texture of the landscape is bluish green. The camera slowly tracks forward toward her to a point where it almost stops, framing the woman in a medium shot filling one third of the frame, in conjunction with the sound of a train whistle and the start of the voice-over (the narrator is Alexei). The camera’s determined forward movement passes to the right of the woman, leaving her image to disappear off-screen left, and moves to the edge of the field on an extreme long shot of the very small image of a man, standing in the middle of the field and within the near-center of the screen. (45”)

2. A straight cut to the woman in right profile and close-up (shoulder shot), still smoking passively. She turns her head toward the camera and directly stares into the lens for about two seconds. The color of her face glows with a golden yellow light. The camera pans slowly to the right, rack focuses to some bushes where green leaves and branches rustle in the wind. (18”)

3. A straight cut follows again to the woman in long shot, sitting on the fence but viewed from a slightly different perspective. The camera seems to pan-and-track in a slight circle path about her in a movement to the right. (16”)

4. A straight cut back to the man in long shot is made as he makes his way to the edge of the field. The camera leaves him and begins to pan left with a slight tilt down toward the woman on the fence. It continues its movement with a track that circles around her, to a position behind her back, where it turns to view the woman against the background of the buckwheat field as she blows smoke in the wind (similar camera POV as in shot 1). The landscape is bluish green but the characters’ faces are luminescent with red, orange and yellow colors. The man arrives in front of the woman whose back is facing the camera and after a slight pause, she turns around to look back as though she is going to stare into the lens again (as in shot 2), but her gaze penetrates beyond the camera. (1’33”)

5. A straight cut to two young boys in long shot, laying stretched out in a hammock and facing each other. This stringed up hanging bed looks like a huge spider web spread out between two trees. The children appear to be sleeping. (3”)

6. A straight cut is made back to the man and woman in long shot but from a different perspective. The man is at an arm’s length near her as she sits on the edge of the wooden rail of the fence which is seen in oblique relative to the bottom of the screen, while a row of bushes is seen in the middle ground with the buckwheat filled in the background. The man is also smoking a cigarette. He sits down next to her, his weight causing the wood to snap and they both fall to the ground. The camera tilts down and dollies toward the man, then follows him as he gets up. The camera now captures them in a two-shot, as they brush themselves off. The camera pans right with the man as he continues to talk, then back to the left as he walks back past the camera and exits frame left. The camera now frames the woman in a medium shot looking in a direction over the top of the camera toward the man’s off-screen voice. (2’00”)

7. A straight cut to the man in very long shot at the edge of the field (similar to shot 4). He begins to move away as we hear the sound of a dog barking in the distance. A silent sound segment follows for a few seconds; and then a huge wave of air (a strong feeling of the force of the wind exists here) moves across the field, from the right background and up to the foreground at the edge of the screen. We can see the pressure of the air against his body. The man stands still for a moment after the wind dies down. A golden streak of color stripes the middle portion of the bluish green field. (36”)

8. A straight cut to the woman in medium close-up looking obliquely left and slightly down. She is viewed in front of a mid-ground row of trees that hide a clearing, probably another portion of the field, that separates the forest background in the distance. A similar wave of air that comes and goes, but reduced in intensity, produces a gust of wind that strikes her body with a kinesthetic pressure, as she turns and moves screen right. (7”)

9. A straight cut back to the man in very long shot in the field is made as he walks away. Another strong gust of wind passes through the field, causing the man to stop momentarily and turn to look back at the woman. The man hesitates in an estranged, bizarre manner as he begins to lift his hand as though he is going to wave goodbye or do something else to call attention, but never completes his intention and turns back around and walks away. (18”)

10. A straight cut back to the woman in medium close-up (similar to shot 8) looking obliquely left. There is no wind this time as the voice-over begins to recite a poem from the poetry of Arseni Tarkovsky. The camera pans with the movement of the woman who is heading screen right and begins to track her from behind as she moves up to the dacha. She reaches a point near a tree when an object falls off outside the edge of one of the dacha’s windowsills, causing her to turn suddenly toward the camera as though she is again going to stare into the lens. (27”)

11. A straight cut to a little boy (maybe Alexei) standing in medium shot. A fire in an outside stove with its door opened is seen behind the boy, a pot appears to be on top boiling a liquid into the air. The boy looks slightly down at the camera and then turns his head to look screen left. He turns it back to a point where he is looking right and down as he still holds the same footing position; and then he begins to walk screen right. He passes by a youngster (boy or girl) with a shaven head who is laying flat on the ground and on his or her belly, sticking three quarter the way out of a dog house, where a little puppy is seen playing near the child’s head at the bottom edge of the screen. An apparently different woman dressed in a long dark skirt and dark sweater moves into frame from screen left, grabs a jacket on top of the dog house, and picks up the child as they move off screen right. (15”)

SCENE 3: INTERIOR/EXTERIOR – DAY – DACHA:

12. A straight cut to a pair of hands in medium close-up, holding a spoon and stirring up something in a bowl is seen as some spilled milk puddles to the left side of the screen on top of the table where a cat is lapping the white liquid. After a moment, we see that there are two little children both with heads shaven, one who is spooning a substance (probably milk) out of the bowl, the other who is fooling around by pouring either a white powder (probably flour) on top of the cat’s head. The voice-over continues to recite Arseni Tarkovky’s poem. The camera moves to the right and away from the kids to a point halfway across the room where a woman is standing up alone in the corner. There is a slight pause in her position before she begins to move screen right away from the corner screen and disappears out of frame right. The camera lingers for a few seconds on the corner she previously occupied. The camera picks her image again as she heads to a window, near another corner on the opposite side of the room, where she sits down to stare out of its opening. The camera seems to pause for a moment on the woman whose hair is blonde, as it continues a tracking movement past the woman, swinging rightward in the process, to capture a full frame view of the outside backyard of the dacha where it is raining. We cannot hear the rain but only see it as the poem is being recited. The camera pauses for a moment on a table that is located in the left foreground of the screen, supporting unknown objects on its wet surface. A grassy open lawn area lies in the middle ground where a few scattered trees grow, partially veiling a greater forested spread in the background. The camera tilts upward revealing a semi-circular string of bushes that complete the view of the mid-ground, as we see further behind a clearing which again separates a forest background. The rain continues to fall. (1’28”)

13. A straight cut to the woman with blonde hair in medium close-up follows. She is looking obliquely right near the front of the camera. Initially, the poem continues to be spoken until there is a sound of rattling, at which time the poetry stops. The camera stares at the woman who stays immobile for a time; and then she looks right when the sound of rattling is heard. The faint cries of kittens are heard intermixed with the rattling sound. She decides to move screen right to a desk near a window where she picks up a book that she opens momentarily. As the camera pauses on the woman who remains in the shadows near the desk, she suddenly hears a ruckus; and then turns toward the camera as we hear the barking of a dog. She walks screen left past the two young children, a boy and a girl, who were at the table at the center of the room, passing another window in the background of the dacha that strongly lights up the inside of the room. As the camera tracks-and-pans her going toward the door entrance, we see in the right top corner of the screen a clock, located above a bright lit area of the wall that reveals the log-cabin structure of the dacha. She comes back to speak to the children who are seated at a table: “It’s a fire, but don’t shout.” As the children get up there is a cut on action to a reverse angle of the table. (44”).

14. The children leave the table and run toward the camera located between them and the door. The camera pans quickly left as they move out-and-away from this picnic style bench (table). As they pass behind the camera, it pulls back slightly and pans slowly right to stare at the table. As it pauses on the vacated room, we see an empty bottle (milk bottle) roll-off its surface and hit the floor, rolling away and making a hollow crystal sound. Now, the camera pans quickly leftward to reveal a bright, blurred image with a myriad of red, orange, and yellow hues and the image of a doorway with penetrating blue color streaming in from its edges. It is the door entrance of the dacha reflected in an old Mirror. The out-of-focused image of a little boy in dark shorts is seen standing facing out near its right edge. There is something brilliantly orange and yellow in the upper left corner region of the door (sun or fire). Suddenly, there is a re-focusing which seems to efface the warn-out dark spots of the Mirror, revealing another little child with lighter shorts who is standing to the left of the taller child (previously described).

The camera pauses on them for a moment, causing us to wonder if it is still a virtual Mirror image or a real focused shot of the backs of the children looking out of the doorway. It begins to move again as a ceiling oil lamp appears in our view. The camera is panning left as we hear someone shouting. Strangely, as it pans another child, a slightly older boy with dark hair and wearing a fur collar overcoat, it moves out of the shadows and screen left. The camera picks up behind him, whose face glows with a golden orange light, as they move toward the open door of the dacha that presents us with a blurred out background amidst a gentle falling rain. The camera moves through the right side of the door and past this boy, revealing in a track-and-pan motion a woman dressed with a dark heavy sweater and wearing a deep dark red dress, standing in a full shot in the front yard and looking at a burning barn. The camera continues to move left and track right as it passes to the right of a ladder positioned screen left, as we hear the sound of dripping water and see a gentle rain. The woman is now framed in the center foreground while a man stands left frame in the middle ground, as a girl dressed with a white fur collar overcoat moves into frame from the bottom edge of the screen. There is a huge blinding blaze on the left side of the screen. (59”)

15. A straight cut to the woman in medium shot and right profile, staring at the brilliant fire. Thick woods are seen in the background. She moves screen right to a well and sits on its edge, as she holds her arms crossed around her upper body as though she is hugging herself. We hear the sounds of the well bucket that is tied to a rope from an unseen support, swinging and squeaking, as it moves through the air in its pendulum motion. The man passes the woman on her right as he heads toward the fire amidst the cry-like sounds of the squeaking bucket. The camera follows the man’s movement and reveals that the fire is a building blazing out of control. It tilts up slowly as the man picks up his pace toward the burning inferno. We hear the soft roar of the combustion of the crackling wood and see the smoke clouds rising into the air which seems to blend with bluish green of the background forest. Once the man gets very close to the blaze, its heat intensity (time-pressure) is so great that he attempts to circumvent it by moving screen left. (53”)

SCENE 4: NTERIOR – NIGHT – DACHA:

16. A straight cut to shadows that slowly unveil a little boy (Alexia) lying in a bed. The image has switched to black and white. He is sleeping. We hear the fluttering hum of a flute in a form of background music, as the sound of the cry from a night creature (bird or animal) punctures the sonic space. The boy sits up and looks screen right. (21”)

17. A straight cut to the exterior of the dacha at night looking into a wooded brush area. The camera pauses for a few seconds as it slightly pulls back and tracks left to a point when a strange wind gusts through the brush. In a bizarre fashion, the weeds bend back only in a narrow path across the middle ground of the screen without disturbing the other outer surrounding foliage. Another cry of the night animal (maybe a night owl or raven) is heard in the midst of rustling noise from the wind and the eerie, celestial sound of synthesized flute (non-diegetic sound) that gives the night space an air of mystery. (17”)

18. A straight cut back to the boy sleeping in his bed (similar to shot 15). He softly cries out in his sleep: “Papa.” As he does so, there follows a ‘double cry’ from the unknown night creature that sonically sounds like the phonics of ‘Papa’. The little boy sits up as we see him from a different perspective. A bright area lies behind, a shade partially covering a lit window. He gets out of bed and moves screen right to the entrance of another room (maybe the living room) as we hear the sound of the night creature again and see a mysterious flying object moving rapidly from left-to-right across the screen (possibly a shirt, maybe the night bird?). (39”)

SCENE 5: INTERIOR – TIME OF DAY UNKNOWN – DACHA:

19. A straight cut to a left profile medium close-up of the narrator’s father, a young, shirtless man in his early thirties with dark hair, leaning forward to the left, seemingly helping a young woman, the narrator’s mother Maria, with the washing of her hair. There is a fire burning in the background. Everything is happening is a suspended slow motion. Maria appears to have dark hair but it is wet so we don’t know its true color. She is leaning forward, facing straight down into the tub of water, then she begins to pull up letting her wet hair hang down over the expanse of water. She continues to rise with her arms in a partial crucifixion position as the camera pulls back away from her. We hear again the eerie, celestial humming that seems to have grown into stormy orchestration of a ship’s bell ringing, muffled with the sounds of train wheels passing over railroad tracks – like the synthesized sounds of an oncoming storm. (53”)

20. A straight cut to an empty room (same as shot 19) and from a very slightly different perspective. The color is more sepia than before (white grayish color) as the whole room is caught in a mysterious rain storm. The ceiling is falling from the dacha’s sky, crashing in pieces onto the floor. Water is pouring out of the hole that we can’t see. A fire is seen in a Mirror screen left. The mysterious sounds of a ship’s bell and a flute or blowing air pass the open tip of a bottle are intermixed with the crashing of ceiling chunks that look like pieces of bright, white ice. (13”)

SCENE 6: INTERIOR – TIME OF DAY UNKNOWN – DACHA:

21. A straight cut to Maria (same as in shot 19) in medium shot, holding her hands on top of her wet hair as she is moving screen left. The eerie, celestial, symphonic musical hum bridges the gap between these two shots. It is raining here (as in shot 20 but not shot 19). She looks down and turns, almost looking directly into the camera, then she stops as the camera continues to move leftward, panning her face in a medium close-up. The camera continues its movement past her, coming to a Mirror which reflects the woman’s image in virtual left profile (actual right profile). It continues its cinematographic leftward pursuit until the screen is completely black. It pauses for a moment then begins moving screen left, revealing a sparkling light texture of a wall whose surface is sheeted with dripping water. THERE IS A POSSIBLE HIDDEN CUT HERE. The camera arrives at the entrance of a lit doorway, where, against the logics of time and space, the same woman, Maria, is seen; behind her and on the other side of the door we see a bricked surface background. The woman’s wet hair is covered by a shawl or bathrobe over her shoulders. The camera pans left as it brings her image into the middle of the screen in medium close-up. The sound of dripping water hitting a taut, stretched out linen sheet is heard, as is the returning sound of the night creature. The camera moves in on her, still in close-up, panning rightward as she begins to move quickly screen right, causing us to think that the camera has redirected its movement in a leftward pan. (49”)

22. A straight cut to an old woman in medium shot (Alexei’s mother) seen as an arch shaped reflected image (produced from a Mirror) with clouds, a tree to the left and fire near the bottom of the Mirror-picture (it looks like a Renaissance painting). She is nearly bareheaded with very little hair and has a shawl over her shoulders that she holds with her right hand crossed over her chest and touching her heart region. The camera seems to be moving screen left as the old woman appears to be advancing near it and the strange arched shape Mirror image vanishes into transparency. Only the sounds of dripping water are heard. The camera frames her in medium close-up as it moves slightly forward closer to her image, then a person (the old woman’s) right hand comes up from the bottom of the screen and rubs the surface of the image of the old woman (her image reflected in a Mirror) in a counterclockwise movement. The sound of rubbing wet glass is heard. (22”) The shot cuts. THE SHOT/SCENE BREAKDOWN ENDS HERE.

David George Menard is a Polymath Physicist and Filmmaker, a Physics MSc graduate from the University of Tennessee Space Institute, Tullahoma, TN. David went to work for Martin Marietta Missiles Systems, the Electro-Optics Division, in Orlando Florida. Unfortunately, circa 1990, the Soviet Union collapsed and many scientists lost their jobs. So he began a new career in filmmaking, attending the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema in Montreal, graduating with a MFA in film production in 2010. After which, he moved to Los Angeles and began writing screenplays, continuing to do so while promoting “Termite Cat Productions, Ltd.”

Notes

- The Stalin regime was brutal and deadly, limiting personal and social liberties, and carrying out rampant political persecution; even art and culture were subjugated to the aesthetic control of social realism, servicing the Soviet ideology. The state film industry was sponsored and financed by government subsidies, focusing on propaganda films and national epics. The Soviet cinema was based on old fashioned production systems, with a few internationally acclaimed directors (the others remained in obscurity), and suffered from the lack of good screenwriters since many Russian writers looked down to script writing as an inferior activity. All Soviet film aesthetics were centered on the concept of ‘social realism,’ a representation of national identity through national epics and heroes. The post-Stalin period began with the death of Stalin in 1953. It was a time when Soviet politics progressively opened up to the United States and split with the Chinese communist ideology. Its cinema was also characterized by a progressive opening to smaller, independent production companies, generating small scale films.The first stage of relaxation in the arts is referred to as the Khrushchev period {1958 – 1964} (Nikita Khrushchev [1894 – 1971]). It is marked by the denunciation of the excesses of Stalinism and the abolishment of the cult of personality (Stalin). The second stage occurs between 1964 and 1982 when Leonid Brezhnev [1906 – 1982] becomes the general secretary of the communist party, and a more conservative, party-centered government is set up as the hallmark of this regime. In 1957, the Union of Filmmakers is formed to protect filmmakers but it also becomes a form of control on the Soviet filmmakers because censorship is still in effect and applied to all the Soviet film industry, especially when Brezhnev is the general secretary. Experimental or art films are controlled and released only in limited circuits determined by the state. In the Spring of 1968, the USSR invades Czechoslovakia and Prague falls under the control of the Soviet Union; and at the same time, a dissident movement begins in the USSR and the deportations of dissident trouble makers becomes policy. From 1986 to 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev takes power in the Soviet Union, marking the beginning of the final stages of the Soviet government. He opens up his country to the European economy and culture by introducing the Perestroika and Glasnost politics, effectively ending state control politics over Soviet industry and economy. It also marks the end of the state controlled film industry, and the withdrawal of government subsidies provokes a crisis in the Soviet cinema because of the lack of national circuits for the production and distribution of film; as a result, censorship is terminated with an order for the re-release of films banned during the previous years. Thus, distribution of Hollywood films in the national film market is allowed and international co-productions are initiated, especially with Europe. Therefore, Soviet cinema remained in the State’s repressive grip until the advent of glasnost in 1985-86, and social realism was not categorically rejected as the official style of Soviet film art until a unanimous vote by the membership of the Filmmakers Union in June 1990.

After a military coup in 1991 (marking the end of the Soviet Union), Boris Yeltsin governs Russia until 2000. During his time in office, the Russian economy is in a continuous state of crisis. Moreover, many anti-Russian political movements spring up within former Soviet states which, seek their own independence (for instance, the war for independence in Chechnya). In 2000, Alexandrei Putin, former head of the KGB (Soviet CIA), becomes Prime minister of Russia. He sets up a conservative government but still remains open to the benefits of the Western economy, allowing collateral political cooperation. ↩

- Eisenstein believed the film image to be a composite of different shot arrangements in a structure in which collision and conflict were made to exist between its elements. Montage was at the heart of such a structure. Montage can be further divided into five categories: a) metric – tempo of the cutting based on temporal length b) rhythmic – specialized metric montage in which the cutting rate is based upon the rhythm of movement within the shot as well as predetermined metrical demands, c) tonal – dominant emotional tone becomes the basis for editing, d) overtonal – a synthesis of metric, rhythmic and tonal which emerges in the projection rather than in the editing process and e) intellectual or ideological – previous montage techniques were concerned with inducing emotional and/or physiological reactions through a sophisticated form of behavior, but intellectual montage was believed to express abstract ideas by creating conceptual relationships among the shots of opposing visual content. Furthermore since Eisenstein began his career in the Soviet theater where spectacle and attraction were a dominant part of the show, Soviet montage techniques are based on the montage of attractions, and its rhythm is developed as a sequence of images progressing through time. Its editing process can be characterized as an intellectual and conceptual juxtaposition of images, objects and concepts capable of achieving certain emotional and intellectual effects. Soviet montage/editing is based on the interplay of concepts, where the concepts dictate the editing rhythm. Therefore, Eisensteinian editing is a montage of attraction between shots, and elements in the shots juxtapose concepts, allowing the viewer to produce intellectual connections and meaning. Thus, the montage of attraction produces an explosion of meaning that arouses the viewer, and its purpose is to suggest specific ideas and concepts; and so, the filmmaker creates a new perception of social reality. ↩

- What happened to Sergei Paradjanov [1924 -1990] during the Brezhnev years was extreme. In October 1964, Nikita Khrushchev was removed from office by a conspiracy among his deputies, and Leonid Brezhnev placed in as the secretary of the Central Committee and Alexei N. Kosygin as the chairman of the Council of Ministers. There followed a period of uncertainty and indecision for the arts that ended abruptly with the Warsaw pact occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and a renewed domestic campaign against the liberation of Soviet culture in 1969. The brief interval of the Khrushchev relaxation ended with the production of one of the most extraordinary and beautiful films ever made, Sergei Paradjanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), a mythopoetic mode of experimental cinema. Like the legends of Tristan and Isolde and Romeo and Juliet, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors offers a relatively familiar and uncomplicated tale of undying love that has variants in cultures all over the world; with this film Paradjanov created a vision of human experience that was considered extremely radical in its subversion of all authority. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors violates every narrative code and representational system known to cinema, and it seems intent upon deconstructing the very process of representation itself by interrogating the whole set of historically evolved assumptions about the nature of cinematic space and the relationship between spectator and the screen. Paradjanov proceeds by means of ‘perceptual dislocation’ making it impossible at any given moment to imagine a stable time-space continuum for the dramatic action. The point of these techniques is not to confuse the spectator but to prevent the kind of comfortable, familiar, and logically continuous representational space associated with traditional narrative form. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors exists most fully not in the realm of narrative but in the world of myth and the unconscious. It is a psychological film embedded deep in Freudian and Jungian imagery, making the Pavlovian tactics of Eisensteinian montage look primitive. Psychologically, in order to tell a tale that operates at the level of myth, and not of narrative, the story becomes an archetype of life itself, where youth passes from innocence to experience to solitude and death in a recurring, eternal cycle. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors represents a set of collective archetypes, and forms a unified archetypal pattern that is composed of the ‘shadow’ (Jung’s shadow archetype) of ‘forgotten ancestors’ (Jung’s archetypes of the wise old man, trickster, Madonna), transcending individual identity (Jung’s persona archetype) and merging into the collective life force (Jung’s collective self archetype). ↩

- Tarkovsky graduated with honors in 1960, winning first prize at the New York film festival for his diploma project entitled Steamroller and Violin (1960). His first feature film was Ivan’s Childhood (1962, aka “My Name Is Ivan”), winning the Golden Lion award at the 1962 Venice film festival. Ivan’s Childhood is a story of a young war orphan boy who becomes a frontline spy for the Soviet army during WWII. Rather than following the traditional pattern of the brave and strong Socialist Realist hero, Ivan is a vulnerable, frail boy in hero’s garb. In form, this film approaches the avant-garde in its surreal rendition of the horrors of war. Tarkovsky’s next film was Andrei Rublev (1966-1971), written as a script by Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovski, which produced an official scandal. The title character is a historical figure, the Russian Orthodox monk who brought the art of religious icon painting to its zenith in the 15th century. He used Rublev’s life, reconstructed in loosely connected episodes, to symbolize the conflict between Russian barbarism and idealism. Tarkovsky’s third film was the metaphysical science-fiction entitled Solaris (1971), adapted from a novel by the Polish writer Stanislaw Lem. ↩

- This film was scripted by Tonino Guerra, who had previously worked with Michelangelo Antonioni and Francesco Rosi, and it portrays the memories, dreams, and waking experience of a Russian professor of architecture who has come to Italy for the first time, accompanied by a female interpreter of Botticelli-like beauty (Sandro Botticelli [1444? – 1510]). It is a mysterious and inaccessible film, sharing a Best Direction award with Robert Bresson’s L’Argent (1983) at the 1983 Cannes film festival. In 1983, Tarkovsky directed Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov for the London stage. ↩

- This film was shot by the cinematographer Sven Nykvist, and it is a visionary piece concerning a small group of people on an isolated Baltic island and the possibility of a nuclear holocaust. It was his last film, as he died of lung cancer in Paris in December 1986. ↩

- In the section from Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema entitled “Time, rhythm and editing,” Andrei Tarkovsky theorizes that ‘film image’ as being non-essentially composite. He proposes the dominant factor of the film image as being essentially rhythm. The passage of time is clarified by the characters’ behavior, the visual treatment and the sound -but these are all accompanying elements, the absence of which would not affect the existence of the filmic time-thrust. Tarkovsky writes that it is impossible to imagine any cinematic work with no temporal undercurrents winding through the shots, but one can conceive of a film with no actors, music, decor or even editing. Tarkovsky goes on to explain that no one component of a film can have any meaning by itself: “it is the film that is the work of art.” ↩

- Donato Totaro, “Time and the Film Aesthetics of Andrei Tarkovsky,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies/Revue canadienne d’études cinématographiques Volume 2 No. 1 (Spring, 1992): 23. ↩

- Montage of attraction does not allow the film to continue beyond the frame, nor permit the spectator to bring personal feelings to what is perceived. Montage cinema presents the viewer with conceptual allegories that the intellect breaks down into puzzles, riddles and symbols to decipher. For Eisenstein, the construction of the image-concept becomes the determinant of his cinema, where the filmmaker imposes his belief structure, which carries his emotional and intellectual attitudes about life and the world, onto the minds of the spectators. ↩

- Christie, Ian. “ Formalism and Neo-Formalism.” In The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Ed. John Hill and Pamela Church Gibson. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998, 62 -63. ↩

- His concept of the “time-thrust” is quite simple because the editor/director does not have to create the mystical effect produced by the time-images. The time-pressure intensities are inherent to the shots and exist naturally as variant forms of the rhythmic manifestations of the direct perception of time. ↩

- Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989, 40 – 41. ↩