“There are forces making for happiness, and forces making for misery. We do not know which will prevail, but to act wisely we must be aware of both.”

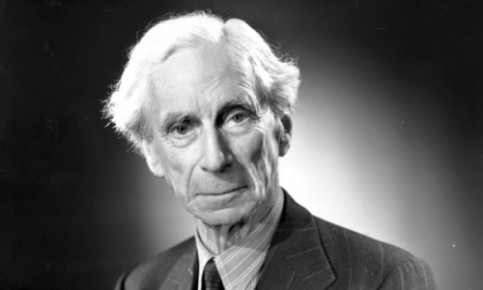

Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872–February 2, 1970) is one of humanity’s most grounding yet elevating thinkers, his writing at once lucid and luminous. There is something almost prophetic in the way he bridges timelessness and timeliness in contemplating ideas urgently relevant to modern life a century earlier — from how boredom makes happiness possible to why science is the key to democracy. But nowhere does his genius shine more brilliantly than in What I Believe (public library).

Published in 1925, the book is a kind of catalog of hopes — a counterpoint to Russell’s Icarus, a catalog of fears released the previous year — exploring our place in the universe and our “possibilities in the way of achieving the good life.”

Russell writes in the preface:

In human affairs, we can see that there are forces making for happiness, and forces making for misery. We do not know which will prevail, but to act wisely we must be aware of both.

One of Russell’s most central points deals with our civilizational allergy to uncertainty, which we try to alleviate in ways that don’t serve the human spirit. Nearly a century before astrophysicist Marcelo Gleiser’s magnificent manifesto for mystery in the age of knowledge — and many decades before “wireless” came to mean what it means today, making the metaphor all the more prescient and apt — Russell writes:

It is difficult to imagine anything less interesting or more different from the passionate delights of incomplete discovery. It is like climbing a high mountain and finding nothing at the top except a restaurant where they sell ginger beer, surrounded by fog but equipped with wireless.

Long before modern neuroscience even existed, let alone knew what it now knows about why we have the thoughts we do — the subject of an excellent recent episode of the NPR’s Invisibilia — Russell points to the physical origins of what we often perceive as metaphysical reality:

What we call our “thoughts” seem to depend upon the organization of tracks in the brain in the same sort of way in which journeys depend upon roads and railways. The energy used in thinking seems to have a chemical origin; for instance, a deficiency of iodine will turn a clever man into an idiot. Mental phenomena seem to be bound up with material structure.

Nowhere, Russell argues, do our thought-fictions stand in starker contrast with physical reality than in religious mythology — and particularly in our longing for immortality which, despite a universe whose very nature contradicts the possibility, all major religions address with some version of a promise for eternal life. With his characteristic combination of cool lucidity and warm compassion for the human experience, Russell writes:

God and immortality … find no support in science… No doubt people will continue to entertain these beliefs, because they are pleasant, just as it is pleasant to think ourselves virtuous and our enemies wicked. But for my part I cannot see any ground for either.

And yet, noting that the existence or nonexistence of a god cannot be proven for it lies “outside the region of even probable knowledge,” he considers the special case of personal immortality, which “stands on a somewhat different footing” and in which “evidence either way is possible”:

Persons are part of the everyday world with which science is concerned, and the conditions which determine their existence are discoverable. A drop of water is not immortal; it can be resolved into oxygen and hydrogen. If, therefore, a drop of water were to maintain that it had a quality of aqueousness which would survive its dissolution we should be inclined to be skeptical. In like manner we know that the brain is not immortal, and that the organized energy of a living body becomes, as it were, demobilized at death, and therefore not available for collective action. All the evidence goes to show that what we regard as our mental life is bound up with brain structure and organized bodily energy. Therefore it is rational to suppose that mental life ceases when bodily life ceases. The argument is only one of probability, but it is as strong as those upon which most scientific conclusions are based.

But evidence, Russell points out, has little bearing on what we actually believe. (In the decades since, pioneering psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman has demonstrated that the confidence we have in our beliefs is no measure of their accuracy.) Noting that we simply desire to believe in immortality, Russell writes:

Believers in immortality will object to physiological arguments [against personal immortality] on the ground that soul and body are totally disparate, and that the soul is something quite other than its empirical manifestations through our bodily organs. I believe this to be a metaphysical superstition. Mind and matter alike are for certain purposes convenient terms, but are not ultimate realities. Electrons and protons, like the soul, are logical fictions; each is really a history, a series of events, not a single persistent entity. In the case of the soul, this is obvious from the facts of growth. Whoever considers conception, gestation, and infancy cannot seriously believe that the soul in any indivisible something, perfect and complete throughout this process. It is evident that it grows like the body, and that it derives both from the spermatozoon and from the ovum, so that it cannot be indivisible.

Long before the term “reductionism” would come to dismiss material answers to spiritual questions, Russell offers an elegant disclaimer:

This is not materialism: it is merely the recognition that everything interesting is a matter of organization, not of primal substance.

Our obsession with immortality, Russell contends, is rooted in our fear of death — a fear that, as Alan Watts has eloquently argued, is rather misplaced if we are to truly accept our participation in the cosmos. Russell writes:

Fear is the basis of religious dogma, as of so much else in human life. Fear of human beings, individually or collectively, dominates much of our social life, but it is fear of nature that gives rise to religion. The antithesis of mind and matter is … more or less illusory; but there is another antithesis which is more important — that, namely, between things that can be affected by our desires and things that cannot be so affected. The line between the two is neither sharp nor immutable — as science advances, more and more things are brought under human control. Nevertheless there remain things definitely on the other side. Among these are all the large facts of our world, the sort of facts that are dealt with by astronomy. It is only facts on or near the surface of the earth that we can, to some extent, mould to suit our desires. And even on the surface of the earth our powers are very limited. Above all, we cannot prevent death, although we can often delay it.

Religion is an attempt to overcome this antithesis. If the world is controlled by God, and God can be moved by prayer, we acquire a share in omnipotence… Belief in God … serves to humanize the world of nature, and to make men feel that physical forces are really their allies. In like manner immortality removes the terror from death. People who believe that when they die they will inherit eternal bliss may be expected to view death without horror, though, fortunately for medical men, this does not invariably happen. It does, however, soothe men’s fears somewhat even when it cannot allay them wholly.

In a sentiment of chilling prescience in the context of recent religiously-motivated atrocities, Russell adds:

Religion, since it has its source in terror, has dignified certain kinds of fear, and made people think them not disgraceful. In this it has done mankind a great disservice: all fear is bad.

Science, Russell suggests, offers the antidote to such terror — even if its findings are at first frightening as they challenge our existing beliefs, the way Galileo did. He captures this necessary discomfort beautifully:

Even if the open windows of science at first make us shiver after the cosy indoor warmth of traditional humanizing myths, in the end the fresh air brings vigor, and the great spaces have a splendor of their own.

But Russell’s most enduring point has to do with our beliefs about the nature of the universe in relation to us. More than eight decades before legendary graphic designer Milton Glaser’s exquisite proclamation — “If you perceive the universe as being a universe of abundance, then it will be. If you think of the universe as one of scarcity, then it will be.” — Russell writes:

Optimism and pessimism, as cosmic philosophies, show the same naïve humanism; the great world, so far as we know it from the philosophy of nature, is neither good nor bad, and is not concerned to make us happy or unhappy. All such philosophies spring from self-importance, and are best corrected by a little astronomy.

He admonishes against confusing “the philosophy of nature,” in which such neutrality is necessary, with “the philosophy of value,” which beckons us to create meaning by conferring human values upon the world:

Nature is only a part of what we can imagine; everything, real or imagined, can be appraised by us, and there is no outside standard to show that our valuation is wrong. We are ourselves the ultimate and irrefutable arbiters of value, and in the world of value Nature is only a part. Thus in this world we are greater than Nature. In the world of values, Nature in itself is neutral, neither good nor bad, deserving of neither admiration nor censure. It is we who create value and our desires which confer value… It is for us to determine the good life, not for Nature — not even for Nature personified as God.

Russell’s definition of that “good life” remains the simplest and most heartening one I’ve ever encountered:

The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.

Knowledge and love are both indefinitely extensible; therefore, however good a life may be, a better life can be imagined. Neither love without knowledge, nor knowledge without love can produce a good life.

What I Believe is a remarkably prescient and rewarding read in its entirety — Russell goes on to explore the nature of the good life, what salvation means in a secular sense for the individual and for society, the relationship between science and happiness, and more. Complement it with Russell on human nature, the necessary capacity for“fruitful monotony,” and his ten commandments of teaching and learning, then revisit Alan Lightman on why we long for immortality.

Maria Popova

You must be logged in to post a comment Login