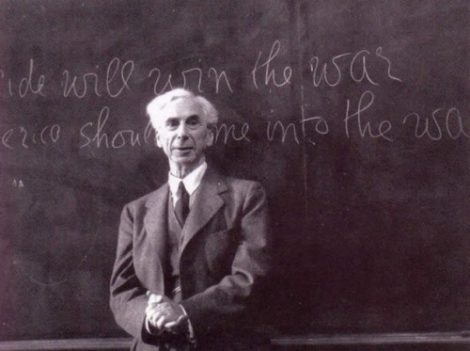

Bertrand Russell saw the history of civilization as being shaped by an unfortunate oscillation between two opposing evils: tyranny and anarchy, each of which contain the seed of the other. The best course for steering clear of either one, Russell maintained, is liberalism.

“The doctrine of liberalism is an attempt to escape from this endless oscillation,” writes Russell in A History of Western Philosophy. “The essence of liberalism is an attempt to secure a social order not based on irrational dogma [a feature of tyranny], and insuring stability [which anarchy undermines] without involving more restraints than are necessary for the preservation of the community.”

In 1951 Russell published an article in The New York Times Magazine, “The Best Answer to Fanaticism–Liberalism,” with the subtitle: “Its calm search for truth, viewed as dangerous in many places, remains the hope of humanity.” In the article, Russell writes that “Liberalism is not so much a creed as a disposition. It is, indeed, opposed to creeds.” He continues:

But the liberal attitude does not say that you should oppose authority. It says only that you should be free to oppose authority, which is quite a different thing. The essence of the liberal outlook in the intellectual sphere is a belief that unbiased discussion is a useful thing and that men should be free to question anything if they can support their questioning by solid arguments. The opposite view, which is maintained by those who cannot be called liberals, is that the truth is already known, and that to question it is necessarily subversive.

Russell criticizes the radical who would advocate change at any cost. Echoing the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke, who had a profound influence on the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Russell writes:

The teacher who urges doctrines subversive to existing authority does not, if he is a liberal, advocate the establishment of a new authority even more tyrannical than the old. He advocates certain limits to the exercise of authority, and he wishes these limits to be observed not only when the authority would support a creed with which he disagrees but also when it would support one with which he is in complete agreement. I am, for my part, a believer in democracy, but I do not like a regime which makes belief in democracy compulsory.

Russell concludes the New York Times piece by offering a “new decalogue” with advice on how to live one’s life in the spirit of liberalism. “The Ten Commandments that, as a teacher, I should wish to promulgate, might be set forth as follows,” he says:

1: Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.

2: Do not think it worthwhile to produce belief by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light.

3: Never try to discourage thinking, for you are sure to succeed.

4: When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavor to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory.

5: Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found.

6: Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you.

7: Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

8: Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent than in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter.

9: Be scrupulously truthful, even when truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it.

10. Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool’s paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness.

Source:

Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy

You must be logged in to post a comment Login