There is a Francis Bacon pope in Tate Liverpool that is barely a squeak from high camp. It shows the pontiff in sumptuous purple robes, raising his dainty little hands in a fit of girlish horror. It is a very strange addition to the long sequence of screaming popes; indeed this pontiff is not screaming so much as wincing with his eyes closed. But it makes the point, as Bacon’s paintings so often do, that there is sometimes very little distance between hilarity and nervous hysteria.

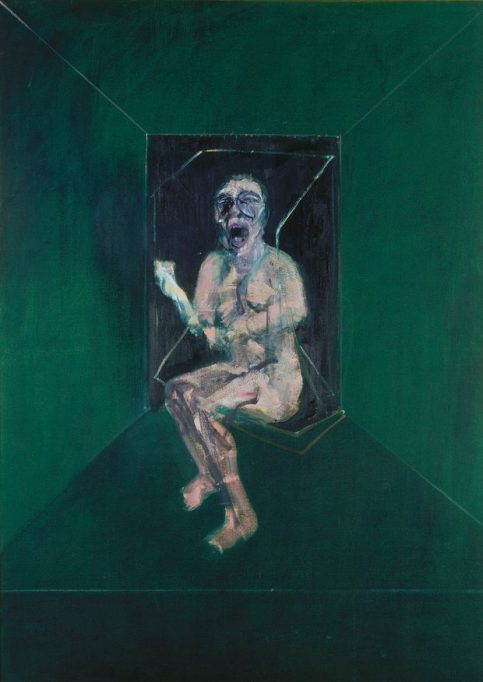

This is not why the image is currently on display in the largest Bacon show ever held in northern England. No, it is here because the figure is immured in a diagrammatic version of the throne in Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X, from which all of Bacon’s many variations issue. And more than that, he is boxed in a black cube (within an already dark painting) that might be the very definition of an invisible room.

This phrase, which gives the show its subtitle, was coined by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze in a famous meditation on Bacon. Deleuze was preoccupied by the painter’s strange and original pictorial space. This is so familiar by now that it is odd to come across a Bacon that doesn’t have that flat backdrop of glowering darkness or gorgeously rich colour; that doesn’t have those architectural sketch-lines hinting at cubes, cages, arenas, plinths or cells; that doesn’t have those thin black or white lines, sometimes scumbled, sometimes spectral, sometimes incisively clear.

Often they set a scene quite precisely: a window and the door of a hotel room; a parlour with curving architecture and a portrait by Bacon hanging on the wall; a sheaf of vertical lines that look like the shimmering strip curtains of an otherwise sepulchrally dark nightclub, though this might also be the anteroom of hell, given the contortions of the figure.

This man is Peter Lacey, one of Bacon’s lovers, who appears in another painting apparently mired to the waist in a newscaster’s kidney-shaped desk, except that this is 1957 and they hadn’t yet been invented. Nor indeed had Samuel Beckett yet written of Winnie, up to her waist in sand in Happy Days. For all that Bacon found so many of his sources in the past – Velázquez, Eadweard Muybridge’s motion photographs, Victorian boxing, Picasso’s cubist distortions – his visions often leapt in advance of western culture.

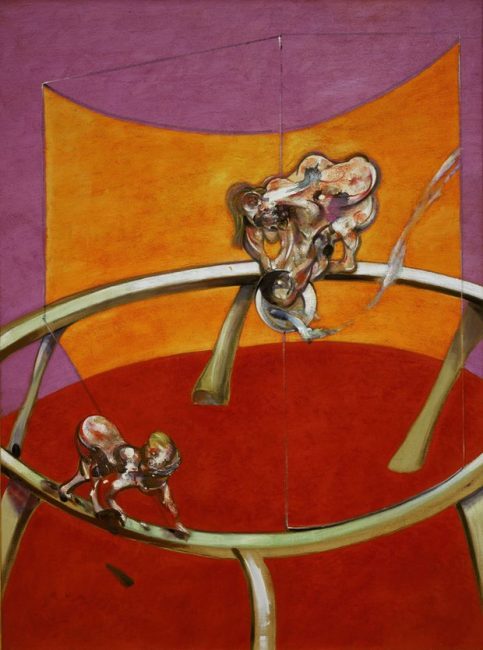

Since these diagrammatic structures appear everywhere it seems an odd theme for a show: practically anything by Bacon might be admitted, for one thing, and attention to these schematic stagings, what’s more, seems quite unnecessary. The relationship between ground and figure, to use that old phrase, has always felt conspicuously theatrical in Bacon’s work. His pictures are stage sets with wings, entrances, scenery and downstage performances in which the figures stand out starkly against the backdrop, sometimes in ellipses like spotlights.

And while the curators harp on about the usual themes of postwar futility, theatrical alienation and existential angst, it is worth pointing out that when the art critic David Sylvester asked Bacon about those invisible rooms, he simply replied: “I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles which concentrate the image down.” They are there to highlight, to focus, to point to the figure. They are intensifiers.

Tate Liverpool has managed to borrow 29 major works from European collections, such as the outstandingly sinister painting of a child creeping round a circuit on all fours from Amsterdam, and the raw, screaming figure of the nurse in Battleship Potemkin, trapped in some kind of cage-like swing, from the Städel Museum in Frankfurt. In each case the mise-en-scène implies a horrifying perpetuum mobile.

It gets worse in the Hirshhorn Museum’s immense Triptych, where the bodies appear thrashed to a pulp and contained in some kind of glass case raised up on a platform. An observer, hanging on the phone, peers at them through the glass. And in an anonymous hotel room with a deep blue view some terrible bloodbath has apparently occurred: or are these simply bloodstained clothes tumbling out of a case? It is hard to know what is going on in this sequence – as hard as Bacon wanted it to be.

For what is really going on in his opera of gaping mouths and writhing figures, what is Bacon actually doing with – to – his figures? Flanged, spraddled, twisted, split apart and reassembled like the botched and shattered faces in Henry Tonks’s first world war portraits, they appear to twist and melt, materialise and evaporate against the backdrop in nameless torsions. How this is done remains elusive. Bacon used the grainy back of the canvas, and somehow got his paint to seep into the surface like blood – very often while describing blood with exceptional brilliance, and his drawings (many shown here) indicate all sorts of sources, from medical textbooks to monkey manuals. But still these morphings remain defiantly mysterious.

And they veer quite melodramatically from violence to Carry On comedy. A mouth yowling in silence becomes funny when the teeth inside are awfully clean and tidy. A brutal coupling, when the bodies are as hard to tell apart as eels in a pail, gets a comic punchline with a neatly painted packet of fags. John Berger long ago compared Bacon to Walt Disney, and this goes to the balletic exuberance and graphic zip of his art. All these rectangles, cubes and ellipses are marvellously concise and strong. Whatever else, they keep the wild dynamism in place.

Whether they describe actual places, too, will perhaps become clearer when Martin Harrison’s immense Catalogue Raisonné is published next month, with its revelation of many unfamiliar paintings. In the meantime, their ingenious ambiguity is apparent all through this show. Here is the ghoulish circus ring that doubles as a cattle pen; here is the black void that might be an electric chair. Narratives begin to form in your head – is this figure trapped in a gas chamber, or a witness box; is this ectoplasm gas or a man’s shadow? – but the story is sidelined every time by the sheer force of the image. The lesson of Liverpool is that Bacon’s art is exactly what he wanted it to be, no matter how many ways we might like to explain it: not stories but pictures that hold their own, a set of deathless, inexplicable images.

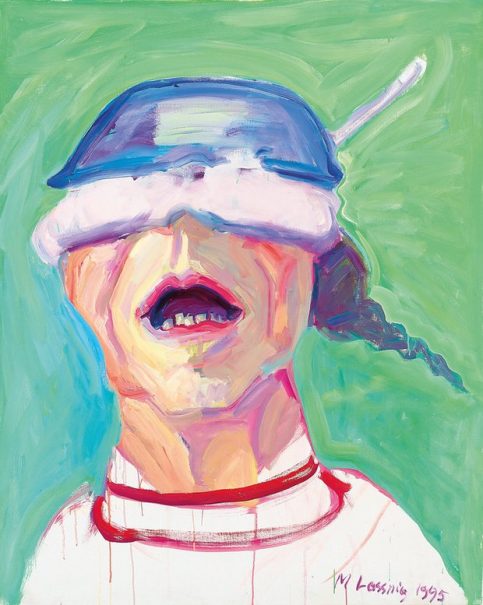

In an embarrassment of riches, Tate Liverpool is also presenting a show by the late and very great Austrian painter Maria Lassnig (1919-2014), which appears to have strong links with Bacon. Lassnig was also compelled by the experience of having, and being, a body; with sex and death and mordant humour. Her coinages are superb, especially with the self-portraits: herself as a shrieking cheese grater or a saucepan head, herself as triangle jabbing away at a square. She clambers out of the canvas, sinks into it, emerges from it like a newborn baby. Painter and painting are inseparable.

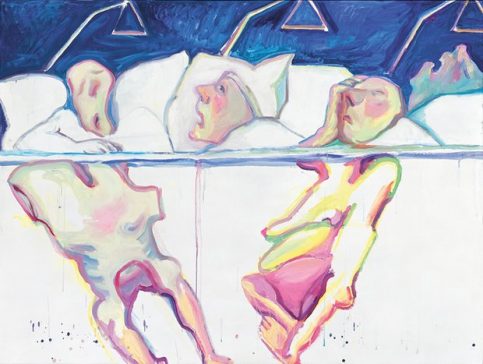

The late works, which seem to grow brighter as she aged, are masterpieces of courageous invention: above all, paintings such as What Next?, where the woman is becoming a thing of paper, and Hospital, which shows what few artists have ever portrayed. Three heads lie on pillows beneath triangular lights. They are dozing, suffering, waking; but beneath the sheets, like a tideline, their poor thin bodies are dying away. It is a most magnificent picturing of mortal illness and it has a quality that Francis Bacon lacks: the abiding power to move the viewer.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login