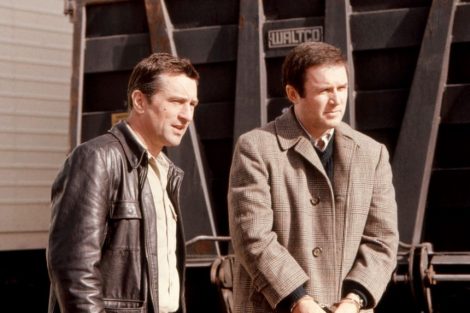

How the combo of Robert De Niro going comedic and Charles Grodin getting neurotic turned an action-comedy into an endlessly rewatchable classic.

“Jack, you’re a grown man. You have control over your own words.”

“You’re goddamn right I do. So here come two words for you: shut the fuck up.”

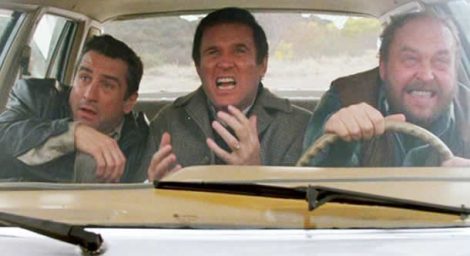

Over the course of Midnight Run, bounty hunter Jack Walsh (Robert De Niro) and fugitive accountant Jonathan “Duke” Mardukas (Charles Grodin) travel over 3000 miles as they crisscross America by virtually every mode of transportation possible: commercial jet and biplane, passenger train and cargo train, three stolen cars and a borrowed station wagon, even a brief swim through rapid waters. They are being pursued at all times by a cadre of FBI agents, a kingpin’s henchmen and a rival bounty hunter. They get involved in three car chases and multiple gunfights; Jack shoots a helicopter out of the sky with a pistol. The film clocks in at two hours and seven minutes (an eternity by the action comedy standards of the time), features half the character actors worth their salt circa 1988 and includes extended riffs on a variety of food stuffs: chorizo and eggs, Lyonnaise potatoes, cream soda and fried chicken. Like Jack’s promised two-word insult to the Duke, it runs to excess. Yet all that ultimately matters – and makes the movie a classic worth revisiting on the 30th anniversary of its release – are two other words: Walsh and Duke.

Or, if you prefer, De Niro and Grodin.

The 1980s were a glorious period for buddy movies featuring abundant mayhem: 48 Hrs, Lethal Weapon, The Blues Brothers, Running Scared and Planes, Trains and Automobiles, to name just a few of the best buddy films ever. But there’s something special about the bond between Jack and the Duke, and the onscreen chemistry between the two stars, that elevates their pairing even above their contemporaries.

It’s a team-up that nearly didn’t happen. The movie gives disgraced ex-cop Jack has five days to bring the Duke from New York to LA to collect a big reward that will allow him to open up a coffee shop, while the Mob accountant tries to avoid being murdered in prison by drug dealer Jimmy Serrano (Dennis Farina, in the best performance of his career), from whom he stole $15 million to give to charity. De Niro, who had been looking to do a comedy after a 15-year run as Hollywood’s most intense method actor, only took the role as a consolation prize when he lost out to Tom Hanks for the lead in Big. Paramount was originally set to make it as director Martin Brest’s big follow-up to Beverly Hills Cop. But the studio wanted to tweak George Gallo’s script to make the Duke a woman (the Duchess?) played by Cher, hoping to generate some sexual tension. Brest said no to that, and to having Robin Williams play the part, because he’d been so dazzled by Grodin’s audition opposite De Niro. At that point, Paramount abandoned the project altogether and it wound up at Universal, whose executives approved the unconventional casting.

Grodin wasn’t a box office draw, and he was famously difficult to work with – I once attended a screening of the film that was followed by a Q&A with Grodin, who (when he wasn’t trying to change the subject to the advocacy work he does on behalf of non-violent criminal offenders) told multiple stories of on-set feuds, all of them painting him as the victim. Whatever spark Brest saw in that audition, however, was there on the screen. De Niro and Grodin’s energies are perfectly mismatched throughout the film: the former tweaking his famous alpha-male persona just enough to get laughs while still seeming like a genuine threat to punch his co-star into next week; the latter neurotic and deadpan, turning his fundamentally annoying nature into a weapon. And the Duke is as much a tough guy as Jack, just in a very different way – it’s why they manage to get one over on each other frequently, rather than the competition being unfair because Jack has a gun and handcuffs.

It had become something of a De Niro trademark in movies like Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Untouchables to repeat dialogue over and over; here, Grodin turns that against him, as the Duke repeatedly badgers Jack with the same lines (“Why are you unpopular with the Chicago Police Department?”) to get under his skin, and hopefully distract him long enough to make escape. We’re on Jack’s side at the start, but there’s something admirable and even endearing about how easily his traveling companion learns to push his buttons. He turns this simple-seeming job – the “midnight run” promised by the title – into the road trip from Hell, thanks to the combined efforts of the Duke, Serrano, fellow skip tracer Marvin Dorfler (John Ashton) and exasperated FBI man Alonzo Mosely (Yaphet Kotto at his liveliest).

Grodin didn’t have the acclaim for his improvisatory skills the way that Robin Williams did, but Brest understood that the relationship between the two men would best be cemented through improv, and he gave Grodin frequent license to deviate from Gallo’s script. This is done to greatest comic effect when the Duke borrows the FBI badge Jack stole from Mosely to scam a grocery money out of a couple of gullible bartenders (“Are you doing the litmus configuration?”), but its most important use in the film comes a few scenes later, when the two men are riding the rails hobo-style:

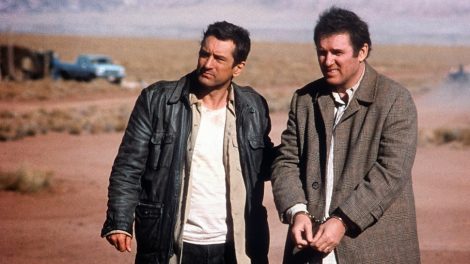

Brest’s direction to Grodin at the top of the scene was very simple: do whatever is necessary to make De Niro laugh. And while it’s Grodin who ultimately unleashes the loudest laugh of the scene after the line about how they’d still hate each other under other circumstances, the “good-looking chickens” riff does loosen up his costar enough to make the emotional transition after possible. By this point, the men have been through an awful lot together, including several near-death experiences and a painful family reunion (we’ll get back to that), so it’s possible their brief moment of mutual vulnerability and kindness would feel earned even without the farm-animal jokes. But like so much of a movie that’s overstuffed on paper but never feels that way when you watch it, that added flourish is everything: Jack really might enjoy the Duke’s company in another life.

At a time when few believed he could be the star of a mainstream comedy, De Niro is completely comfortable in both the skin of Jack Walsh and the jokey tone of the movie. Even before his character finds the Duke, the actor is clearly having a blast playing a downtrodden wiseass with no fucks left to give, whether he’s busting the chops of bail bondsman Eddie Moscone (Joe Pantoliano) or deflecting Mosely’s queries about the Duke by asking the FBI agents about their sunglasses. (“Are they government issue, or do all you guys go, like, to the same store to get ’em?”) It’s particularly striking, and disappointing, to compare his work here to the more overt self-parody he started doing circa Analyze This and Meet the Parents. In those movies, De Niro is putting in minimal effort, assuming his mere presence is enough to sell the jokes. Here, Jack feels fully lived-in, which makes the punchlines feel richer, grounds some of the more ridiculous action set pieces (see: the helicopter chase) and makes the story feel just real enough for its outcome to matter as something more than a screenwriting exercise. If the star were coasting, the scene where a mortified Jack goes to visit his ex-wife Gail (Wendy Phillips) to borrow money wouldn’t feel quite so sad, particularly when their argument’s interrupted by the arrival of Denise (Danielle DuClos), the daughter Jack had to abandon when he wouldn’t go on Serrano’s payroll.

That scene – particularly the moment when Jack, at a loss for what to say to his not-so-little girl after all this time, asks “Are you in the eighth grade?” – is startlingly honest and raw for a movie like this. Yet it informs everything we’ve already seen and everything that’s to come. It makes us understand just how much Serrano cost him, how badly he needs redemption (even if it comes in the form of a coffee shop that would, according to the Duke, be a very bad investment) and, once Serrano’s henchmen get their hands on the Duke, how much we want to see both men get a victory over this gangster. (Even a detail so small as Jack making sure the Duke’s coat doesn’t get caught in the car door as they quietly leave Gail’s house speaks volumes about how much their relationship changes in the aftermath of this painful encounter.) And we have to believe the decision the bounty hunter makes about his ward at the movie’s end at least as much as we have to root for it.

All buddy movies are a delicate balancing act, particularly since so many of them involve “buddies” who plausibly hate each other’s guts for at least half the film. With so many action sequences, so many different forces working against Jack and so many shifts in tone from silly (the argument about who lied to who first) to deadly serious (Serrano calmly telling the Duke what he plans to do to him and his wife), the balance for Midnight Run was more delicate than most. Even when you factor in all those endlessly quotable lines (“Is this Moron Number One? Put Moron Number Two on the phone”), the murderer’s row of That Guys playing cops and hoods, Danny Elfman’s bluesy score and all the other things the movie has working in its favor, it could have all fallen apart if De Niro and Grodin didn’t click as spectacularly as they do.

Every now and then, there’s talk of a sequel. I get it. The movie was a modest hit in 1988 (and the first real commercial success for De Niro as a leading man), but it was a cable staple for years. Many screenwriters and showrunners who grew up on the film cite it as an influence. But leaving aside the usual problems associated with long-delayed sequels and the passage of time – a septuagenarian Jack who jumps into a raging river is scarier in a much different way than when the middle-aged version did it – there’s the fact that every iteration has involved the character coming out of retirement to help the Duke’s son, because (among other reasons) Grodin won’t work outside the NY/NJ/CT area anymore. If he’s not part of another Midnight Run (not to be confused with Another Midnight Run, the first of three forgettable TV-movies starring Christopher McDonald as Jack), or just has a glorified cameo, what’s the point? Then it becomes another case of De Niro cashing in on a beloved role from earlier in his career, without the two combined words that made the old film so magical.

The Duke’s taunt of “See ya in the next life, Jack!” as he thinks he’s escaped his captor by train becomes first a running gag, then the movie’s emotional touchstone, as well as the last words these two unlikely allies say to each other. It’s nice to imagine them coming back together in the next life. But the journey they undertook in this one can’t be improved upon.

‘Midnight Run’ at 30: In Praise of the ‘Casablanca’ of Buddy Comedies

You must be logged in to post a comment Login