Two centuries before Einstein, Hume recognised that universal time, independent of an observer’s viewpoint, doesn’t exist

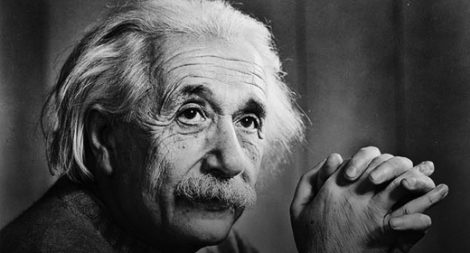

In 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to the philosopher and physicist Moritz Schlick, who had recently composed an article on the theory of relativity. Einstein praised it:

‘From the philosophical perspective, nothing nearly as clear seems to have been written on the topic.’ Then he went on to express his intellectual debt to ‘Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.’

More than 30 years later, his opinion hadn’t changed, as he recounted in a letter to his friend, the engineer Michele Besso: ‘In so far as I can be aware, the immediate influence of D Hume on me was greater. I read him with Konrad Habicht and Solovine in Bern.’ We know that Einstein studied Hume’s Treatise (1738-40) in a reading circle with the mathematician Conrad Habicht and the philosophy student Maurice Solovine around 1902-03. This was in the process of devising the special theory of relativity, which Einstein eventually published in 1905. It is not clear, however, what it was in Hume’s philosophy that Einstein found useful to his physics. We should therefore take a closer look.

In Einstein’s autobiographical writing from 1949, he expands on how Hume helped him formulate the theory of special relativity. It was necessary to reject the erroneous ‘axiom of the absolute character of time, viz, simultaneity’, since the assumption of absolute simultaneity unrecognisedly was anchored in the unconscious. Clearly to recognise this axiom and its arbitrary character really implies already the solution of the problem. The type of critical reasoning required for the discovery of this central point [the denial of absolute time, that is, the denial of absolute simultaneity] was decisively furthered, in my case, especially by the reading of David Hume’s and Ernst Mach’s philosophical writings.

In the view of John D Norton, professor of the history and philosophy of science at the University of Pittsburgh, Einstein learned an empiricist theory of concepts from Hume (and plausibly from Mach and the positivist tradition). He then implemented concept empiricism in his argument for the relativity of simultaneity. The result is that different observers will not agree whether two events are simultaneous or not. Take the openings of two windows, a living room window and a kitchen window. There is no absolute fact to the matter of whether the living room window opens before the kitchen window, or whether they open simultaneously or in reverse order. The temporal order of such events is observer-dependent; it is relative to the designated frame of reference.

Once the relativity of simultaneity was established, Einstein was able to reconcile the seemingly irreconcilable aspects of his theory, the principle of relativity and the light postulate. This conclusion required abandoning the view that there is such a thing as an unobservable time that grounds temporal order. This is the view that Einstein got from Hume.

is a visiting scholar in the department of philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is interested in the history and philosophy of science, the philosophy of David Hume, and the philosophy of time.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login