Auguste Rodin made sculpture modern by wrestling with its past. His art is a tangled sensual battle of old and new in which Michelangelo and the classical nude give birth to expressionism, surrealism and even dadaism.

A “lost” work by Rodin that has just resurfaced in Switzerland after a century exemplifies how passionately he embraced art’s noblest traditions – and how boldly he made them new.

is his only bronze cast of a violent image that grew out of his masterwork The Gates of Hell. It shows a man struggling desperately with a giant snake, his naked muscles straining as he defies its venomous attack. This terrific work has been given to the Museum of Fine Arts in Lausanne. In it, Rodin takes on rivals from the past and battles with the inner power of sculpture itself.

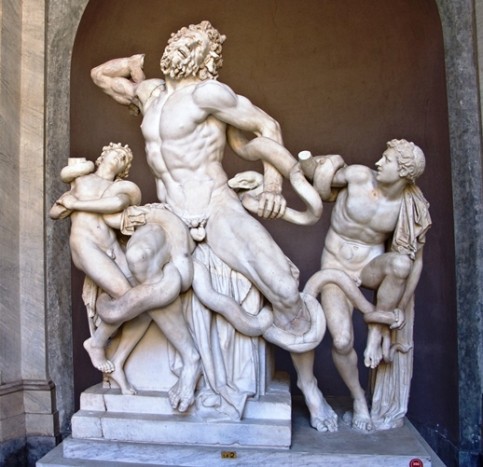

The unmistakable inspiration of this serpentine glory is the Laocoon

in the Vatican Museum, an ancient masterpiece that was dug up in Rome in 1506 and became one of the classical works Renaissance artists most admired. Laocoon and his sons are being killed by giant snakes: as he fights for their lives, Laocoon’s face is a mask of suffering. Michelangelo himself was there when it was excavated in a Roman vineyard and the contortions of Laocoon echo through his art. Just as Laocoon fights the serpent, Michelangelo’s slaves struggle with or fatally accept their bonds.

Rodin’s Man with Serpent is potently Michelangelesque, resurrecting the anguish of this most forceful of sculptors. The sensual struggle Rodin has created resembles the twisting morass of bodies in Michelangelo’s teenaged masterpiece The Battle of the Centaurs. Yet in taking on the Renaissance, Rodin changes art itself.

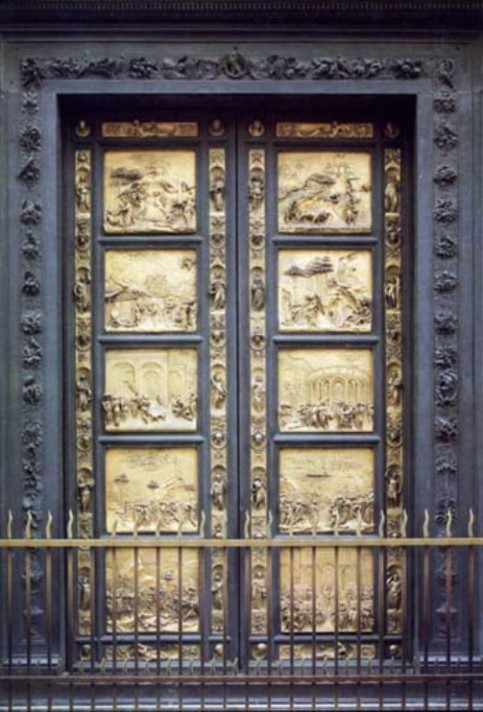

His artistic ambition was colossal. Rodin set out to match and outdo the masters. His immense project The Gates of Hell,

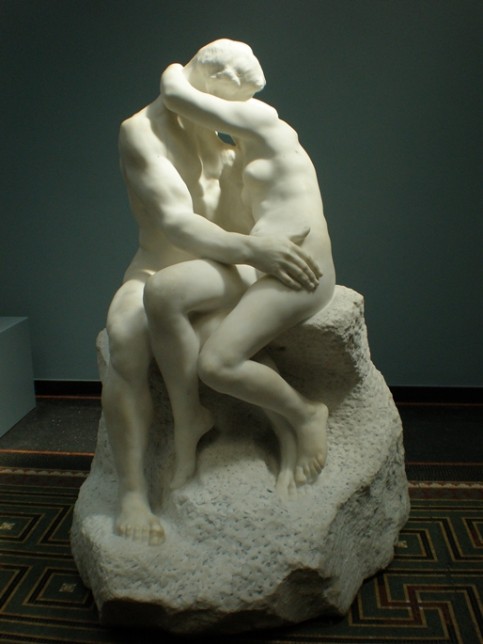

out of which this and many of his other figures (including The Kiss)

originate, was an attempt to recreate the portal to the underworld described in Dante’s Inferno. In fact, Rodin shows practically the whole of the Inferno in his recreation of Hell’s gates. At the same time he competes with the 15th-century Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, whose doors depicting the Bible are known as The Gates of Paradise.

Damn braces us, wrote William Blake. Hell is energy, and energy is eternal delight. Rodin is of the devil’s party and he knows it. His vision of hell is non-judgmental and post-Christian: this world of sex and death is, for Rodin, simply the human condition. Thus he takes the great moral struggles that tortured Michelangelo and makes them purely carnal, existential, erotic. The man fights the serpent not because of any god or curse, but because life is an orgy of desire and terror. Rodin is the first and greatest sculptor of the modern condition and this is a slithering icon of his provocative genius.

Jonathan Jones

You must be logged in to post a comment Login