Everyone has to start somewhere.

Geniuses are not born with knowledge, but come to it by their ability to absorb, retain, and apply that which they learned. We all know Kubrick was the typical ne’er-do-well who did poorly in school. His loathing for institutionalized learning was legendary. Home movies show he was affable — even attention-grabbing — but few thought he would amount to much and what aptitude he did harbor was kept well hidden except for his hobbies — chess, jazz drumming, and photography.

The gift of a camera and his aptitude in the darkroom changed him, as it does for many shy boys who suddenly find independence through their interests. Something clicked. Becoming the high school photographer brought him out of his homebound shell. Gaining access to an extraordinary world beyond the frame caused the young boy not only to blossom but also find early success and notoriety. The rest, as they say, is history.

Geniuses also tend to have a preternatural fear of being different, although many hide it very well through various means. They have great talent, think differently than everyone, and usually accompanied by larger-than-life personalities yearning to break free but often all they want is to be just like everyone else. Sometimes they find their passion.

Other times their passion finds them. I suspect for most, time and tide passes many by who have great potential to fly but are grounded by bad luck or bad choices into a life of mediocrity. Kubrick was one of the chosen few and an early opportunity was self-willed into a lasting career. “Will” is a key ingredient. Genius is earned — it is not applied for or altruistically given.

Kubrick was of Austrian, Romanian and Polish descent and first lived in the Bronx, New York. By his own admission, he never “learned anything at all in school and didn’t read a book for pleasure until [he] was 19 years old.” He was sickly and attendance at school was extremely spotty. He was home-schooled for long periods of time. He generally performed poorly in school – graduating with a D+ (or C-) average — which prevented any thought of college.

Kubrick was raised in an upper-middle class environment and showered with attention but suffered difficulty in social circles, especially in school. He was sent to California at least once as a type of coping mechanism for him and his parents, thinking the light and space would do the young man good. Even though he often described his IQ as “low,” this is clearly not the case. In reality, it was stratospheric and he was probably just bored.

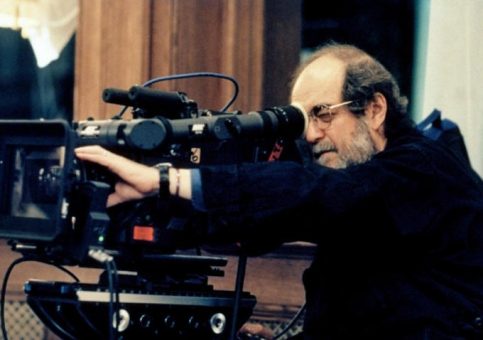

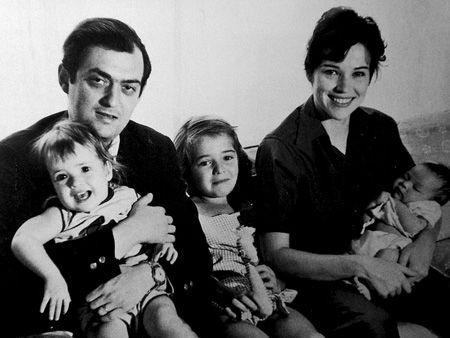

Kubrick was a modest man, mostly, and differentiated himself by wearing a black jacket and tie to the movie set. He ruled his dominion with quiet certitude. By A Clockwork Orange, scruffy overalls and an unkempt beard replaced his black jacket in the early 70s and he would rarely be seen in public again. Unless he was sleeping, which was less and less, he never stopped working on films. His workaholic nature most likely killed him in the end.

We can already see how aspects of his young life would form a basis of experience for later films. By all accounts, Kubrick was a mellow, contemplative, an emotionally distant youngster and adolescent. Most of the main characters that populated his films were similar in mood and temperament — you write about what you know, right? A keen, steady gaze and a knack for solid decision-making hewn from 1000s of hours playing chess prepared him early for life as a director. Freed from school, his intellect blossomed. He was always described as intense. He read constantly and his life became all filmmaking all the time.

All geniuses must have a cadre of other geniuses who influence their thinking and methodologies, or inspire them to veer left when going right would have been more conventional. This article is an attempt to discuss 10 of Stanley Kubrick’s most significant influencers and how they relate to his career, his work, and his personality. Interestingly, unlike most of the names in this list, Kubrick did not have a middle name.

1. Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein and 2. Vsevolod Illarionovich Pudovkin

Editing and Acting Theory

I put these two together because there is much overlap. Both were great originators, both were great directors, both developed theories of montage that became an indispensible part of the Soviet Montage Theory, both wrote books and essays that became landmark publications on film, and both have been repeatedly mentioned by name by Kubrick.

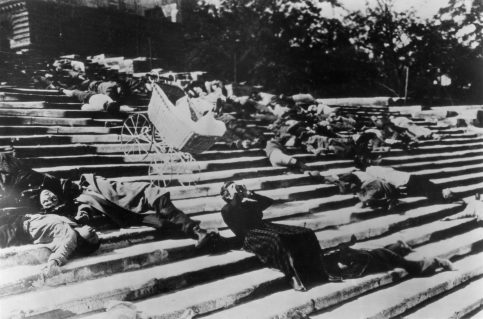

One of the first great Russian film directors was the Sergei Eisenstein. He directed several features, the most famous being the silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925), and October: Ten Days that Shook the World (1927), and later, the sound film Ivan the Terrible Part I (1944). His major writings include Film Form: Essays in Film Theory (1949) and The Film Sense (1942).

Vsevolod Pudovkin was best known for further developing theories of montage and his book, Film Technique and Film Acting (1958). It is his best-known work and has remained a seminal resource to young, budding filmmakers yearning to learn the craft.

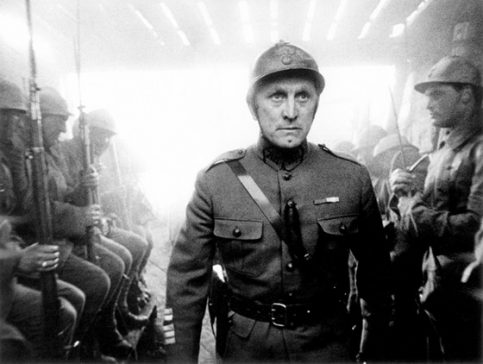

Eisenstein and Pudovkin were the masters of Soviet propaganda cinema for decades and often were in direct competition for attention and accolades. While Eisenstein used montage to bolster power to the masses in large, stupendous set-pieces, Pudovkin preferred a quieter, gentler approach that concentrated on individual courage in the face of overwhelming oppression.

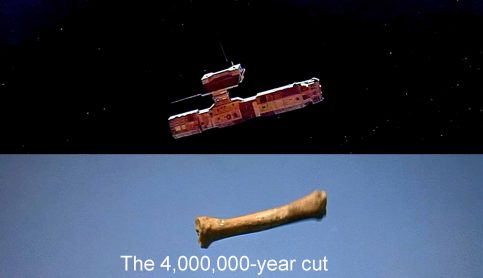

Without a doubt, there are bits and pieces of both Russian directors littered throughout Kubrick’s work. A Clockwork Orange was a complete, grand homage to Eisensteinian cinema as much as Paths of Glory was to Pudovkin. The cut from bone to spacecraft in 2001 – and a jump in time of millions of years – was pure Eisenstein. Lolita and Eyes Wide Shut were closer to Pudovkin’s individual struggle against social forces beyond their control.

That Kubrick’s films have always retained a Russian reliance on cinematic tropes, odd structures, and hard, distant characters is no accident and has often been misunderstood. Critics railed against Kubrick’s cool detachedness, his odd juxtapositions, and his infernally intellectual and obscure references. Little did anyone suspect this was not an accident but a deliberate form following function, based on theories first developed by the coolest, hardest, most detached filmmakers on the planet.

It is interesting that Kubrick would attach himself to Russian filmmakers and not to the titular father of cinema, American D. W. Griffith. Kubrick was a great admirer of Griffith’s films but that is largely where the connection ends.

Griffith humanized story and gave it warmth, artistry, subtlety, and an epic quality distinctly American. With Lillian Gish, he created a legendary film star that centered on relationships, love, despair, hope, and last-minute rescues, her blossoming womanhood a perfect foil for his brand of populism.

Where the Russians were technical, aggressively didactic and propagandistic, not to mention lacking any semblance of story, Griffith was a humanist and from his humanism and gift for dramatically expanding the language of cinema, he single-handedly created an industry 10 years before Eisenstein learned the craft.

Orson Wells said “…no town, no industry, no profession, no art form owes so much to a single man.” Kubrick’s affinity for all things European drove his professional curiosity out of country to outlier, even renegade filmmakers and philosophers. Telling a conventional story warmly was far from his mind.

3. Maximillian Oppenheimer (aka Max Ophüls)

Camera Movement

Kubrick admired a great many filmmakers but was influenced by a relative few. Aside from the Russians, he was influenced by none more so than Max Ophüls (who changed his name after immigration to America) — a Jewish, German-born filmmaker from Sarrbrücken known principally for sweeping, complicated camera movement at a time when cameras and their sound-proof housings were the size of Volkswagens and very difficult to move.

Ophüls became fascinated with camera movement as a young assistant to Anatole Litvak — a Ukrainian-born filmmaker — who, prior to Ophüls, was a great practitioner of this technique. Ophüls made 25 features, none more important than Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948), La Ronde (1950, Roundabout), La Plaisir (1952, House of Pleasure), The Earings of Madame de… (1953), and Lola Montès (1955).

Other than Unknown Woman, the rest were made after he returned to France a few years after end of the WWII. Similar to Kubrick’s experience much later, Ophüls’ Hollywood apprenticeship was not to his liking and he left it at first availability. It is unknown if the two masters ever met either in Hollywood or Europe.

Camera technique and movement isn’t the only thing Kubrick borrowed from Ophüls to provide a framework. Kubrick also used waltzes as a stylistic trend in three films in particular — Paths of Glory, 2001, and Eyes Wide Shut.

The waltz is a ritualized, formal German dance, and waltz music is primarily associated with Vienna, Austria. Despite its highbrow nature, in any dance, the closeness of the couple masks an undercurrent of sexual tension, dominance, and submissiveness done in a setting that is controlled, chaperoned, and publicly acceptable. Some liken it to a paradox. Sociologically, it’s a way for evolved societies to temper their frustrations and suppress the libidinous ways. Violent societies, after the great fall, usually become very polite ones.

For Kubrick, as they were with Ophüls, waltzes and camera movement made a kind of push-me-pull-you leitmotif that can be seen as a variety of different metaphors and meaning, depending on the situation. Kubrick, obsessed with the family unit, of manners and morals, repression and aggression, and the empty space in-between, borrowed many film techniques to visualize this inner space. Always the innovator, he took a benign technique and made it a life force.

James Mason worked on two Ophüls and one Kubrick film. He admired Ophüls enough to write this short poem. History does not show he was similarly inspired about Kubrick.

A shot that does not call for tracks

Is agony for poor old Max

Who, separated from his dolly,

Is wrapped in deepest melancholy

Once, when they took away his crane,

I thought he’d never smile again.

4. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Dogma

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was one of the most polarizing forces of nature who ever lived. Not so much for his demeanor than for his words. Firebrand, scourge, originator, cultural critic — a true Renaissance man who was extremely well-educated — he wrote poetry and was a formidable Latin and Greek scholar. He influenced many, many artists and the world alike with his deeply probing, deeply influential, deeply controversial philosophy.

Millions of words have been written him and the meaning of his works. I am not going to rehash all of it. Mainly, Nietzsche wrote about the will to power, the Übermensch (Overlord or Superman), and eternal recurrence. He was a firm believer in the now and actual, and fully embraced the realities of our present lives over what might exist in the world beyond, if anything. He was an avowed atheist and considered religion to be a man-made creation that corrupted man’s ability to free will. His impact was enormous and still felt today.

Artists gravitate to Nietzsche like white on rice. Kubrick is no exception. Composers, painters, filmmakers, photographers, and many others have all produced works based on Nietzsche’s philosophical writings. There is something strangely attractive and alluring — even forbidden — about them. They pander to weaker artist’s sensibilities to rise above the stamp of authority that prevents their ascendency, as well as support and promote a stronger-willed genius his king-of-the-world status.

One of the fundamental questions of all art is who are we, where did we come from, and what lies beyond? Nietzsche addresses all of that in a particularly nihilistic but somehow transcendent and quixotic way. His writing is astonishingly powerful, his prose enveloping, his thoughts inscrutable — but he is rarely judgmental without good reason. True enough, he does criticize organized religion most strenuously, but his reasons are clearly stated for reasons central to his concept of Will. One can take it for what it’s worth.

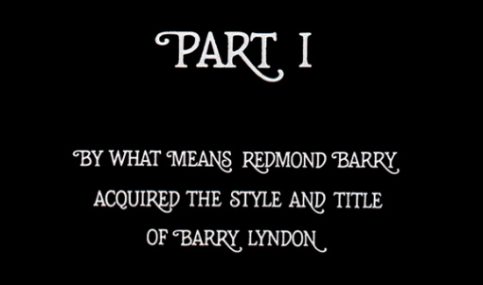

Kubrick, too, questions without moralizing. Religion as spoken dogma rarely enters into his films except for the odd scene or character. A Clockwork Orange has a Chaplain, as does Barry Lyndon. But the concept of religion as an antidote is turned on its ear: Alex “reforms” his ways after he befriends the prison Chaplain but little does the Chaplain know that Alex augments his fantasies with violent and sexual imagery from the Old Testament!

Other than standard Christian tropes, the minister says significantly little. Reverend Runt in Barry Lyndon says even less except mostly to scowl and hate on Barry. Kubrick’s anti-heroes are still allowed full reign to terrorize free from God’s judgment or from the director’s.

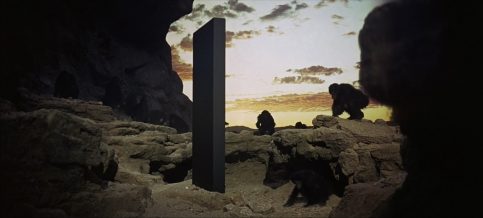

In 2001: a space odyssey, all that changes. God is at the very heart of the film — Kubrick has even said as much in interviews. This is rather odd because he is never mentioned by name and because the film is so overwhelmingly Nietzschean in the most sonic, extraordinary way. It classically, confrontationally, pits the two opposing philosophies — that are more like matter and anti-matter — on a collision course to see which one can create the most desirable type of human.

It’s a brilliant dichotomy. The monolith is clearly a sentient, intelligent being who acts as a change agent at seminal moments in the film but, beyond that, little else is explained in this largely wordless film. What is telling is Kubrick’s script was quite wordy and explained everything.

Late in the editing process he removed all of the expository dialog, voice-over narration, and any scenes that told too much and — in true Eisensteinian fashion — crafted a brand new film language much less a brand new film. Perhaps in some odd way, Kubrick emulated D. W. Griffith after all. What remained was unlike anything anyone had ever seen, even to this day.

Kubrick gives us a modern world that is desolate in spirit, cold in character, and empty in emotion. Civilization is too absorbed in its own technologies to notice or care, all the while eating itself to death in the vacuum of space. There is dialog but little is really said. There is action but little really happens. Emotions are all but non-existent. Man has become little more than a parody.

A meeting of great importance — where the main topic is how to break the news of confirmed extra-terrestrial existence to world — is handled in a way that is only slightly more complicated than ordering a hamburger. Indeed, one of the films best visual jokes is the extremely complex set of directions one has to read in order to use the toilet.

2001 reflects a great bitterness in Man’s progress of consciousness. Oft quoted, one of Nietzsche’s most famous lines is this: What is ape to man — a ridicule, a grievous shame. And that is what man is to the Superman — a ridicule, a grievous shame. The entire film becomes a riff on the Nietzschean presumption of Will.

The rebirth of Bowman into Starchild is not necessarily a thing to rejoice. First we should ask: what is there that is worth saving? What, exactly, is the Starchild there to do — embrace humanity in the spirit of Nietzschean joy? Will he sing Ode to Joy or Dies Irae? Is he there to fulfill or destroy? Whatever it is, Kubrick offers no visual answers other than musical clues in Richard Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra “Sunrise” prelude. Madness and death is just as likely to follow as world peace and eternal bliss.

Most films find it necessary to end on moral high note with some sort of explanation of benefits. Not Kubrick. That’s a large part of what makes his films so special, so unique, so unnerving. Kubrick does not dictate how his audience should feel. He never fully supports nor condemns. His endings come from our anti-hero’s free will, not a moral code. His characters move in a Nietzschean space of cause and effect and rarely think about consequences.

5. Sigmund Schlomo Freud and 6. Carl Gustav Jung

Sexual Repression and Duality

Freud and Jung are joined at the hip. Many of their theories intertwine — but with some important divergences.

Freud’s career and impact is titanic. He is primarily responsible for the Oedipus complex, and his belief in dreams as wish fulfillments and mechanisms of repression. He also sexualized almost all thought and behavior as an extension of libido and, most importantly in relation to Kubrick’s films, postulated the theory of the death dive — neurotic guilt which leads to a pathway of self-destruction. This is the opposite counterpart to Eros, which is life-affirming.

Jung, a peer, a friend, a co-worker and consultant to Freud, was much more of a Renaissance man. He wrote prolifically on a variety of subjects, not just psychiatry, on subjects that included archeology, literature, and religion. He theorized many concepts currently in use today. He did not sexualize activity, repressed or otherwise, as much (or not at all) as Freud. He is known primarily for individuation — the ability to incorporate opposites while still maintaining the self.

Almost all of Kubrick’s anti-heroes exhibit large parts of one or both of these philosophies. Some, like Full Metal Jacket, make direct reference to Jung. Indeed, the entire film is structured as polar opposites. Dr. Strangelove, on the other hand, is the poster child of Freudian symbolism.

Less so The Shining but not by much. Dr. Strangelove trumpets its twisted, repressed sexuality from the opening scene to the last orgiastic release. There is not a scene, line of dialog, or character name that does not have some kind of scatological, sexual reference to the libido or lack of it.

7. Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm (Brothers Grimm)

Fairy Tales

Who doesn’t like a good fairy tale? Stanley Kubrick certainly does, that’s for sure. Not only did Kubrick like fairy tales, he embraced them.

The Brothers Grim were two highly educated German academics who loved language and their Germanic culture. They collected, codified, wrote and published old folklore stories in an effort to preserve forgotten parts of their oral and sometimes-written story-telling heritage. It is important to note that the Brothers often expanded and/or embellished what they found or heard, while still trying to stay close to the source material.

Aschenputtel (Cinderella), Hänsel und Gretel, Dornröschen (Sleeping Beauty), Schneewittchen (Snow White), amongst many, many others, are just some of the hundreds of stories that emerged from undeveloped or rural regions in Germany. They proved immediately and immensely popular.

As time went on, other cultures found their works violent, cruel, and foreboding — hardly the stuff one would want their child to read. Strictly speaking, the stories were never meant for children, but sometimes the Brothers would simplify or tone down the sexual imagery or violent undertones. Other times they would not.

As much as possible, they respected and honored the Germanic culture from which most of these stories emanated and, despite the atrocities — the cannibalism, mothers abandoning their daughters, fathers hating their sons — thought full disclosure better for German heritage and better for their readers. Germans were never one for hiding behind a whitewashed past.

What did Kubrick learn from the Brothers Grimm? He learned that resolutions aren’t always happy. Someone almost always dies. The Blue Fairy doesn’t exist. Roads are for journeys not destinations. A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, and Eyes Wide Shut are three films that most closely emulate a Grimmsian fairy tale. Even 2001: A Space Odyssey, in a broader, more redefining sense, is the ultimate fairy tale.

Each of the four films exhibits solid characteristics — There is life, there is conflict, there is death, there is resolution (not always a happy one), and there is rebirth. If anything, Grimmsian fairy tales demonstrate a universe full of consequencialism — if one decides to run away from home, no one can help you and you can’t always predict the outcome.

Dax’s knightly efforts in Paths of Glory still leads to an execution. Bowman murders his “parent” and abandons his home and, after a long life (in a cage?), he becomes redeemed and reborn as a Nietzschean “Superman” — good for him, bad for the rest of the 8 billion souls on Earth.

Alex’s libidinous actions and free will exposes a clear social dilemma and double-standard, but he still gets the sex in the end because of his sufferings and father-figures who want to do good by their “sons” and abandon morals on the grounds of principal (and votes!), which begs the age-old question — which is worse, the disease or the cure?

Jack Torrance finds freedom amongst the hotel ghosts but loses his soul in the process and is doomed to a Sisyphusian nightmare of endless repetition — “…you’ve always been the caretaker, Mr. Torrance.” Dr. Harford tries to be a man — in effect running away from home — only to find out “mother’ (his wife) was right all along.

Naturally, Kubrick twists the world of fairy tales on its head, and freely combines genres and influences to craft his stories in unique retellings.

8. Eugene Berthold Friedrich Brecht (Bertolt Brecht) and 9. Antoine Marie Joseph Artaud (Antonin Artaud)

Verfremidungseffekt (Distancing Effect) and Theatre of Cruelty

When it comes to Kubrick’s confrontational, cinematic style, look no further than Brecht and Artaud. Many of his films exhibit theatrical characteristic borrowed from those to titans and originators of the theatre.

Brecht — German-born from Augsburg — proposed a play should not allow the theater-goer to get emotionally involved but somehow view the proceedings rationally. The only way to accomplish that was to consistently remind the audience through a variety of means that they are observers, not participants. This is known as the Brechtian Distancing device.

Some of the techniques include an actor addressing the audience directly, lighting — bad, harsh or otherwise, perhaps even pointed at the audience, songs that interrupted or against the action, misdirection, title cards, someone speaking stage directions out loud and so on. How many of these techniques did Kubrick employ cinematically? All of them! Narration, title cards, harsh or unusual lighting, contrapuntal music, dynamic cuts, loud bangs or chords after long periods of silence — all of these found form and function in a Kubrick film.

Artaud — a Frenchman from Marseille — on the other hand, seemed to be a bit more esoteric in his thinking. He felt, like Brecht, that theater had become too staid and secure. He advocated extreme measures that subverted the text of the play — that maybe even involved the audience directly — to create a type of symbiotic relationship between the two that shattered the false reality of the production.

Cruelty did not mean actual pain or violence, except that which is done to the play (not the playwright!) itself — a violence of ideas, thoughts, emotions, connections, resolutions — anything necessary to shock ones preconceptions into different modes of comprehension.

Artaud wanted to remove words altogether and make a kind of visual play made up entirely of motion in an extremely codified, ritualized way that somehow attained spiritual awakening amongst its participants, which could, if so moved, include theater goers as well as actors. This was very forward thinking stuff!

Kubrick (at least in his films), like Artaud, was a nihilist and fully embraced many Artaudian concepts — especially in his dystopian trilogy of Dr. Strangelove, 2001, and A Clockwork Orange.

10. Wilhelm Richard Wagner

Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art)

Stanley Kubrick, as far as I know, never listened to opera much less Richard Wagner. Perhaps he should have. The two geniuses — the supreme titans of their craft — share a number of striking similarities that bears witness to a pattern of consistency amongst the movers and shakers of art or industry.

Wagner, like most of Kubrick’s indirect influencers, was German-born, from the city of Leipzig, Saxony. His paternity is in question. Carl Friedrich Wagner, a Leipzig police chief, first raised Wagner. There is evidence to suggest that Wagner may have been sired by actor and playwright Ludwig Geyer, with whom Wagner’s mother, Johanna Rosine, had an affair. Geyer was also Jewish. Until age 14, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer.

Kubrick, like Wagner, was a late bloomer who showed little aptitude for what was to come.

Kubrick, like Wagner, struggled with his early works before finding his artistic “voice.”

Kubrick, like Wagner, once he really got going, produced masterpiece after masterpiece until the end of his life.

Kubrick, like Wagner, controlled every element of every production. Wagner even went so far as to build his own theater that would show only his works – the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth.

Kubrick, like Wagner, wrote all of his scripts (in opera they are called librettos.)

Kubrick, like Wagner, took advantage of the latest technology to help produce his vision.

Kubrick was Jewish. Wagner very well could be!

Kubrick and Wagner both vastly redefined the language of their art.

Kubrick’s films consistently make the Top 10 or Best 100 lists. All of Wager’s 10 operas are never out of repertory.

Both Kubrick and Wagner have fans who are either vehement detractors or irrepressibly loyal that think the sun sets on their respective work. There is little middle ground.

And, most of all, there is no mistaking “A film by Stanley Kubrick” in the same way there is no mistaking a Wagnerian opera. From the first opening shots (Kubrick) or chords (Wagner), we know exactly what we’re in for.

And this brings in the quality of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

Whether by design or accident, as a true auteur in control of all aspects of script, production, and post-production, starting with Paths of Glory, Kubrick made films that contained many similar characteristics. The plot changed but his unique style remained almost intact with few exceptions.

Artists go through several periods, phases of inactivity, or explosions of creativity, but it all comes back down to core concepts, intention, private meaning, and artistic preferences. They fashion a repeatable, cinematic language or visual clue all to their own. Some artists, like Wagner write down their thoughts and processes in great detail that make for fascinating reading.

Others, like Kubrick, expressed their views in interviews only — and sparingly at that — preferring the film to tell the full and only story on and about their craft. All things considered, Kubrick would be mortified at the trollish, information-devouring aspect of the Internet. He would certainly think it is unnecessary to know everything about every artist from working conditions to when they took their tea break.

Conclusion

What fitting conclusions can we draw from Kubrick’s sources?

His roots in Russian film orthodoxy are the easiest to trace, as is his affection for Ophülsian didacticism and camera movement. There are clear examples throughout his career that point directly to those influential artists. But, beyond that, aside from a few interviews, nailing down Kubrick’s epistemology requires a leap of faith more akin to writing a doctoral thesis based on intellectual conjecture than facts.

Kubrick is that inscrutable and largely indecipherable and always open to interpretation despite anyone’s claim to authority, mine included. This came about perhaps by design but probably mostly because he never really lost the shy reticence he demonstrated as a child — we really don’t change that much after all. We adapt, yes, but change little. Why he was that shy with an intellect as acute as his is the $64,000 question.

Perhaps he was bullied for his smarts? Perhaps he just wanted to be like everyone else and repressed his true nature as much as possible. His last big interviews were during the 2001 phase in the late 60s. After the controversy of A Clockwork Orange in the early 70s he pulled back a lot and disappeared behind the walls of his estate.

The fact that the vast majority of his sources are German is of no surprise and cannot be discounted. Philosophical influences are harder to prove, of course. Technique has trackable footprints, whereas theory and philosophy in relation to story and structure leaves only impressions in the nebulae of the mind. I understand the dynamics of filmmaking — often you have happy accidents that have little to do with conscious decisions.

I cannot conclusively prove Kubrick was consciously paying visual homage to literary and philosophical concepts developed by Freud, Jung, Brothers Grimm, Nietzsche, Brecht, Artaud and Wagner any more than I can prove Edward de Vere, the 17th earl of Oxford, was the real Shakespeare even though the preponderance of circumstantial evidence agonistically analyzed suggests “William Shakespeare” was a nom de plume masking the identity of the true author and nothing else.

Likewise, the analysis of style, content, story, structure, and characterization shows that Kubrick had a clear attraction, consciously or not, to many things German — all subject to broad interpretation, of course. He even married a German, for crying out loud.

But let me make an even bigger leap even though it departs slightly from my Teutonic concept (and because it fits so well!) Cabbalist tradition (a body of mystical teachings of rabbinical origin, often based on an esoteric interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures that is distinctly Jewish) teaches that all forms of knowledge flows from within, anchored by the Sefirot and connected by pathways that represent ‘subjective understanding and relationship…when two sphere are connected.’

The strict elegance of Cabbalistic teaching may explain why Kubrick’s characters seem mere ciphers than three-dimensional people. Kubrick, for all his visual flair, has always been a formalist, framing his mise-en-scène in constantly mirrored, iconic arrangements. The Cabbalist ‘tree of life’ is mirrored left and right, anchored by a center spine, the left meaning spiritual love, and the right spiritual will. Divided vertically into three triangular areas, they are represented by spirit, soul, and personality of the divine — a life force.

If most of his characters seem as ciphers, it may be precisely because they are rigidly constructed paradigms of Cabbalistic/Nietzschean tradition. There is no on/off, right/wrong, left/right in the traditional sense. In the Kubrick universe, there are ways of tracing character motivations that makes their elemental natures easier to comprehend and visualize in pure, cinematic forms.

Once we understand that their emotions have no basis in any conventional reality, once we can divorce our preconceptions from common platitudes and the husbandry of directorial averageness. We can raise the level of our involvement from the entertained to the questioning and, once we’ve become active, critical thinkers always questioning, always searching, we have then equalized the playing field and become one with the master.

Genius artists being who they are, sub-consciously gravitate towards certain viewpoints they like and admire and distill what they’ve learned into a visual coherence, bringing form and function and structure to a whole host of ideas and concepts, some quite deliberate and others born from deeper recesses.

While Kubrick films often defy meaning at first, throughout my many articles I’ve tried to present a picture of an intellectual giant who approached his craft on a different plain than anyone else. His didacticism reduced his films into mythic fables and these fables into Nietzschean consciousness. But is Kubrick truly Nietzschean or is it just an infatuation? Who really is the man? The artist?

In Kubrick’s films, there is a definite and articulated inclination to madness, violence, anger, perversion, and domination without offering anything in return — no love, as in Mozart; no light, as in Göngora; no joyful Will in love, as in Santayana. The evil of Will is that you can will anger, vengeance, or malevolent duty, and it becomes a lie that is not necessarily yours. Geniuses are truly great when Will comes from love and detachment (e.g. Mozart, Göngora, Schopenhauer, Santayana), not from determination (e.g. Nietzsche, Picasso).

Killer’s Kiss ends happily, if somewhat unconvincingly, but it was downhill from there. Real love is loving the love in others, the ideas they have, their potentialities towards their own perfection. Will in domination, power and energy, as in Nietzsche, is barbaric — and Santayana and Virgil show us how painful it can be when applied.

In Kubrick, one finds causality but little love. Redmond Barry loved his son wholeheartedly, that is plainly evident, but he clearly didn’t love himself or even his wife. Did Alice love her husband in Eyes Wide Shut? Did Humbert Humbert love Lolita? Did Sgt. Hartman love his troops? Did Jack Torrance love his ghosts? Did anyone love anyone in 2001?

In real life, Kubrick was, by all accounts, a happy if overly controlling man, surrounded by his numerous cats, dogs, and other animals, not to mention his large family unit ensconced in a large, idyllic country estate. Was it always paradise? No. Family units by their very nature are not always harmonious.

But it’s still hard to reconcile the private side versus the creative side. In filmmaking, he lorded over his domain with feline precision and Nietzschean temperament while offering little in return. He is truly an agnostic filmmaker who left a loyal audience to fend for themselves and search, often in vain, for nuggets of meaning in his vast, gargantuan canvases.

If it sounds like I am trying to find the proverbial “Rosebud” moment to explain everything, I am. In the vast hoard of Kubrick memorabilia unearthed after his death, a sled, unfortunately, wasn’t among them.

Perhaps, in the end, it’s not for me or anyone else to decide. Perhaps it’s better this is left undecided — it gives us more to talk about. What we are left with is Kubrick as mythmaker, Kubrick as sentient, Kubrick as family man and cat lover, Kubrick as iconoclast, Kubrick as intellectual giant, Kubrick as the greatest, most varied filmmaker the world has ever known or had the privilege to see. In the end he was just a man, religiously pursuing his art along a golden highway paved with hubris, wit, intelligence, and courage built in a universe from whose borne no traveler returns.

Every profound thinker is more afraid of being understood than of being misunderstood. The latter may hurt his vanity, but the former his heart, his sympathy, which always says: “Alas, why do you want to have as hard a time as I did?”

– Friedrich Nietzsche, “Beyond Good and Evil.”

Translated by Walter Kaufman

By Mark Krasselt

You must be logged in to post a comment Login