The Beatles’ Revolver was released on 5 August 1966. As the album turns 50,Greg Kot argues that it is the Fab Four’s crowning achievement.

The best Beatles album? The rock historians often point to Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as the moment, in 1967, when rock magically grew up and became a legitimate art form, at least as it was perceived by the mainstream media. Many fans love the sprawl and variety of the self-titled 1968 double album, popularly known as The White Album. In some quarters there’s a fondness for Abbey Road and its side-long suite of mini-songs, and lovers of the Bob Dylan-influenced folk-rock of the mid-‘60s cherish Rubber Soul above all. They all have merit, but none of them is as consistently brilliant and innovative as Revolver.

It does everything Sgt Pepper did, except it did it first and often better. It just wasn’t as well-packaged and marketed. The hype that preceded Sgt Pepper had a lot to do with the leaps in imagination, the studio-as-instrument adventurousness, that flourished on Revolver in half the time: the sessions for the 1966 album spanned two-and-a-half months whereas Sgt Pepper took an unprecedented five months to record.

[vsw id=”38wIuDAq2yg” source=”youtube” width=”465″ height=”384″ autoplay=”yes”]

Where Revolver began tells us a lot about where it ended up. When recording commenced in April 1966, The Beatles dived into the future with Tomorrow Never Knows. John Lennon conjured a sound in his head, and left it up to producer George Martin and a 20-year-old rookie engineer, Geoff Emerick, to figure out how to get it on tape. They succeeded spectacularly.

“He wanted his voice to sound like the Dalai Lama chanting from a hilltop,” Martin later recalled. “Well, I said, ‘It’s a bit expensive going to Tibet. Can we make do with it here?'”

Lennon’s voice was filtered through a Leslie speaker cabinet, which gave it a vibrato effect normally associated with a Hammond keyboard. George Harrison brought Eastern drones to the track by playing a long-necked lute called the tamboura as well as a sitar, and Paul McCartney cooked up backward and vari-speed tape loops, including one that evoked the sound of seagulls. Ringo Starr’s drums were pushed to the foreground in the mix, inverting the typical hierarchy of most rock instrumentation. Ringo’s drums became the lead instrument, a thundering focal point amid the sonic chaos. Lennon’s ‘Tibetan-monk’ vocals urged listeners to “turn off your mind, relax and float downstream.”

‘One peak to the next’

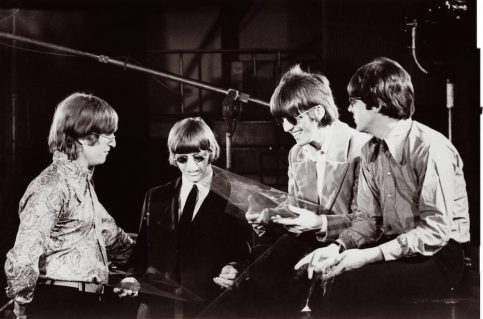

All The Beatles’ previous albums had been rush jobs – their debut was recorded in four hours. But in 1966, the quartet pulled off the road for good to devote themselves to songwriting and record-making. Lennon and McCartney were still closely collaborating and pushing each other to new levels of innovation, and Harrison was emerging as a formidable third songwriter and voice in the band. Now, with the luxury of time to tinker, edit, re-edit and experiment, The Beatles were poised to record a masterpiece.

Tomorrow Never Knows set a high standard for an album that moves from one peak to the next: Harrison’s corrosive guitar lick and McCartney’s commanding counterpoint bassline in Taxman made for one of The Beatles’ toughest-sounding tracks, the brisk strings on Eleanor Rigby presaged the chamber-pop feel and emotional tenor of She’s Leaving Home on Sgt Pepper, and Harrison’s plunge into Eastern mysticism and modalities on Love You To set the stage for the similarly inclined Within You Without You on the later album.

The melancholy beauty of Here, There and Everywhere answered the challenge of Brian Wilson’s Beach Boys masterpiece Pet Sounds, Doctor Robert and And Your Bird Can Sing achieved jingle-jangle guitar-pop perfection, and the horn-fueled Got to Get You Into My Life channeled Motown and Stax soul. Even a relatively lightweight track such as Yellow Submarine presaged the sometimes fanciful, almost child-like wonder of Sgt Pepper tracks such as Lovely Rita.

[vsw id=”SuvMcoZVYUM” source=”youtube” width=”465″ height=”384″ autoplay=”no”]

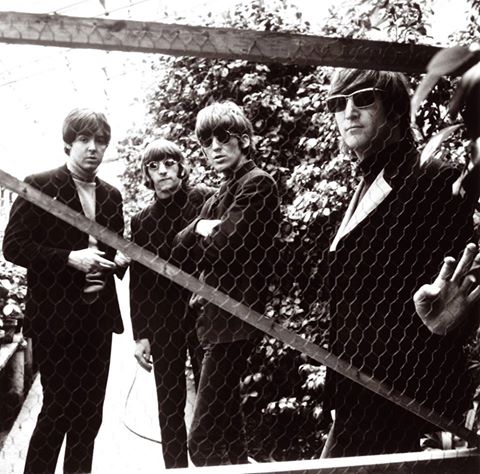

Sgt Pepper proved to be a prettier package, with its elaborate Peter Blake cover art of the satin-suited, newly bearded Beatles among images of cultural icons ranging from Karl Marx to Mae West. The Beatles spent 700 hours in the studio crafting it, but despite its unassailable high points – the staggering A Day in the Life, the acid-rock fantasia Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds – it’s also riddled with the cute and lightweight (When I’m 64, Lovely Rita) and the drab (Within You Without You).

Revolver was preceded by Rubber Soul, recorded in 1965, in which the band had achieved a new level of sophistication in its songwriting. The evocative wordplay in Norwegian Wood and In My Life aspired to the pop poetry of Dylan and Smokey Robinson. Song for song, it matches up well with Revolver, but it’s not nearly as sonically ambitious.

[vsw id=”vefJAtG-ZKI” source=”youtube” width=”465″ height=”384″ autoplay=”no”]

By the time of the 1968 White album, The Beatles were splintering and essentially turned the sessions into a series of solo recordings with the rest of the band members acting as session musicians. It contains some brilliant music – including Lennon’s caustic Happiness is a Warm Gun and McCartney’s civil-rights hymn Blackbird – and at least a side’s worth of filler (sonic collage Revolution 9; juvenile Why Don’t We Do it in the Road?; blues parody Yer Blues; and the music hall pastiche of Honey Pie).

Abbey Road marks The Beatles’ final recording session, and it planted the seeds for progressive rock by stitching together 11 half-finished songs into a sublimely sequenced suite. Its closing line – “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make” – is a career capstone worthy of The Beatles’ legacy. The first side of the album contains Harrison’s finest Beatles moment, Something, and Lennon’s metal precursor She’s So Heavy. It’s the album in The Beatles discography that comes closest to the majesty of Revolver.

Revolver wasn’t always so highly regarded. A few months after it was released, The Beatles began recording Sgt Pepper, an event that was chronicled with great fanfare as the band sequestered themselves in Abbey Road studios. Its magnificence seemed a fait accompli. In contrast, the release of Revolver was overshadowed by Lennon’s infamous and widely misinterpreted ‘more popular than Jesus’ comments. But time has affirmed the enduring worth of Revolver. It now stands as The Beatles’ greatest album.

By Greg Kot

You must be logged in to post a comment Login