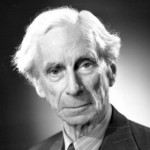

Bertrand Russell on Immortality, Why Religion Exists, and What “The Good Life” Really Means

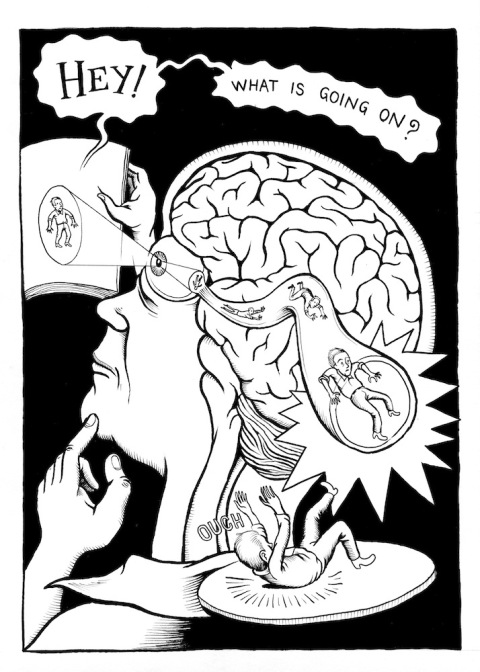

Russell writes in the preface: In human affairs, we can see that there are forces making for happiness, and forces making for misery. We do not know which will prevail, but to act wisely we must be aware of both. One of Russell’s most central points deals with our civilizational allergy to uncertainty, which we try to alleviate in ways that don’t serve the human spirit. Nearly a century before astrophysicist Marcelo Gleiser’s magnificent manifesto for mystery in the age of knowledge — and many decades before “wireless” came to mean what it means today, making the metaphor all the more prescient and apt — Russell writes: It is difficult to imagine anything less interesting or more different from the passionate delights of incomplete discovery. It is like climbing a high mountain and finding nothing at the top except a restaurant where they sell ginger beer, surrounded by fog but equipped with wireless. Long before modern neuroscience even existed, let alone knew what it now knows about why we have the thoughts we do — the subject of an excellent recent episode of the NPR’s Invisibilia — Russell points to the physical origins of what we often perceive as metaphysical reality: What we call our “thoughts” seem to depend upon the organization of tracks in the brain in the same sort of way in which journeys depend upon roads and railways. The energy used in thinking seems to have a chemical origin; for instance, a deficiency of iodine will turn a clever man into an idiot. Mental phenomena seem to be bound up with material structure.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login